Cancer: Into the wild darkness

In nature, death is not a defeat. But that's a hard comfort as I confront my own.

For 26 Septembers, I've hiked up streams littered with corpses of dying humpbacked salmon. It is nothing new, nothing surprising, not the stench, not the gore, not the thrashing of black humpies plowing past their dead brethren to spawn and die. It is familiar; still, it is terrible and wild. Winged and furred predators gather at the mouths of streams to pounce, pluck, tear, rip, and plunder the living, dying hordes.

This September, it is just as terrible and wild as ever, but I gather in the scene with different eyes, the eyes of someone whose own demise is no longer an abstraction, the eyes of someone who has experienced the tears, rips, and plunder of cancer treatment. In spring, I learned my breast cancer had come back, had metastasized to the pleura of my right lung. Metastatic breast cancer is incurable. Through its prism I now see this world.

I'm not a salmon biologist. I don't hike salmon streams as part of my job. I hike up streams and bear trails and muskegs and mountains for pleasure. The work my husband, Craig, and I do each field season in Prince William Sound is sedentary. We study whales. For weeks at a stretch, we live on a 34-foot boat far from any town, often out of cellphone and Internet range. We sit for hours on the flying bridge with binoculars or a camera pressed to our eyes.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Periodically, we climb down the ladder and walk a few paces to the cabin to retrieve the orca or humpback catalogue, to drop the hydrophone, or to grab fresh batteries, mugs of hot soup or tea, or granola bars. We climb back up. We get wet; we get cold; we get bored; sometimes we even get sunburned. We eat, sleep, and work on the boat. Hikes are our sanity, our maintenance. We hike because we love this rainy, lush, turbulent, breathing, expiring, windy place as much as we love our work with whales.

Normally, September is the beginning of the end of our field season, which starts most years in April or May. But for me, this year it's just the beginning, and conversely, like everything else in my life since I learned cancer had come back, it's tinged with the prescience of ending. The median survival for a person with metastatic breast cancer is 26 months. Some people live much longer. Will this be my last field season? Will the chemo drug I'm taking subdue the cancer into a long-term remission? Will I be well enough to work on the boat next summer? Will I be alive?

A summer of tests and procedures and doctor appointments kept me off the boat until now. A surgery and six-day hospitalization in early August to prevent fluid from building up in my pleural space taught me that certain experiences cut us off entirely from nature — or seem to; I know that as long as we inhabit bodies of flesh, blood, and bone, we are wholly inside nature. But under medical duress, we forget this. Flesh, blood, and bone notwithstanding, a body hooked by way of tubes to suction devices, by way of an IV to a synthetic morphine pump, forgets its organic, animal self.

In the hospital, I learned to fear something more than death: existence dependent upon technology, machines, sterile procedures, hoses, pumps, chemicals easing one kind of pain only to feed a psychic other. Existence apart from dirt, mud, muck, wind gust, crow caw, fishy orca breath, bog musk, deer track, rain squall, bear scat. The whole ordeal was a necessary palliation, a stint of suffering to grant me long-term physical freedom. And yet it smacked of the way people too often spend their last days alive, and it really scared me.

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Ultimately, what I faced those hospital nights, what I face every day, is death impending — the other side, the passing over into, the big unknown — what poet Harold Brodkey called his "wild darkness," what poet Christian Wiman calls his "bright abyss." Death may be the wildest thing of all, the least tamed or known phenomenon our consciousness has to reckon with. I don't understand how to meet it, not yet — maybe never.

Can I take comfort in the countless births and deaths this earth enacts each moment, the jellyfish, the barnacles, the orcas, the salmon, the fungi, the trees, much less the humans? I woke this morning to the screech of gulls at the stream mouth. We'd anchored in Sleepy Bay for the night, a cove wide open to the strait where we often find orcas. The humpbacked salmon — millions returned this summer, a record run — are all up the creeks now.

Before starting our daily search, Craig and I kayaked to shore. As we approached, I watched the gulls, dozens of them, launching from the sloping beach where the stream branches into rivulets and pours into the bay. They wheeled and dipped over our heads, then quickly settled again to their grim task, plucking at faded salmon carcasses scattered all over the stones.

The stench of a salmon stream in September is a cloying muck of rot, waste, ammonia. This is in-your-face death, death without palliation or mercy or intervention. At the same time, it is enlivening, feeding energy to gulls, bears, river otters, eagles, and the invisible decomposers who break the carcasses down to just bones and scales, which winter then erases. In spring, I kneel and drink from the same stream's clear cold water, or plunge my head into it. It is snowmelt and rain filtered through alpine tundra, avalanche chute, muskeg, fen, and bog. It is water newly born, fresh, alive, and oxygenated, rushing over clean stones, numbing my skin.

