How right-wing insurgencies win

Our democratic institutions remain vulnerable to the machinations of populist outsiders

Political reality can change with alacrity — and radically so.

Consider what happened in Germany between 1928 and 1933. In the elections of May 20, 1928, the National Socialist Party received a miniscule 2.6 percent of the popular vote, winning just 12 out of 491 seats in the Reichstag. By March 5, 1933, the date of the fifth national election in as many years, the Nazis' share of the vote had swelled to 43.9 percent, giving the party 288 seats out of 647.

The single most salient variable in the changing electoral fortunes of fascism in Germany was the stock market crash of 1929, which delegitimized the parties of the center and boosted support for the ideological extremes. But the eventual triumph of the far right was a product of the way that economic shock interacted with the parliamentary system of the Weimar Republic itself.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Of course, most of today's right-wing populists are not Nazis. But we can still learn a lot from Germany's past as we see these right-wing insurgents making gains in countries throughout the West in part by exploiting vulnerabilities in representative institutions.

The ongoing situation in Germany serves as an especially vivid illustration. Again, the far-right upstart party Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) isn't an explicit successor to the National Socialists, and its leader Jörg Meuthen isn't Adolf Hitler. Yet the unfolding situation in the country will be familiar to anyone who's studied the breakdown of parliamentary governments in other times and places.

AfD was founded in 2013 to oppose the way German Chancellor Angela Merkel had handled the eurozone crisis. In the 2013 federal elections, the party won a paltry 4.7 percent of the vote, falling just short of the 5 percent threshold required to win seats in parliament (the Bundestag). But just four years later, after a popular backlash to Merkel's policy of admitting to the country over a million Syrian refugees, the AfD nearly tripled its showing, winning 12.6 percent of the vote and 94 seats in the Bundestag.

That was an ominous development — but not nearly as ominous as what's happened since. On Sunday, Merkel announced that month-long negotiations with the socially liberal Green Party and the pro-business Liberal Party (FDP) over forming a government with Merkel's own center-right Christian Democratic Union (CDU) had collapsed. The cause? The chairman of the FDP (Christian Lindner) had outflanked Merkel on the right and refused to join a coalition that would support a policy of allowing relatives of refugees to join their loved ones in Germany.

That leaves Merkel to choose among a handful of bad options. She can try to persuade the center-left Social Democratic Party (SPD) to join with the CDU in the same "grand coalition" that governed the country until the recent election. The problem is that the SPD's electoral fortunes (like those of many other center-left parties across Europe) are in steep decline, and the party's leadership thinks forming another government with the CDU would hasten its collapse into irrelevancy. Assuming the SPD won't play ball, Merkel's CDU could also try to govern alone, without a majority. But that would leave the government extremely weak.

The one remaining option is to call for another election, hoping the CDU's fortunes improve the next time around. But that's unlikely. The primary reason why Merkel has had such difficulty forming a government is that the mainstream parties refuse to permit the AfD to participate in a governing coalition. That leaves fewer seats available to form a government. But the very failure to form a government gives ammunition to the AfD in its crusade against the establishment parties. If the AfD is given another chance to run against those parties, it may well increase its vote share and thereby make it even more difficult for the mainstream parties to form a government.

With each round of voting, the crisis will worsen. And as the crisis worsens, the power of the insurgents will grow. Eventually, the upstart, far-right party could end up winning enough seats that forming a government without its participation would be nearly impossible. (Something like this dynamic is how Hitler became German chancellor in 1933, and how far-right populists have come to power in Austria and the Czech Republic over the past two months.)

In the United States, which like many presidential systems awards 100 percent of the power to whichever candidate/party wins a plurality of the votes in a given district, insurgents need to take a very different approach — winning elections outright. When an insurgency takes the form of a third-party bid, this can be an insurmountable obstacle, since the electoral system strongly disfavors third parties. But when the insurgency takes place within an existing party, as has been happening within the GOP since Donald Trump launched his presidential campaign, things become more unstable and more dangerous, with the insurgency enjoying the structural advantages that nearly always accrue to major-party candidates.

