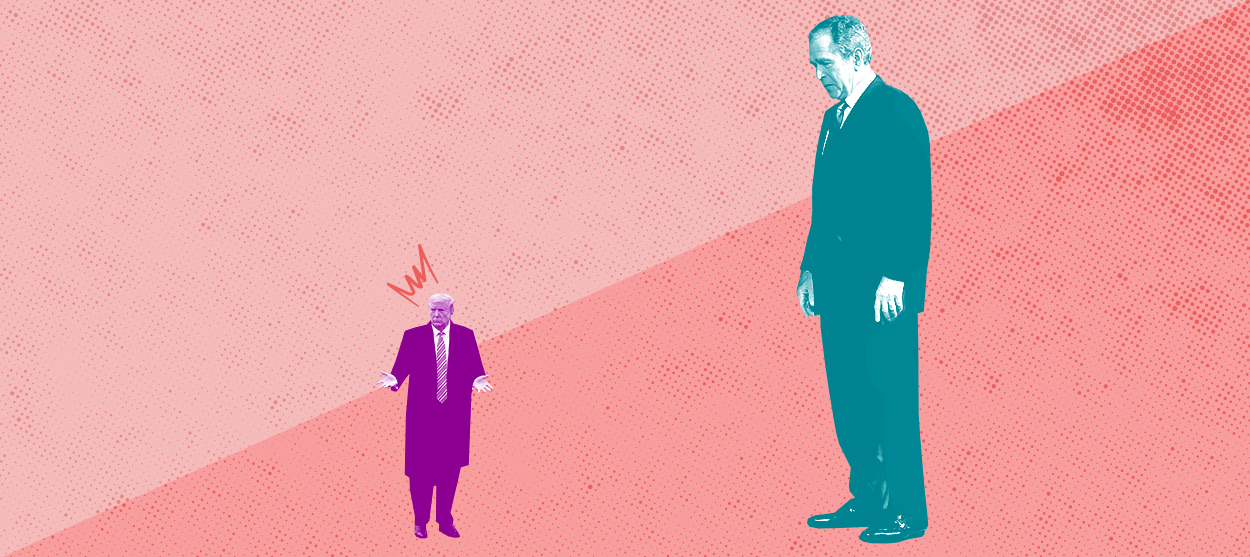

How George W. Bush exposed Trump's biggest failure

Trump cannot perform one of the vital functions of his office

How is it possible that I've come partially to respect and admire George W. Bush?

Maybe you've been wondering the same thing about yourself.

If you're like me, you were a severe critic of Bush during his presidency. You disliked the irresponsible tax cuts for the upper class that turned a budget surplus under his predecessor into a deficit. You rolled your eyes when he relied on his "gut" in dealing with foreign leaders. You were angered by his effort to privatize Social Security. You were distressed by his fondness for pursuing an agenda favored by the religious right, and especially his attempt to mobilize voters using prejudice against homosexuality. And most of all, you were furious that he made an unforced world-historical error in toppling the government of Iraq and destabilizing the Middle East for much of the next two decades.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Yet here we are, more than 11 years since he left office, and more than three years into the appalling presidency of Donald Trump, and Bush no longer seems quite so bad. Some of this is a function of the contrast with Trump. Instead of trying to eliminate the health insurance relied upon by millions, Bush oversaw the expansion of Medicare to cover prescription drugs. Instead of stoking xenophobia, attempting to shut down immigration, and imposing a travel ban on people from majority-Muslim countries, Bush consistently favored a more liberal immigration policy and took a stand against anti-Muslims bigotry after the 9/11 attacks. Instead of striving to put "America first" in all things and failing to take public-health issues seriously, Bush spearheaded an effort to fight AIDS in Africa — an initiative that was an enormous (and largely unheralded) humanitarian and geopolitical success.

The bright spots in Bush's policy record aren't enough to get me to overlook all the things that made me dislike him when he was in office. But the 3-minute video Bush released on Saturday points to something that I thoroughly took for granted during his presidency (and during every other presidency in my lifetime). It's a quality I've come to appreciate, admire, and miss terribly through the civic desert of the Trump administration: the capacity of a president to rise above partisanship to speak from and to the nation as a whole.

This isn't just some idle quality that sentimental Americans like their presidents to possess. It's one of the two fundamental responsibilities of the presidential office — to serve both as head of the executive branch of government and head of state. The second of these duties is as essential as the first — and for all of Trump's difficulty handling the managerial and policy challenges of running the executive branch, his inability to speak in high-minded terms about the good of the nation as a whole, about the need to rise above factionalism, and about our capacity to feel a part of a whole that's larger than ourselves is total, is one of his greatest failings as president. And it's been even more glaringly obvious since the pandemic took hold in mid-March. As much as anything over the past three years, Bush's video helps us to recognize this shortcoming for the fatal flaw that it is.

