The Republican plot to steal the 2024 election

Redistricting is the next step on a path to one-party rule

The redistricting process kicked off this week in Washington. The Census Bureau released initial data from the 2020 census Monday afternoon, (much later than usual thanks to a combination of the pandemic, Donald Trump's efforts to stop unauthorized immigrants from being counted, and his administration's general flailing incompetence), which means that congressional district boundaries will soon be redrawn to account for changes in population.

These changes will probably tend to benefit the Republican Party, as conservative states will get more seats — for instance, Texas will gain two seats, while New York, California, and Illinois will all lose one. Republicans are also certain to use the process to try to gerrymander themselves as many additional congressional seats as possible by leveraging their control of a majority of state legislatures. And that is just the opening tactic in a long-term strategy to abolish American democracy and set up one-party rule.

The basic strategy goes like this. First, win control of state legislatures, then gerrymander the state district boundaries such that it's virtually impossible to lose, and add further protection with vote suppression laws making it harder for liberals to cast their ballots. Then, leverage control of the state legislatures in a post-census year to gerrymander the congressional district boundaries and gain a large advantage in the national House vote. This was exactly what happened after the previous census in 2010, when a fortunately-timed Republican wave victory allowed them to cement a roughly 4-5 point handicap in House elections and control of the chamber for eight years, along with control of dozens of state legislatures.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Today in Michigan, gerrymandering means Republicans enjoy a 3.4-point handicap in the state House and a 10.7-point handicap in the state Senate; in Pennsylvania, it's a 3.1-point handicap in the House and a 5.9-point handicap in the Senate; and in Wisconsin, a 7.1-point handicap in the House and a 10.1-point handicap in the Senate.

Though some of those 2010-vintage gerrymanders have been eroded or taken down through the courts, new ones will be attempted in every state Republicans control this year that do not have nonpartisan redistricting commissions (which is most of them). As Ryan Grim estimates at The Intercept, a fresh hardcore House gerrymander would likely net the GOP 15-20 House seats — easily enough to let them take the majority, if the 2022 electorate looks anything like 2020. And thanks to the conservative hammerlock on the Supreme Court, the new gerrymanders and vote suppression measures are virtually guaranteed to be blessed as "legal" (in conservative jurisprudence, something is constitutional if it benefits Republicans).

It's impossible to gerrymander the Senate, of course, but luckily for Republicans that chamber is inherently gerrymandered due to the large number of disproportionately white, low-population rural states that lean conservative. The swing seat in the Senate is biased something like 7 points to the right.

If the GOP can win the House and Senate in the 2022 midterms, and if they retain control of a handful of swing-state legislatures, then they will be in a perfect position to steal the presidency in 2024. As Jonathan V. Last explains at The Bulwark, it would be quite simple to steal a presidential election within the formal rules of America's electoral system, though of course it would be a blatant violation of the entire spirit of the Constitution. The anachronistic, nonsensical legal structure that governs presidential elections says that if Congress does not certify a majority winner in the Electoral College, then the next president will be chosen by a vote of the House — but each state delegation bizarrely gets only one vote. Wyoming's one representative will get the same sway as the 50-odd representatives in California. (The vice president would be chosen by the Senate, a relic of the old rules in which that office had a separate election.)

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Incidentally, one gets a sense of how utterly goofy the presidential election process is by considering the fact that not only is it possible to tie the above House vote, since there are 50 states, it is also possible to tie the individual state delegation votes, because numerous states have an even number of representatives. There is no process to break such ties, and this process has not been used since 1824.

At any rate, it follows that if Republicans have a majority of the House delegations in 26 states (as they currently do despite being in the minority overall), they only have to foul up enough state certifications to prevent an Electoral College majority, and then have their state delegations hand the presidency to their own candidate no matter how badly he or she lost the popular vote.

