Hey, American businesses: Stop being so shamefully miserly with paid sick and family leave

We've run this experiment at the state level, and the benefits to businesses render the costs moot

President Obama wants paid sick and family leave for American workers. He made that abundantly clear in his State of the Union speech, and in a number of recent policy proposals.

The moral argument for these policies is almost too obvious to state. But the economic case is straightforward, too: If a person is faced with caring for a newborn or a sick elder or other family member, and paid leave isn't available, they have to weigh the importance of giving their family member their full attention against leaving their job, the loss of income and all the financial distress that entails, and the difficulties and uncertainties in eventually finding new employment. Meanwhile, employers must go through the time and expense of finding a new hire and training them for the role. Conversely, people who decide to stay at their jobs will likely be less productive, because they're trying to juggle their work with their suddenly more demanding obligations at home.

The economic argument for paid sick leave is similar: If employees are able to take time to recover from an illness, they'll be more productive when they are in the office and thus make the business more money. They'll also be far less likely to infect other employees. Whatever costs employers avoid by not having paid sick days, and whatever productivity is gained by employees coming into work when they're ill, is lost to the workers' inability to perform and to the risk of passing on the bug to other employees.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Nonetheless, many Republican lawmakers and business interests, along with other conservative critics, disagree, arguing that robust leave policies would hamper firms' flexibility, reduce wages, and kill jobs. "Americans have great freedom when it comes to work," said Sen. Lamar Alexander (R-Tenn.), the chariman of the Senate's Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee. "They can choose the career they like and negotiate with their employer for the things they need... One more government mandate, however well-intentioned, will only reduce those freedoms."

But the flippant notion that employees can fend for themselves papers over some remarkable class disparities. Plenty of businesses provide paid sick leave on their own, but while at least 80 percent of earners in the top fourth of the income ladder get it, only a third of earners in the bottom fourth do. And only 12 percent of U.S. workers at any income level get paid parental leave. It also begs the question of why federal legislation cannot itself be an arena for negotiations between employers and employees; indeed, the U.S. is pretty much the only advanced country that doesn't nationally mandate paid sick and parental leave, and its law requiring 12 weeks of unpaid leave only covers about two-thirds of workers.

Like a lot of policy disputes in Washington, you can find clarity on these issues by digging into actual real-world examples of how these policies play out. California has had a paid family leave law in place for about a decade, and Connecticut has had paid sick days for several years. And by all accounts, both policies are working out just fine for everyone involved.

Let's look at California. In 2004, the state amended its disability program to provide up to six weeks of paid leave to care for a newborn, an adopted child, or a sick family member, with the pay during leave replacing 55 percent of the previous wage. The program is bankrolled by a payroll tax that falls solely on employees. (The bill in Congress that would provide a similar system at the national level is a bit different — it would be paid for by fees leveled jointly on employers and employees, and would replace wages up to 66 percent of their normal level.)

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Critics in California initially seized on the same gripes we're hearing nationally now. But a survey of the state in 2009 and 2010 — several years after the paid leave policy had been implemented — found that 93 percent of employers reported either no noticeable effect or a positive effect on employee turnover, 88.5 percent reported the same for productivity, and 91 percent reported the same on profitability and performance. The benefits of the program for workers — in terms of income replacement, satisfaction with the leave, and other factors — were particularly striking for Californians in lower-quality jobs.

In Connecticut, meanwhile, a law enacted in 2012 mandates that businesses with 50 or more workers allow their employees to earn up to five days of paid sick leave per year. (The national proposal for paid sick days would work the same way, allowing employees at any firm with 15 or more workers to earn seven paid sick days a year, paid for by the employer.) A 2013 survey found that 47 percent of employers reported no increase in business costs, while another 30 percent reported modest increases of 2 percent or less. A third of businesses reported boosts to company morale. And a year after the program's implementation, well over two-thirds of Connecticut employers said they were "somewhat" or "very" supportive of the program.

So why is it that conservatives and business interests howl about paid and family leave policies before they're enacted, and then mostly accept them — and even grow to like them — once they're put in place?

"People don't really consider what the additional economic benefits are going to be," said Alexandra Mitukiewicz, a research associate at the Washington Center for Equitable Growth. "The fact that it's going to reduce turnover, increase worker productivity, allow workers to maintain more labor force attachment, and increase labor force participation. I think those kinds of hidden benefits and long-term benefits are not really brought into the argument. Even though a handful of research studies have found these benefits."

The complexity of the economy — and all the ways policy interventions can have unforeseen consequences — is usually held up as a reason to avoid interventions like this. But that complexity is also why the "just so" stories about how efforts to make our economy more humane will just kill jobs are so often wrong. Robust sick and family leave is not only the right thing to do for Americans — it has clear economic benefits to employees and employers alike.

