Here's what would need to happen to verify North Korea's denuclearization

The Trump-Kim denuclearization agreement is incredibly vague. That's a huge problem.

"Insulting."

That's what Secretary of State Mike Pompeo called a reporter's question about why scientific terms, like "verification," a mainstay of arms control treaties, weren't included in the joint letter that President Trump and North Korea's Kim Jong Un signed on Tuesday during their summit in Singapore. In the document, North Korea recommits to denuclearization, but the statement itself gives no mention of how, exactly, the denuclearization process would be tracked and ensured.

The absence of such key words, which have come to define a generation of scientific and technical processes designed to ensure that states subject to treaties don't cheat, have generated suspicion among, well, everyone, that what Trump and Kim agreed to is the sum and substance of nothing at all. Nonsense, insists Pompeo. The document signed on Tuesday is just the tip of the iceberg, and it merely covers a vast number of "modalities" — his word — that negotiators between the two countries have already agreed to in principle and want to flesh out before putting them on paper.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

To that end, there are two possibilities. One is that Trump and Kim did not speak using the lingua franca of arms control, and well-meaning, ambitious diplomats will have to push ahead without clear and direct guidance from their respective leaders. The other possibility is that the U.S. hasn't figured out exactly what it needs to verify. South Korea, China, and Japan might want to weigh in, too.

So what does "verification" actually mean? Exactly what you think: If a country declares to the world that it has X amount of Y — be it 10 ballistic missiles or 200 grams of highly enriched uranium — the counter-party to the treaty has to be reasonably certain that the country is not lying. So, they verify.

Verification regimes generally start with a country declaring whatever it is required to declare. Right now, we don't know what North Korea would need to declare — missiles? Weaponization technology? All of its uranium and plutonium stores? Its enrichment sites? Its manufacturing sites? Command and control facilities? Chemical and biological weapons research sites? Some? All?

After declaration, the country would allow for an initial round of intrusive inspections — think scientists with gadgets and sniffers and scopes peering through walls, counting, labeling, affixing things.

Then, the parties to the treaty agree on the terms of how the initial counts can be reverified, and if, for example, the treaty calls on the number of certain widgets to be less year-by-year, how the world will know that this has actually happened. This is the hard part, because a country can hide stuff at will. Facility inspections can be random, but North Korea will claim that its legitimate defense needs are subject to its own controls, so they'll want advance notice for inspections.

If North Korea's weapons technology is advanced, it might want inspectors to use scanning technology that verifies the fission/fusion qualities of a warhead or a stockpile without visual access to the ins and outs of the weapon itself. Conventional ballistic missiles have sophisticated deception devices that North Korea wouldn't want to share — and wouldn't be required to share in a nuclear arms treaty. In the language of arms control treaties, countries should be able to monitor "capacities" without necessarily having access to "designs" — unless the treaty prohibits specific designs.

Countries use spy satellites to track declared convoys of material and weapons. They can use embedded sensors, some of them covert, to track fissile material and radiation. But these mechanisms tend not to provide much in the way of value for arms control inspectors. What does work, however, is precisely what Kim probably does not want: lots of intrusive inspections, followed by persistent overflights of suspected sites, accompanied by drones that loiter over those sites for long periods of time.

A complete denuclearization treaty will require that monitors be able to watch the destruction of the nuclear stuff in the open. If it bears any similarity to the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty between the U.S. and the USSR, it would also ban North Korea from encrypting data about any conventional ballistic missile tests it conducts, and require "portal monitoring" of declared facilities, data exchanges, and more.

No verification procedure can preclude cheating and counter-measures. So it makes sense that Pompeo is cagey on the specifics. But verification must happen. It is the most critical part of any path toward a nuke-free Korean Peninsula. Starting out on that path without a clear and outright mention of how verification will be achieved is foolish.

Create an account with the same email registered to your subscription to unlock access.

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Marc Ambinder is TheWeek.com's editor-at-large. He is the author, with D.B. Grady, of The Command and Deep State: Inside the Government Secrecy Industry. Marc is also a contributing editor for The Atlantic and GQ. Formerly, he served as White House correspondent for National Journal, chief political consultant for CBS News, and politics editor at The Atlantic. Marc is a 2001 graduate of Harvard. He is married to Michael Park, a corporate strategy consultant, and lives in Los Angeles.

-

'Voters know Biden and Trump all too well'

'Voters know Biden and Trump all too well'Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

By Harold Maass, The Week US Published

-

Is the Gaza war tearing US university campuses apart?

Is the Gaza war tearing US university campuses apart?Today's Big Question Protests at Columbia University, other institutions, pit free speech against student safety

By Joel Mathis, The Week US Published

-

DOJ settles with Nassar victims for $138M

DOJ settles with Nassar victims for $138MSpeed Read The settlement includes 139 sexual abuse victims of the former USA Gymnastics doctor

By Justin Klawans, The Week US Published

-

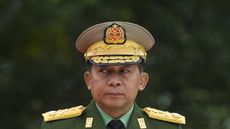

Myanmar: the Spring Revolution and the downfall of the generals

Myanmar: the Spring Revolution and the downfall of the generalsTalking Point An armed protest movement has swept across the country since the elected government of Aung San Suu Kyi was overthrown in 2021

By The Week Staff Published

-

Israel hits Iran with retaliatory airstrike

Israel hits Iran with retaliatory airstrikeSpeed Read The attack comes after Iran's drone and missile barrage last weekend

By Peter Weber, The Week US Published

-

Is there a peaceful way forward for Israel and Iran?

Is there a peaceful way forward for Israel and Iran?Today's Big Question Tehran has initially sought to downplay the latest Israeli missile strike on its territory

By Sorcha Bradley, The Week UK Published

-

Sudan on brink of collapse after a year of war

Sudan on brink of collapse after a year of warSpeed Read 18 million people face famine as the country continues its bloody downward spiral

By Peter Weber, The Week US Published

-

How powerful is Iran?

How powerful is Iran?Today's big question Islamic republic is facing domestic dissent and 'economic peril' but has a vast military, dangerous allies and a nuclear threat

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK Published

-

US, Israel brace for Iran retaliatory strikes

US, Israel brace for Iran retaliatory strikesSpeed Read An Iranian attack on Israel is believed to be imminent

By Peter Weber, The Week US Published

-

How green onions could swing South Korea's election

How green onions could swing South Korea's electionThe Explainer Country's president has fallen foul of the oldest trick in the campaign book, not knowing the price of groceries

By Sorcha Bradley, The Week UK Published

-

Ukraine's battle to save Kharkiv from Putin's drones

Ukraine's battle to save Kharkiv from Putin's dronesThe Explainer Country's second-largest city has been under almost daily attacks since February amid claims Russia wants to make it uninhabitable

By Sorcha Bradley, The Week UK Published