The next president will have a terrible relationship with the press

No matter if Trump or Hillary wins, it's going to be hostile

In less than three years as president of the United States, John F. Kennedy gave 64 press conferences, for an average of one every 16 days. While some prior presidents had given more, they were usually off the record, with the president chatting amiably with the men of the White House press corps behind closed doors and often dictating which quotes could be used and which couldn't. Kennedy ordered that his be televised, setting the template for what we know today as the presidential press conference: the leader standing behind a podium while cameras click away and reporters toss their best zingers at him, all for the benefit of an audience watching at home.

But the relationship between the press and the president in those days was much more cooperative than it is now, as evidenced by the fact that reporters declined to write stories about Kennedy's alleged infidelities. And this year, we have two candidates who share an unusual hostility toward the press. Though they talk about it in very different ways, neither one thinks they get treated fairly, and that has some serious implications for what the next presidency will be like.

Let's start with Hillary Clinton.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

She hasn't given a press conference since December, and journalists are, if chagrined, not surprised that she's holding them at arm's length. Clinton's distrust of the media is deeply felt and born of long experience. Ever since the press drove itself into a frenzy over Whitewater in 1992 — in which neither Bill nor Hillary Clinton actually did anything wrong, other than lose some money — one faux-"scandal" after another has followed the same pattern, in which the press breathlessly picked up on some new allegation pushed by Republicans, giving it blanket coverage before it eventually peters out into nothing. In reaction, Clinton became focused on secrecy and withholding information so as not to provide fodder for further such stories. Reporters, in response, became more and more interested in finding out what she wanted to keep from them, and the cycle has never stopped.

The result is what some people refer to as the "Clinton Rules," a special set of standards that apply only to them. Perhaps the best explanation comes in this piece from Vox's Jonathan Allen; they include, "Every allegation, no matter how ludicrous, is believable until it can be proven completely and utterly false. And even then, it keeps a life of its own in the conservative media world," and "The media assumes that Clinton is acting in bad faith until there's hard evidence otherwise."

Indeed, the most plausible explanation for why Clinton set up a private email system when she was secretary of state — a decision which now has to stand as one of the most spectacular political screw-ups in American history — is that she knew that she'd be sued, investigated, and FOIA'ed within an inch of her life, and she wanted to shield her private communication from that spotlight. It wasn't because she had an international criminal conspiracy to conceal, but because she thought that no matter what, everything she did would be treated as though it was a scandal. And we've seen the result: a validation of both the press' belief that Clinton is always hiding something, and Clinton's belief that when it comes to her, they'll always make a mountain out of a molehill.

So what does that portend for a Clinton presidency? It's difficult to see how this cycle is going to be broken, especially when reporters will always want more openness and more access than they've been granted. Every White House has things it wants to keep away from prying eyes (sometimes legitimately so, sometimes not), and that inevitably leads to frustration. In Clinton's case, the likely result will be a lot of stories asking what the administration is hiding, which will only reinforce Clinton's belief that reporters are out to get her.

There's also no reason to think that the endless cycle of scandal coverage will abate, whether there are real scandals to discuss or not. Republicans are well aware that there's an endless appetite in the press for Clinton scandal stories, and they're eager to feed that appetite (in case you were wondering why there were eight separate investigations into Benghazi). Barack Obama's administration has been remarkably free of scandal, and the few things the Republicans tried to pin on it (like Solyndra or the IRS) didn't stick. The most important reason was that the facts just couldn't support it; there was no corruption or malfeasance to be found, no matter how hard they looked. It was also critical that none of those controversies got anywhere near the president himself, a factor that will always elevate a scandal. But it's also easy to argue that if the same events had occurred with a Clinton in the White House, they would have had a much longer media shelf life, since so many reporters bring a baseline assumption of corruption to anything having to do with the Clintons.

And what about Donald Trump?

His relationship with the press is much more extreme than Clinton's, in both directions. On one hand, while Clinton is always friendly in person, Trump is more plainly abusive toward journalists than any presidential candidate in modern history. He regularly denies news organizations credentials for his events when their reporting displeases him. And at every one of his rallies, he points to the reporters held in a pen and tells the audience that they're the most dishonest, disgusting, disgraceful people in the world. He knows full well what happens next: His fans turn around to give reporters the finger and shout insults and threats at them. On at least one occasion, a reporter required a Secret Service escort out of the arena because Trump had singled her out for his invective. A Trump press conference is likely to be filled with insults at intemperate questions ("You're a sleaze," he said to one reporter who asked him a question he didn't like).