Republicans have been clearly signaling for months they are going to try this. Indeed, they already tried something like it in 2020 — Trump filed dozens of lawsuits attempting to stop the state vote certifications based on fabricated accusations of voter fraud, and tried to bully Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger into meddling with the vote totals in his state. When that didn't work, Trump sicced a violent mob on the Capitol to halt the certification in Congress. The Capitol putsch was an act of desperation, but a majority of House Republicans did indeed vote to overturn the 2020 election even so. Trump also came quite close to disrupting the certification in Michigan, which only happened because one Republican member of the electoral oversight board, Aaron Van Langevelde, refused Trump's threats and entreaties.

As Last notes, Republicans are now taking ever-more extreme steps to make sure that doesn't happen again. Van Langevelde has been sacked and replaced with a GOP apparatchik. Most Republican elected officials who did not try to overturn the 2020 election or otherwise criticized Trump have come under ferocious pressure from conservative media, state parties, and their own voters; several have already announced their retirements or are facing primary challengers. Raffensperger has also drawn a primary challenge, and the Georgia state legislature now has asserted direct control over the state's electoral oversight board as part of the state's new vote suppression law. In Arizona, Republican legislators have proposed a law allowing the state legislature to overturn the state's presidential election results at any time before the inauguration. Just like Trump's plot to steal the 2020 election, it's all happening in plain sight.

If they succeed and take full control of the federal government, it would be a trivial matter to rig the electoral system such that Democrats cannot ever again win national power. Similar to the strategy their ideological ancestors used to create Jim Crow, they could simply pass a bunch of facially neutral laws that make it exceptionally difficult to vote in cities or other liberal bastions, and then get their partisan judges on the Supreme Court to rubber-stamp it all as super constitutional, no really.

One will search in vain for any sense of urgency among elected Democrats to deal with this authoritarian threat. So-called moderates like Sens. Joe Manchin (D-W.V.) and Krysten Sinema (D-Ariz.) are not only so far unwilling to get rid of the filibuster to pass voting rights protections, they are also still pretending like Republicans are good faith negotiators, like some man insisting a shark is just misunderstood while his leg is halfway down its throat. If they don't black in and reckon with the parlous state of American institutions, and get behind strong protections for voting rights and a ban on partisan gerrymandering at a minimum, 2020 might be the last competitive election in United States history.

Ryan Cooper is a national correspondent at TheWeek.com. His work has appeared in the Washington Monthly, The New Republic, and the Washington Post.

-

10 concert tours to see this winter

10 concert tours to see this winterThe Week Recommends Keep cozy this winter with a series of concerts from big-name artists

-

What are portable mortgages and how do they work?

What are portable mortgages and how do they work?the explainer Homeowners can transfer their old rates to a new property in the UK and Canada. The Trump administration is considering making it possible in the US.

-

What’s the best way to use your year-end bonus?

What’s the best way to use your year-end bonus?the explainer Pay down debt, add it to an emergency fund or put it toward retirement

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Dutch center-left rises in election as far-right falls

Dutch center-left rises in election as far-right fallsSpeed Read The country’s other parties have ruled against forming a coalition