This is especially true in an environment rife with negative partisanship, which convinces members of the party who would normally be inclined toward skepticism of the insurgent to nonetheless vote for him out of a conviction that any candidate from our party, no matter how unconventional, is better than any candidate from their party. (It's this conviction that may well power Alabama Senate candidate Republican Roy Moore to a victory over Democrat Doug Jones, despite the Republican facing numerous credible charges of sexual misconduct, including one case involving a 14-year-old girl).

But sometimes negative partisanship isn't enough to prevail. That's where voter suppression comes in. Building on the counter-majoritarian tendencies of the American political system, which awards outsized power to sparsely populated (Republican-leaning) rural states over densely populated (Democratic-leaning) urban ones, elected officials can actively seek to suppress the vote among populations inclined to support the insurgency's opponents. That's precisely what the Trump administration's bogus voter-fraud commission is aiming to do.

Thomas Brunell, the partisan Republican Trump plans to appoint to the top operational job at the U.S. Census Bureau, may well go even further. As Politico notes in its story on the pending appointment, "The pick would break with the longstanding precedent of choosing a nonpolitical government official as deputy director of the U.S. Census Bureau. The job has typically been held by a career civil servant with a background in statistics.”

But not this time. Brunell, who has argued that competitive elections are bad for the country, could use his position to give a Republican Party transformed by the Trump insurgency an added structural advantage in future American elections by undercounting citizens who tend to vote for Democrats.

Whether it happens through a succession of elections in which insurgents take advantage of the haplessness of centrist parties or through manipulation of the rules to give insurgents an unfair edge in voting, democratic institutions remain vulnerable to the machinations of populist outsiders. What remains to be seen is whether those institutions prove to be more resilient now than they ended up being 80 years ago.

Create an account with the same email registered to your subscription to unlock access.

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.

-

Olive oil: alternatives for the 'liquid gold'

Olive oil: alternatives for the 'liquid gold'The Week Recommends As the price of this store cupboard staple has rocketed, we look at ways to save and other oils to use for cooking

By Adrienne Wyper, The Week UK Published

-

Scotland Yard, Gaza and the politics of policing protests

Scotland Yard, Gaza and the politics of policing protestsTalking Point Met Police accused of 'two-tier policing' by former home secretary as new footage emerges of latest flashpoint

By The Week UK Published

-

'Cure for Trump amnesia might be his NY trial'

'Cure for Trump amnesia might be his NY trial'Today's Newspapers A roundup of the headlines from the US front pages

By The Week Staff Published

-

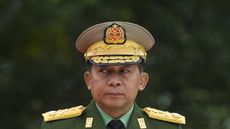

Myanmar: the Spring Revolution and the downfall of the generals

Myanmar: the Spring Revolution and the downfall of the generalsTalking Point An armed protest movement has swept across the country since the elected government of Aung San Suu Kyi was overthrown in 2021

By The Week Staff Published

-

Israel hits Iran with retaliatory airstrike

Israel hits Iran with retaliatory airstrikeSpeed Read The attack comes after Iran's drone and missile barrage last weekend

By Peter Weber, The Week US Published

-

Is there a peaceful way forward for Israel and Iran?

Is there a peaceful way forward for Israel and Iran?Today's Big Question Tehran has initially sought to downplay the latest Israeli missile strike on its territory

By Sorcha Bradley, The Week UK Published

-

Sudan on brink of collapse after a year of war

Sudan on brink of collapse after a year of warSpeed Read 18 million people face famine as the country continues its bloody downward spiral

By Peter Weber, The Week US Published

-

How powerful is Iran?

How powerful is Iran?Today's big question Islamic republic is facing domestic dissent and 'economic peril' but has a vast military, dangerous allies and a nuclear threat

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK Published

-

US, Israel brace for Iran retaliatory strikes

US, Israel brace for Iran retaliatory strikesSpeed Read An Iranian attack on Israel is believed to be imminent

By Peter Weber, The Week US Published

-

How green onions could swing South Korea's election

How green onions could swing South Korea's electionThe Explainer Country's president has fallen foul of the oldest trick in the campaign book, not knowing the price of groceries

By Sorcha Bradley, The Week UK Published

-

Ukraine's battle to save Kharkiv from Putin's drones

Ukraine's battle to save Kharkiv from Putin's dronesThe Explainer Country's second-largest city has been under almost daily attacks since February amid claims Russia wants to make it uninhabitable

By Sorcha Bradley, The Week UK Published