It's not just that the video is rhetorically and visually effective, with the former president speaking movingly (over images of medical workers and ordinary Americans wearing masks) about "how small our differences are" and how "in the final analysis, we are not partisan combatants. We are human beings, equally vulnerable and equally wonderful in the sight of God." Those and other lines in the video stir us because that's how presidents, in their capacity as heads of state, are supposed to talk. They don't speak as political actors out to vanquish ideological enemies. They speak as if they reside in a civic space shared by all political actors, on every side of every conflict that divides the polity. They seek to elevate themselves above the political fray and communicate to each and every one of us first and foremost as Americans.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Achieving this exalted position is often a challenge for presidents — precisely because they are expected to fulfill two roles at once, one political and one extra-political. Other governmental systems divide things up differently. A prime minister, for example, is the head of the party (or coalition of parties) that constitutes a majority in the legislature, but someone else — a monarch, a separately elected ceremonial official — serves as head of state. The United States expects the president to perform both duties, despite the sometimes considerable tension between the two roles.

Most presidents have managed to pull it off. On the campaign trail, at fundraisers, in meetings with advisers and senior executive branch officials, in private arm-twisting sessions with members of Congress — in all of these roles, a president acts and speaks as the head of his party, pushing its agenda, seeking partisan advantage, and doing battle with members of the other party. In these capacities, the president is a political actor.

But in other roles — addressing the nation in a time of domestic or international crisis, delivering the State of the Union speech to Congress and the country, meeting with foreign counterparts privately, in press briefings, and at state dinners — the president speaks differently. In these settings, he is the head of state, the country's leader, charged with using his considerable powers to do what is best for the political community as a whole, not just the parts represented by his own party.

This is part of the job that Trump is thoroughly incapable of performing. Instead of aspiring to unity, he exudes divisiveness and provokes antagonism with everything he says. That's how he does politics, and it's been incredibly effective for him. But it is incompatible with serving as the American head of state. Instead of binding the nation together with his words, his constant vituperation tears it apart.

Examples of Trump falling short of the dignity of his office are legion. It has never ceased to be appalling. (This includes Trump's typically petty and self-absorbed tweet in response to Bush's video.) But only since the pandemic took hold have we really begun to sense the full consequences of having a president who cannot perform one of the vital functions of his office — which is to ennoble and console the country in a wrenching crisis as only a head of state can. In all the hours Trump has spent speaking to the country since mid-March, how much time has he devoted to expressions of condolence or sympathy for the nearly 70,000 people who have thus far died from COVID-19? Five minutes? It's outrageous.

But it is also our reality — in a country without a head of state. This is the glaring absence that George W. Bush's video helps to highlight. Whatever Bush's flaws as a president — and there were many — he was nonetheless an effective head of state. Hearing familiar presidential cadences spoken by the voice of a man who once held the office cannot help but bring into sharp relief what we have lost — and what, in a time of national crisis, we sorely lack.

Want more essential commentary and analysis like this delivered straight to your inbox? Sign up for The Week's "Today's best articles" newsletter here.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.

-

Will SpaceX, OpenAI and Anthropic make 2026 the year of mega tech listings?

Will SpaceX, OpenAI and Anthropic make 2026 the year of mega tech listings?In Depth SpaceX float may come as soon as this year, and would be the largest IPO in history

-

Reforming the House of Lords

Reforming the House of LordsThe Explainer Keir Starmer’s government regards reform of the House of Lords as ‘long overdue and essential’

-

Sudoku: February 2026

Sudoku: February 2026Puzzles The daily medium sudoku puzzle from The Week

-

The ‘mad king’: has Trump finally lost it?

The ‘mad king’: has Trump finally lost it?Talking Point Rambling speeches, wind turbine obsession, and an ‘unhinged’ letter to Norway’s prime minister have caused concern whether the rest of his term is ‘sustainable’

-

A running list of everything Donald Trump’s administration, including the president, has said about his health

A running list of everything Donald Trump’s administration, including the president, has said about his healthIn Depth Some in the White House have claimed Trump has near-superhuman abilities

-

Trump sues IRS for $10B over tax record leaks

Trump sues IRS for $10B over tax record leaksSpeed Read The president is claiming ‘reputational and financial harm’ from leaks of his tax information between 2018 and 2020

-

‘Implementing strengthened provisions help advance aviation safety’

‘Implementing strengthened provisions help advance aviation safety’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Does standing up to Trump help world leaders at home?