Yet at the same time, Trump has spent decades cultivating reporters, and can be quite generous in granting interviews; for instance, he spent 20 hours with reporters from The Washington Post writing a biography of him. They captured the contradiction when they described how "throughout the interviews, he was alternately enthusiastic ('Let's keep going — this is a lot of fun,' he said during one of our sessions, rebuffing his secretary's effort to bring the meeting to a close) and sternly skeptical, repeatedly telling us about the 'lowlife reporters' who had written books about him through the decades and about the legal actions he had contemplated or taken against those authors." He's desperate for attention, and enraged when it doesn't show him in a heroic light.

Just as is true of pretty much everyone else he encounters, in Trump's eyes a reporter is either a terrific, top-notch person or the worst human being in the world, depending on whether he liked the last thing the reporter wrote about him. And in a Trump White House, his momentary whims would likely be passed down through his aides. Write a skeptical story about President Trump, and you could find yourself insulted publicly and frozen out, perhaps even have your credentials to cover the White House revoked. Just as is true of the reporters covering Trump now, that wouldn't stop them — even those barred from attending his events have found ways to report on his campaign, often producing exemplary stories.

But no matter what, the next president is likely to have a hostile relationship with the men and women whose job it is to tell the American public what the administration is doing. That's going to make both the president's and the reporters' jobs more difficult. In the end, that won't be good for anybody.

Create an account with the same email registered to your subscription to unlock access.

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Paul Waldman is a senior writer with The American Prospect magazine and a blogger for The Washington Post. His writing has appeared in dozens of newspapers, magazines, and web sites, and he is the author or co-author of four books on media and politics.

-

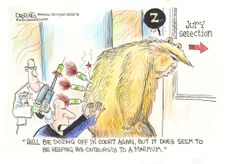

5 sleeper hit cartoons about Trump's struggles to stay awake in court

5 sleeper hit cartoons about Trump's struggles to stay awake in courtCartoons Artists take on courtroom tranquility, war on wokeness, and more

By The Week US Published

-

The true story of Feud: Capote vs. The Swans

The true story of Feud: Capote vs. The SwansIn depth The writer's fall from grace with his high-flying socialite friends in 1960s Manhattan is captured in a new Disney+ series

By Adrienne Wyper, The Week UK Published

-

Scottie Scheffler: victory for the 'pre-eminent golfer of this era'

Scottie Scheffler: victory for the 'pre-eminent golfer of this era'Why Everyone's Talking About Masters victory is Scheffler's second in three years

By The Week Staff Published

-

Arizona court reinstates 1864 abortion ban

Arizona court reinstates 1864 abortion banSpeed Read The law makes all abortions illegal in the state except to save the mother's life

By Rafi Schwartz, The Week US Published

-

Trump, billions richer, is selling Bibles

Trump, billions richer, is selling BiblesSpeed Read The former president is hawking a $60 "God Bless the USA Bible"

By Peter Weber, The Week US Published

-

The debate about Biden's age and mental fitness

The debate about Biden's age and mental fitnessIn Depth Some critics argue Biden is too old to run again. Does the argument have merit?

By Grayson Quay Published

-

How would a second Trump presidency affect Britain?

How would a second Trump presidency affect Britain?Today's Big Question Re-election of Republican frontrunner could threaten UK security, warns former head of secret service

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK Published

-

'Rwanda plan is less a deterrent and more a bluff'

'Rwanda plan is less a deterrent and more a bluff'Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

By The Week UK Published

-

Henry Kissinger dies aged 100: a complicated legacy?

Henry Kissinger dies aged 100: a complicated legacy?Talking Point Top US diplomat and Nobel Peace Prize winner remembered as both foreign policy genius and war criminal

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK Last updated

-

Trump’s rhetoric: a shift to 'straight-up Nazi talk'

Trump’s rhetoric: a shift to 'straight-up Nazi talk'Why everyone's talking about Would-be president's sinister language is backed by an incendiary policy agenda, say commentators

By The Week UK Published

-

More covfefe: is the world ready for a second Donald Trump presidency?

More covfefe: is the world ready for a second Donald Trump presidency?Today's Big Question Republican's re-election would be a 'nightmare' scenario for Europe, Ukraine and the West

By Sorcha Bradley, The Week UK Published