After we dragged the kayaks above the tide line, Craig wandered down the beach to retrieve a five-gallon bucket he'd spotted and left me alone at the stream mouth. Normally, I am nervous about bears. But this time, I walked up the stream toward the woods without singing or calling out. I stood on the bank and watched the birth-death spectacle. When Craig joined me I uttered this platitude: "We have separated ourselves so much from nature."

I didn't say what I really meant. I rarely do these days. I fear most people, even those who love me best, would think me morbid if they could read my thoughts. Sometimes, with Craig, I imagine he hears the words beneath my words, knows my mind, and then silence seems the best form of conversation. What I really meant was that despite the lack of palliation or mercy or intervention, I envied those salmon their raw deaths, not for a moment separated from nature, not even when dragged from their element by a bear.

I know, I know. Dying of cancer in a bog would not look or sound pretty or peaceful. Hidden from view in this dream scene is the suffering, is the agony. Is the needle, and the morphine pump, unavailable to the salmon, eyeless, its wordless mouth opening and closing, body swaying in its tattered, whitening skin.

I don't by any means think constantly about dying. My reality is dual: one foot firmly in the living stream, the other on the gory bank. Life has become vivid and immediate these last months. No years of Buddhist meditation got me to this place, just words on the phone: The cells were malignant. Later that day, after the crying, after the sitting mutely on the living room couch and staring out the window, Craig and I hauled a quilt into the backyard and lay down on the ground at the edge of the woods. We curled up, listening to wind in the birch leaves, the frenetic din of territorial birds, staking their claims. Spring sprung on while we dozed off. Staying in the present moment isn't difficult when the alternative is dire: useless imaginings of what might or might not come to pass.

Craig and I hiked up the creek to where a path led into the forest, where blueberry bushes grew along the margins of bog. It wasn't a pleasant way to get there. The rocks were slick with decay, the water rushing and tea-colored from weeks of rain. The stink was thick as syrup around us, unrelenting. I stepped around half-consumed corpses, curled and sloughing skin, over eyeless heads, headless flanks, brainless skulls, pearly backbones stripped of meat. As I crossed the creek, live humpies thumped my ankles, then battered themselves against the rocks to get away. In their singular drive to spawn, they plowed right through eddies of bleached-out dead, as if that fate were not meant for them.

Pico Iyer describes the charnel grounds along the banks of the Ganges in this way: "Spirituality in Varanasi lies precisely in the poverty and sickness and death that it weaves into its unending tapestry: A place of holiness, it says, is not apart from the world, in a Shangri-La of calm, but a place where purity and filth, anarchy and ritual, unquenchable vitality and the constant imminence of death all flow together." If there is spirituality in nature, it is in the sublime purity of wild roses and wild mushrooms in mossy woods and the vitality of deer nibbling kelp on the beach and the violet light of an oncoming storm and, equally, in the anarchy and filth of the spawning grounds, in the undoctored real of the ever-dying world.

Facing death in a death-phobic culture is lonely. But in wild places like Prince William Sound or the woods and sloughs behind my house, it is different. The salmon dying in their stream tell me I am not alone. The evidence is everywhere: in the skull of an immature eagle I found in the woods; in the bones of a moose in the gully below my house; in the corpse of a wasp on the windowsill; in the fall of a birch leaf from its branch. These things tell me death is true, right, graceful; not tragic, not failure, not defeat.

We have no dominion over what the world will do to us, all of us. What the earth will make of our tinkering and abuse can be modeled by computers but is, in the end, beyond our reckoning, our science. Nature is not simply done to. Nature responds. Nature talks back. Nature is willful. We have no dominion over the wild darkness that surrounds us. It is everywhere, under our feet, in the air we breathe, but we know nothing of it. We know more about the universe and the mind of an octopus than we do about death's true nature. Only that it is terrible and inescapable, and it is wild.

Death is nature. Nature is far from over. In the end, the gore at the creek comforts more than it appalls. In the end — I must believe it — just like a salmon, I will know how to die, and though I die, though I lose my life, nature wins. Nature endures. It is strange, and it is hard, but it's comfort, and I'll take it.

This story originally appeared in Orion magazine (www.orionmagazine.org).

-

The Democrats: time for wholesale reform?

The Democrats: time for wholesale reform?Talking Point In the 'wreckage' of the election, the party must decide how to rebuild

By The Week UK Published

-

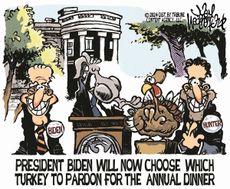

5 deliciously funny cartoons about turkeys

5 deliciously funny cartoons about turkeysCartoons Artists take on pardons, executions, and more

By The Week US Published

-

Crossword: November 23, 2024

Crossword: November 23, 2024The Week's daily crossword puzzle

By The Week Staff Published