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

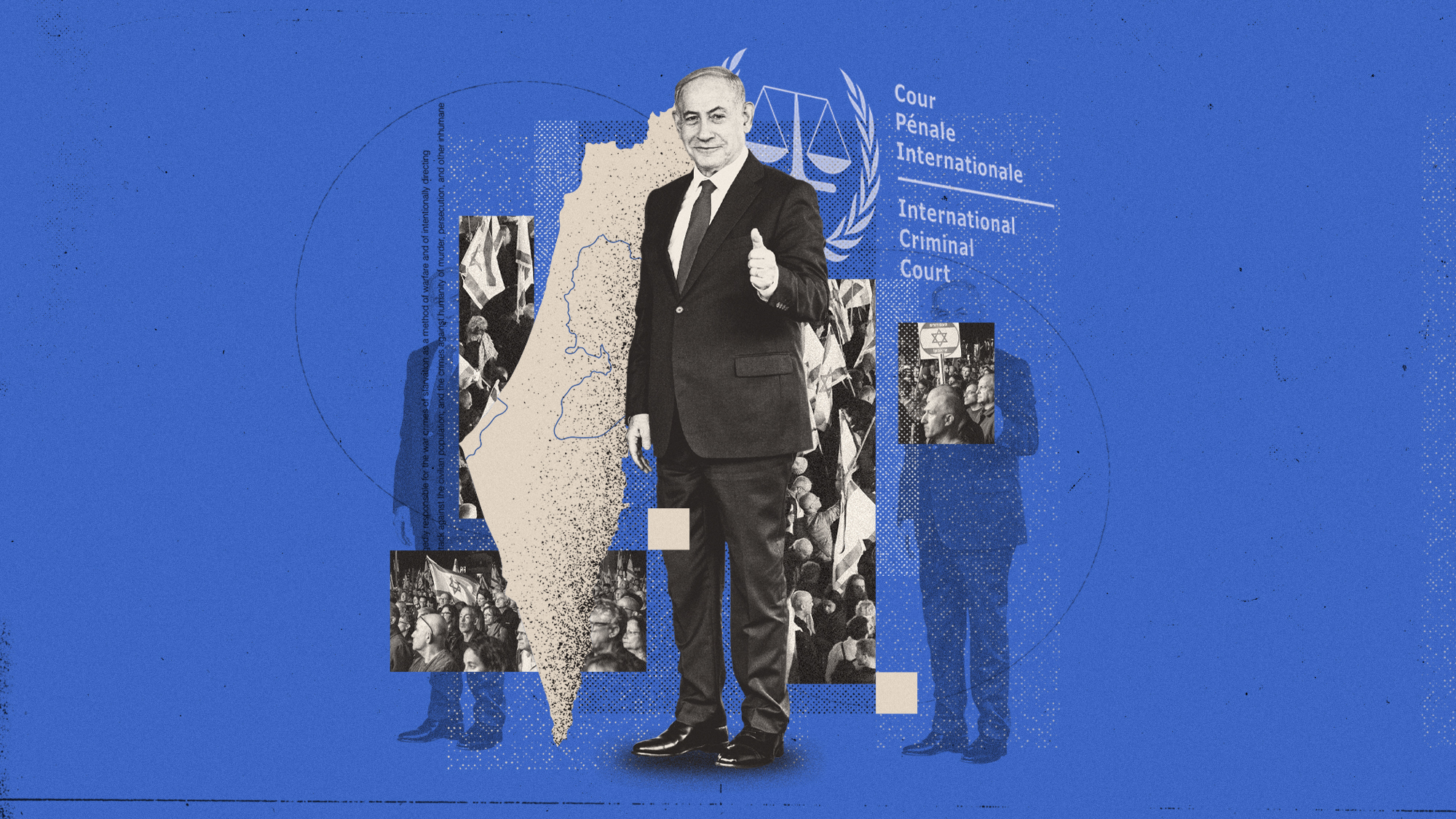

Has the Gaza deal saved Netanyahu?

Has the Gaza deal saved Netanyahu?Today's Big Question With elections looming, Israel’s longest serving PM will ‘try to carry out political alchemy, converting the deal into political gold’

-

Brazil’s Bolsonaro sentenced to 27 years for coup attempt

Brazil’s Bolsonaro sentenced to 27 years for coup attemptSpeed Read Bolsonaro was convicted of attempting to stay in power following his 2022 election loss

