Death to Pandora? A guide to the looming music copyright war

Congress is revamping U.S. copyright law, and Pandora, Spotify, AM/FM radio — and music lovers — could pay a steep price

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

There's a big, contentious battle brewing in Washington and you might not even know about it. But you should, especially if you like music.

Congress is looking at a complete overhaul of U.S. copyright law, and the most divisive issue involves money and music. The Justice Department also announced in June that it is revisiting a 70-year-old consent decree with the two organizations that collect and distribute songwriting royalties: ASCAP and BMI.

The smart money is on something in the music business changing in the near future. And all the major players agree on just one thing: The cobbled-together patchwork of laws and legal precedents holding together the U.S. music industry right now is outdated and overly complicated. But as Rep. Jim Sensenbrenner (R-Wis.) said to the various interests testifying at a June 25 House Judiciary Committee hearing, "Getting you all together, and getting on one page, will probably happen two days after the sun rises in the west."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Here's an introduction to the big battles coming up for the future of the music business, the key groups, and what they are asking for:

THE PLAYERS

Songwriters/publishers

The people who write songs and the companies that publish them (which mostly means shopping them around) are legally entitled to payment basically whenever one of their songs is played in public — whether on the radio, in a bar, or streamed online, for example. The songwriters and publishers join one of three performing rights organizations (PROs) — generally ASCAP or BMI, but sometimes the much smaller SESAC — which collect these royalties and distribute them to their members. Their overarching goal in this battle is to find ways to increase their royalty rates.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Musicians

Many musicians are also songwriters — but, of course, not all of them are. Many pop artists don't write their songs, nor do many jazz musicians or classical music performers, and even songwriters perform other people's songs.

These musicians are leading the charge to get AM/FM radio stations to pay royalties to the recording artists, not just the songwriters and publishers. They're also hoping to get Congress to extend federal copyright protections to music recorded before early 1972.

As singer-songwriter Taylor Swift noted in a recent Wall Street Journal op-ed, "piracy, file sharing, and streaming have shrunk the numbers of paid album sales drastically" in the past decade, and "it isn't as easy today as it was 20 years ago to have a multiplatinum-selling album." Swift earned nearly $40 million in 2013, according to Billboard, so she's doing fine, but most musicians of a certain stature are trying hard to figure out how to make up for lost CD revenue.

Major record labels/RIAA

The Big Three record labels — Sony Music Entertainment, Universal Music Group, and Warner Music Group — and their trade association, the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA), are some of the biggest guns in this fight.

The record companies typically own the rights to music recorded on their labels, so they are lobbying for terrestrial radio stations to start paying royalties for playing their recordings and for internet music services to pay higher royalties. And since many record companies also have large publishing arms, they also want — and sometimes apparently collude with — the performing rights organizations to get higher songwriting royalty rates from everybody, but especially services like Pandora.

Satellite radio, Pandora, and other digital music-streaming services

As the new kids on the block, digital radio and music-stream services like Sirius XM and Pandora, have the most to lose in this fight. Pandora, the most popular online radio service, is the center of much of the litigation and legislation in the music industry. Other large internet streaming interests like Apple, Google's YouTube, Rhapsody, and Amazon are represented by the Digital Media Association.

AM/FM radio broadcasters/NAB

So-called terrestrial radio — AM and FM stations — are represented in this fight by the National Association of Broadcasters (NAB). They mostly would prefer that the status quo hold.

THE BIG BATTLES

BMI and ASCAP consent decrees

In 1941, the big associations of publishers and musicians, BMI and ASCAP, settled antitrust lawsuits brought by the federal government by agreeing to binding consent decrees. Basically, anyone who wants to play any popular song in public has to get permission from BMI or ASCAP — and at the time, ASCAP was using its market dominance to demand ever-higher royalties in the 1930s. It raised rates for broadcasters by more than 400 percent that decade, then tried to double them again in 1940, leading to a boycott and the formation of BMI.

Under the consent decrees that settled the 1941 Justice Department lawsuits, BMI and ASCAP have to allow anyone to license music from their portfolios. Importantly, these royalty agreements are overseen by two federal courts, one for each PRO, instead of unsupervised negotiations.

The decrees have been modified over the years, most recently in 1994 (BMI) and 2001 (ASCAP) — which, as ASCAP notes, was "before the introduction of the iPod."

For years, ASCAP and BMI have been seeking to loosen the constraints or even end their consent decrees, and on June 4, the Justice Department said it is "undertaking a review to examine the operation and effectiveness of the consent decrees." It appears that everything is on the table.

ASCAP, BMI, and music publishers want the consent decrees voided or, barring that, modified so that publishers can partially withdraw their music from the PROs' catalogues for certain licensees — notably, Pandora — forcing the music streaming services to negotiate directly with large publishers outside of the purview of the federal rate courts. They also want to replace the federal rate courts with arbitration — presumably because Pandora keeps beating them in the rate court, most recently in March, in a comprehensive and damning opinion by U.S. District Judge Denise L. Cote.

The goal for music publishers is to charge higher royalty rates, especially for digital streaming services, so obviously Pandora, Sirius XM, and groups like the Digital Music Association oppose weakening the consent decree.

Songwriters Equity Act

This bill, introduced in February and being promoted by some powerful Republican senators, is intended to increase the performance and mechanical royalties for songwriters by adjusting how the rate courts determine fair royalty amounts. This would be good for some songwriters, PROs, and music publishers, and less good for digital streaming services and, most likely, consumers. You can read more about this bill here.