Does standing up to Trump help world leaders at home?Today’s Big Question Mark Carney’s approval ratings have ‘soared to new highs’ following his Davos speech but other world leaders may not benefit in the same way

-

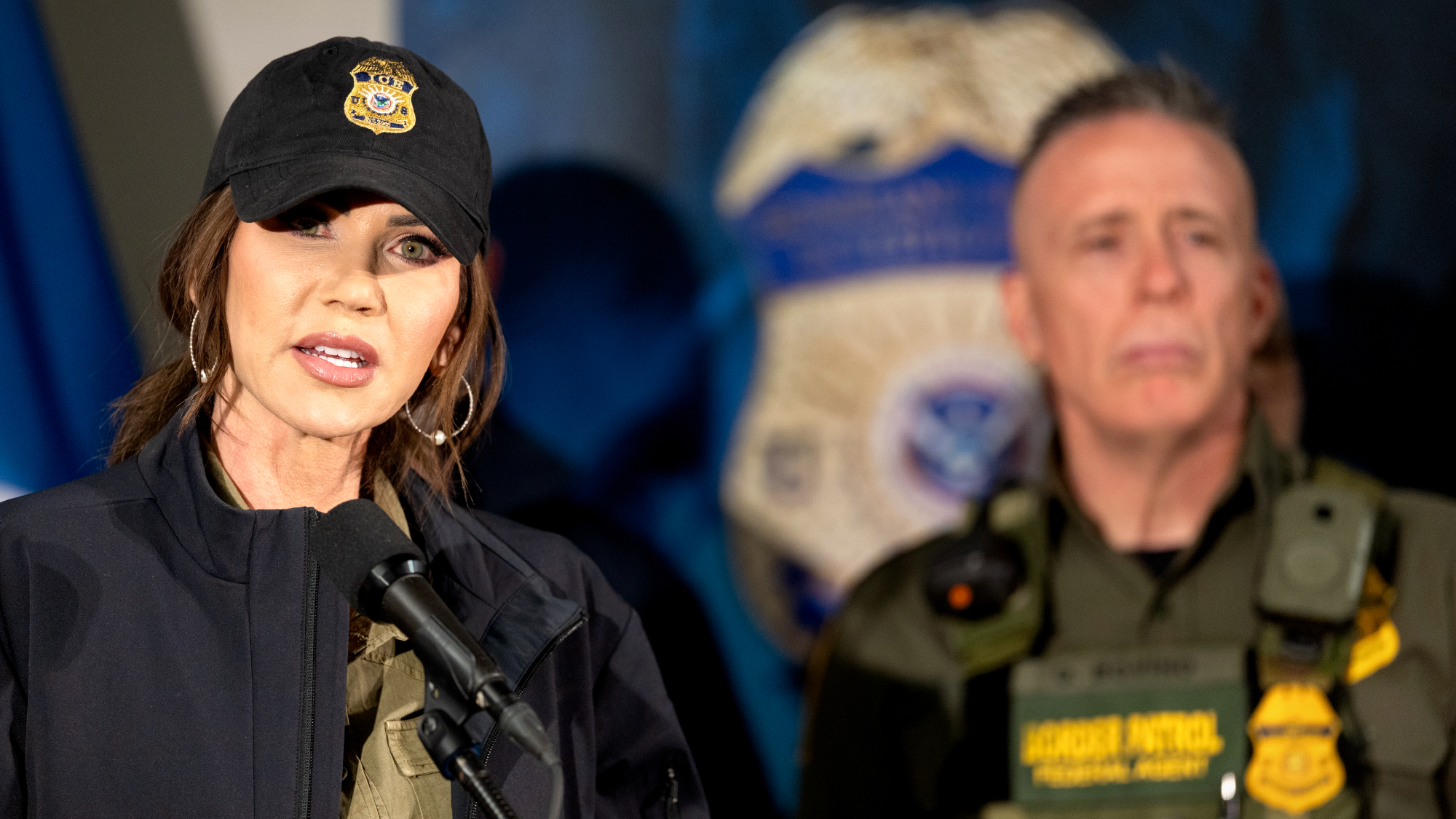

Democrats pledge Noem impeachment if not fired

Democrats pledge Noem impeachment if not firedSpeed Read Trump is publicly defending the Homeland Security secretary

-

Trump: A Nobel shakedown

Trump: A Nobel shakedownFeature The president accepts gold medal he did not earn

-

Trump inches back ICE deployment in Minnesota

Trump inches back ICE deployment in MinnesotaSpeed Read The decision comes following the shooting of Alex Pretti by ICE agents