-

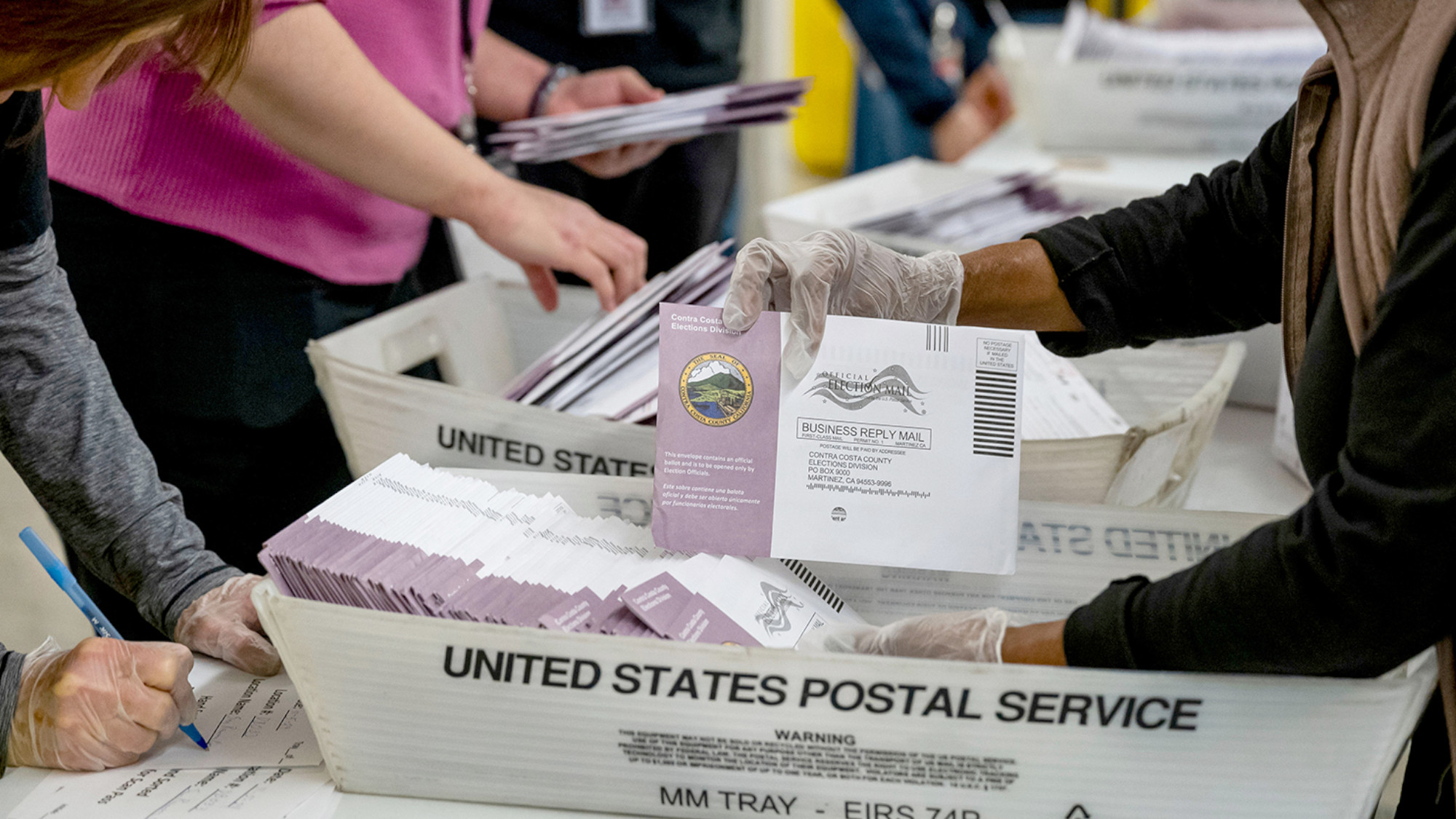

Voting: Trump's ominous war on mail ballots

Voting: Trump's ominous war on mail ballotsFeature Donald Trump wants to sign an executive order banning mail-in ballots for the 2026 midterms

-

The push for a progressive mayor has arrived in Seattle

The push for a progressive mayor has arrived in SeattleThe Explainer Two liberals will face off in this November's election

-

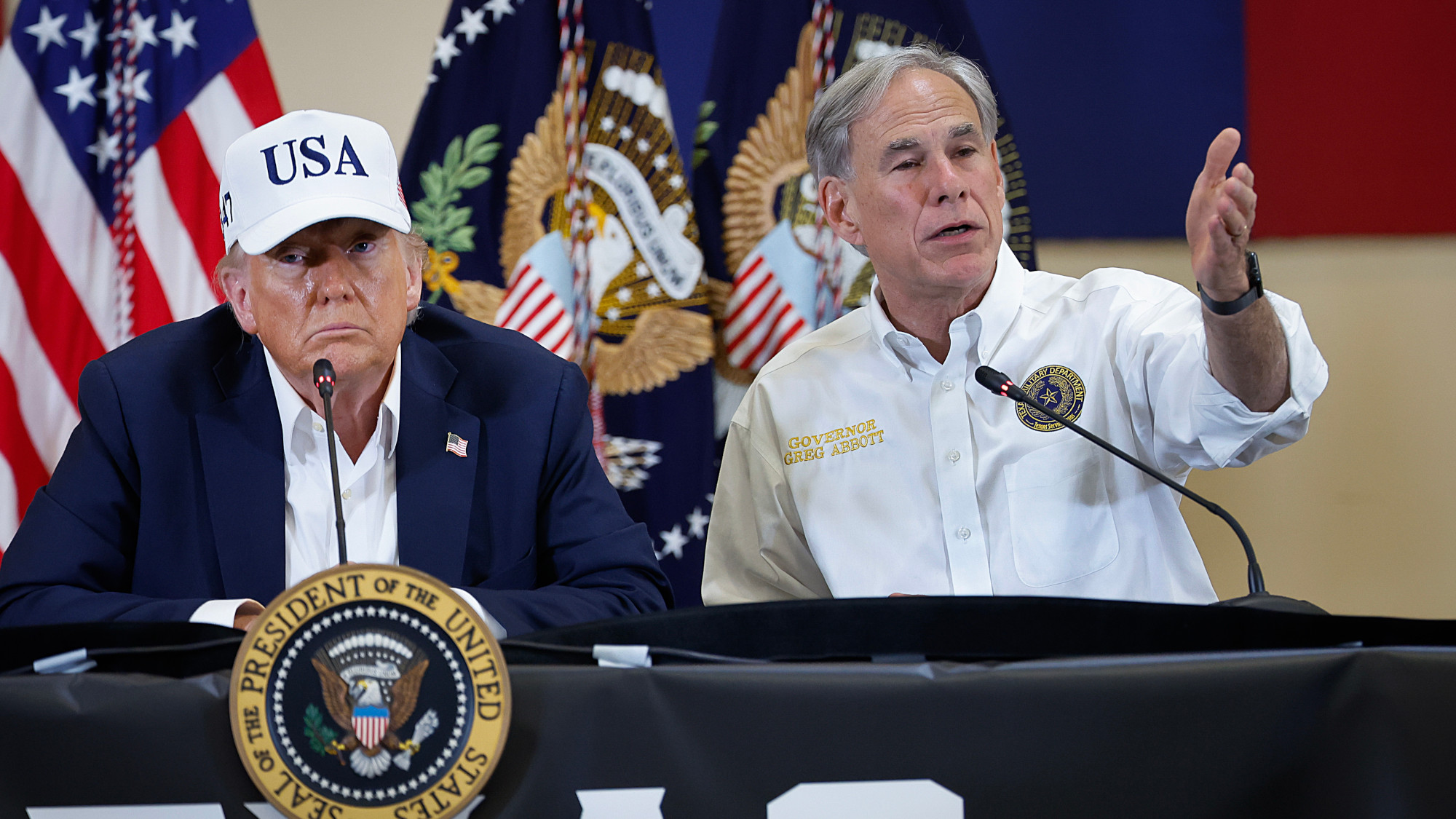

Redistricting: How the GOP could win in 2026

Redistricting: How the GOP could win in 2026Feature Trump pushes early redistricting in Texas to help Republicans keep control of the House in next year's elections