RESPECT Act

Congress significantly reformed America's copyright laws in 1976, but four years before that — on Feb. 15, 1972 — it created a federal copyright protection for recordings made only on that date and after. To illustrate the arbitrary and cruelly whimsical nature of this decision, Rep. Darrell Issa (R-Calif.) held up a copy of Neil Young's classic LP Harvest at the June 25 hearing, noting that because it was released on Feb. 14, 1972, Young wasn't eligible for most non-songwriting royalties from the record. These older records are covered under some state laws.

On May 29, a bipartisan coterie from the House introduced the Respecting Senior Performers as Essential Cultural Treasures Act, or RESPECT Act, which would extend federal copyright protection to pre-1972 recordings, but only for internet, satellite, and cable music services. This bill is probably the most likely of any of the music legislation to pass, because no group publicly opposes paying older musicians or thinks the pre-/post-1972 dividing line makes much sense.

The fight, though, will be over how much copyright protection to extend to the pre-1972 recordings. The RESPECT Act only covers services like Sirius XM and Pandora, and the RIAA and major record labels support this approach (after opposing all federal copyright protection of pre-1972 music for decades), but the U.S. Copyright Office and musician advocacy groups like the Future of Music Coalition (FMC) prefer full protections for the older recordings.

"Observers of politics are no doubt familiar with the concept of 'strange bedfellows,'" says FMC policy and education chief Casey Rae. "In this instance, you've got services like Pandora, artist advocates, copyright maximalists, academics, libraries, archivists, reissuers, and more calling for full protections. Only the major labels seem resistant." Rae speculates that the labels may be hoping to pursue lucrative lawsuits in state courts, or don't want the hassle of determining who owns the copyright to what recordings, or fear that "a proper accounting of their copyrights likely means a proper accounting of what they owe artists."

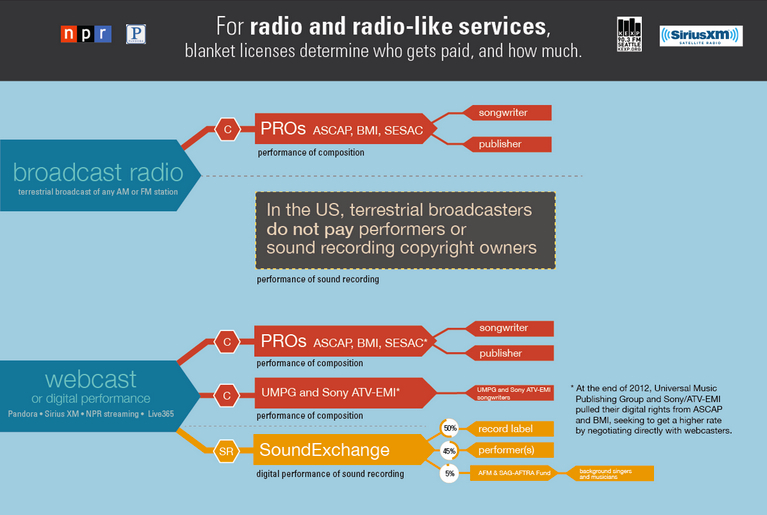

Protecting the Rights of Musicians Act

In the U.S., AM/FM radio stations pay songwriters for the music they broadcast but don't pay musicians or record labels; internet and satellite radio stations pay royalties to both songwriters and recording artists every time one of their songs is streamed. On May 7, Rep. Marsha Blackburn (R-Tenn.) introduced the Protecting the Rights of Musicians Act to iron out this discrepancy by making AM/FM stations pay the labels and performing artists too. This chart, from the Future of Music Coalition, explains the current flow of money:

Terrestrial radio stations and the National Association of Broadcasters oppose this bill, obviously, but musicians, record labels, and the internet and satellite radio interests support making AM/FM stations pay up. The NAB's Charles Warfield was left defending the status quo in the June 25 House hearing, arguing that "our unique system of free airplay for free promotion has served both the broadcasting and recording industry well for decades."

He was backed up by Radio Music License Committee Chairman Ed Cristian, who cuttingly argued that the terrestrial radio business isn't "some vast pot of riches" that "can be tapped as a bailout for a recording industry that has failed to execute a digital strategy." Most lawmakers seemed more inclined toward the argument from everyone else for a level playing field for digital and analog broadcasts.

How this all fits together, and what it might mean

If Congress acts at all this year, it will probably wrap the various proposals into one omnibus bill covering all aspects of music licensing, or even broader copyright law in the U.S. But most of the changes in the music parts of copyright law are aimed at the biggest area of growth — and newest wrinkle in the music industry — digital streaming. Add in the potential changes to the BMI and ASCAP consent decrees, and the biggest risk in this legislative endeavor is for online music services, the largest of which is Pandora.

"There is little debate that the current copyright laws need to be comprehensively reviewed and updated to reflect current market realities," says Chris Versace at Fox Business. But most of the proposals being considered "would be devastating to streaming music providers."

Services like Pandora already pay over 60 percent of their revenue in licensing fees while others pay far less for delivering the same service. As a result, services like Pandora have been unable to see profitability and sustainability is already in serious question. Further raising rates would likely be fatal. [Fox Business]

There is no group representing the interests of consumers. That's Congress' job. Here's hoping they keep that in mind.

Peter has worked as a news and culture writer and editor at The Week since the site's launch in 2008. He covers politics, world affairs, religion and cultural currents. His journalism career began as a copy editor at a financial newswire and has included editorial positions at The New York Times Magazine, Facts on File, and Oregon State University.