The best books we read in 2014

TheWeek.com's staff and writers discuss their favorite books of the year

Americanah, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

Indeed, at its core, Americanah is a love story between Ifemlu and Obinze, her teenage boyfriend — a story that spans continents and languages. Adichie gives us the messy bleeding guts of modern relationships, most strikingly when Ifemlu moves back to Nigeria, showing the hurt that we can inflict upon one another.

Adichie's novel is one that sticks, encompassing so many aspects of the human experience — a modern, realistic, beautiful, painful look at loving and living. --Kerensa Cadenas, writer

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The World Viewed: Reflections on the Ontology of Film, by Stanley Cavell

Wolf in White Van, by John Darnielle

But Wolf in White Van isn't just the best of a Mountain Goats song transferred to a literary medium. It's also a stunningly intense and personal story of a character whose outlook on life has been scarred — physically and emotionally — by a traumatic accident in his teens. What makes Wolf in White Van such an engrossing and stellar novel is Darnielle's visceral way with language, putting us inside the head of his protagonist, Sean Phillips, who connects with people through a mail-in role-playing game. Darnielle favors character development over plot, creating a narrative that's part stream-of-consciousness to allow the mystery of what happened to Sean unfold as we understand him better. --Matt Cohen, writer

All the Light We Cannot See, by Anthony Doerr

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Dirty Love, by Andre Dubus III

Five Came Back, by Mark Harris

Up, Up, and Away, by Jonah Keri

The book is rife with other wonderful tidbits, gleaned from dozens of interviews with everyone from team executives to all-stars. It tracks the expansion team's rise from a doormat stuck on a janky outdoor field to a pennant-winner stuck in a janky domed stadium. Today, the Expos are mostly remembered as a floundering franchise that sold off its players before it, too, got sent packing from Montreal. But Keri passionately exhumes the team's indelible characters and flirtations with glory — including the strike-shortened 1994 season that snuffed out Montreal's best shot at a World Series — revealing how, against all odds, a baseball team became a cherished institution in a hockey-mad city. --Jon Terbush, associate editor

The Boat, by Nam Le

The opening story may seem indulgent at first blush, 26 pages about a writer named Nam who is trying to figure out whether he should draw on his extraordinary experiences as a child refugee from Vietnam. It feels too meta, veering on a polemic about a very specialized genre of "ethnic lit" or "immigrant lit." And then it just rips your guts out. --Michael Brendan Dougherty, senior correspondent

Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage, by Haruki Murakami

The title may be unwieldy, but the book itself certainly isn't. Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki manages to be both elusive and emotionally gripping as it tells the story of the title character, who is dealt a life-altering blow in his early twenties when his four closest friends suddenly and inexplicably announce that they never want to see him or speak with him again. As an adult, Tsukuru Tazaki decides to confront his erstwhile friends about the incident that changed the course of his life, only to discover deeper, stranger mysteries.

Murakami has trafficked in both stark realism (Norwegian Wood) and dizzying surrealism (Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World). But Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki is his purest and most effective marriage of the two styles, resulting in an intricately woven story about the decisions we make, and the unexpected ripple effects that can result. (And yes, there are still plenty of references to jazz and trains.) Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki doesn't have an answer for every question it raises, but it never feels like Murakami is being deliberately coy or lazy. He's simply acknowledging that life will always present new mysteries — and that peace will come in accepting that the answers, when they arrive at all, will be in the hands of others. --Scott Meslow, entertainment editor and film and television critic

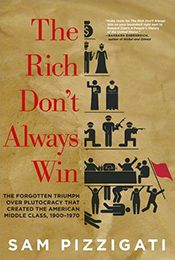

The Rich Don't Always Win, by Sam Pizzigatti

All those things are gone now, of course. The bedrock of America's middle class has been crumbling for decades under the forces of globalization and an energized reactionary assault. America is now more unequal than at any time since the 1920s. But Pizzigatti shows that we've been here before — in the 1920s, like today, both parties were owned wholesale by the rich. Then as now, the rich made a complete dog's breakfast of economic policy. Then as now, there is simply no alternative but serious political mobilization against plutocracy. --Ryan Cooper, national correspondent

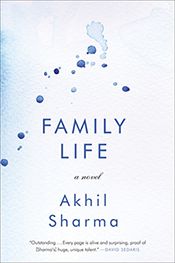

Family Life, by Akhil Sharma

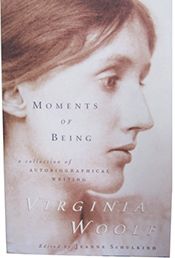

"A Sketch of the Past," by Virginia Woolf

But this isn't really fair to female writers or to readers of either sex, particularly those who have had the pleasure of reading Virginia Woolf's proto-Knausgaardian project "A Sketch of the Past." Like My Struggle, it runs away from any attempt at structure — "[a]nd thus as I dribble on, purposely letting my mind flow" — to go straight to the nitty gritty of existence. Readers will be treated to her first impressions as an infant at her family's summer home at St Ives; memories of her beautiful and beloved mother Julia Stephen; and "an incongruous miscellaneous catalogue" of events and observations, which act as "little corks that mark a sunken net." Most famously, she dwells on what she calls "moments of being," sublime encounters with reality that reveal a pattern "hidden behind the cotton wool of everyday life." It is a slight book, and an unfinished one at that (Woolf would commit suicide four months after the last entry), but it was the closest thing to life that I read this year. --Ryu Spaeth, deputy editor

Create an account with the same email registered to your subscription to unlock access.

-

Today's political cartoons - April 13, 2024

Today's political cartoons - April 13, 2024Cartoons Saturday's cartoons - moderate MAGA, automotive politics, and more

By The Week US Published

-

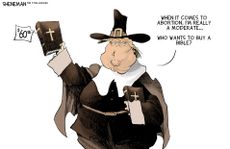

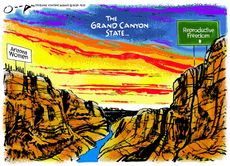

5 Grand Canyon-size cartoons on the Arizona abortion ruling

5 Grand Canyon-size cartoons on the Arizona abortion rulingCartoons Artists take on a chasm in reproductive freedom, the dangers of an abortion ban, and more

By The Week US Published

-

Crossword: April 13, 2024

Crossword: April 13, 2024The Week's daily crossword

By The Week Staff Published