And Americans themselves are on board: Massive majorities of voters, including majorities of Republicans, support these policies. There really is no good reason not to adopt them.

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.

-

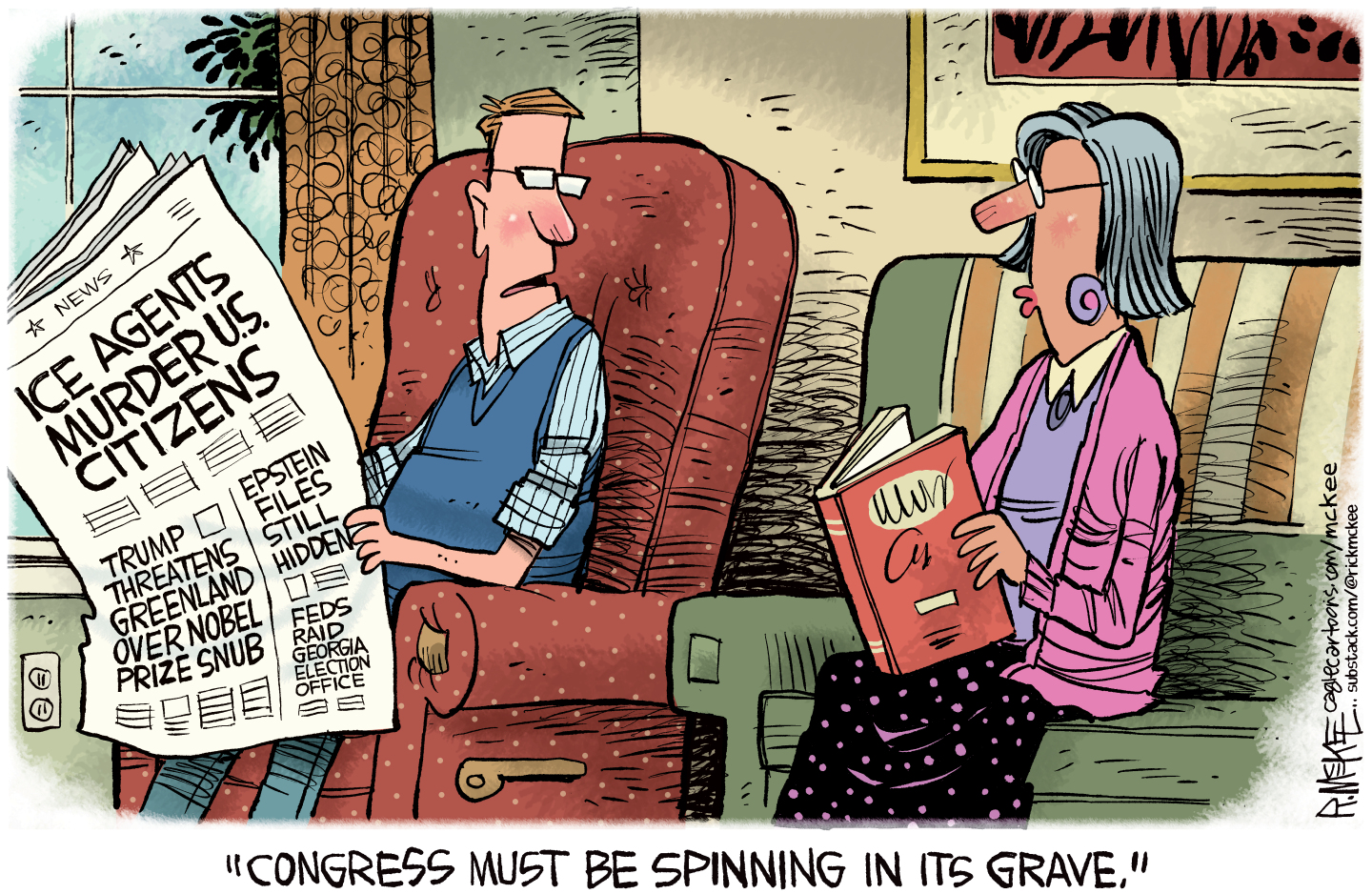

31 political cartoons for January 2026

31 political cartoons for January 2026Cartoons Editorial cartoonists take on Donald Trump, ICE, the World Economic Forum in Davos, Greenland and more

-

Political cartoons for January 31

Political cartoons for January 31Cartoons Saturday's political cartoons include congressional spin, Obamacare subsidies, and more

-

Syria’s Kurds: abandoned by their US ally

Syria’s Kurds: abandoned by their US allyTalking Point Ahmed al-Sharaa’s lightning offensive against Syrian Kurdistan belies his promise to respect the country’s ethnic minorities

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred