Why even non-Jews should celebrate Yom Kippur

The case for ritualized apologizing

It makes sense that Passover is the Jewish holiday with the biggest crossover appeal. What's not to like about a night of eating, drinking, and celebrating the passage from slavery to freedom?

And it makes sense that Yom Kippur, or the Day of Atonement, is the one with the smallest. A holiday dedicated to repentance, it involves a 25-hour fast and a long day of intensive prayer focused on individuals' sins. But one aspect of the holiday, should it be adopted by the culture-at-large, would do us all a lot of good: the custom of ritualized apologizing.

For Jews, repentance isn't something that happens between God and themselves, but also between individuals and the people around them. Teshuvah, which translate to "return," requires Jews to apologize to the people in their lives. This can happen all year, but the mandate to do so is especially strong during the 10 days between Rosh Hashanah (the Jewish New Year) and Yom Kippur.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

So why am I endorsing ritualized apologies as the best Jewish export, better than bagels or matzo ball soup? Because saying sorry is both one of the hardest things humans can do and also one of the most necessary. And being forced to say sorry by way of ritual makes doing it a little easier.

There are a number of reasons apologies have gotten more difficult in recent years. Writing in Psychology Today, Aaron Lazare, author of the book On Apology, looks at how the winner-takes-all atmosphere that so many of us live in today works against the practice of saying sorry.

Despite its importance, apologizing is antithetical to the ever-pervasive values of winning, success, and perfection. The successful apology requires empathy and the security and strength to admit fault, failure, and weakness. But we are so busy winning that we can't concede our own mistakes. [Psychology Today]

Then there is the fact that our communications have been so sped up that we rarely have the time to slow down and process what is actually going on. Our overflowing in-boxes and constantly updating social feeds have made us all too comfortable with scrolling past or deleting an issue rather than reflecting on it. And there is always something else to read, providing us with an all-too-easy escape route for an uncomfortable situation. But of course there is a real risk to approaching our behavior and personal interactions like we do a tweet.

The act of teshuvah discourages such thinking, pulling us away from the idea that misunderstandings and indiscretions can be so easily resolved. Here is how you do it:

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

1. Be regretful: This involves thinking hard about what you did wrong and what kind of harm was experienced as a result.

2. Stop the offending behavior: You can't sincerely apologize for something you are still doing.

3. Confess to the sin and ask for forgiveness. Jewish law prescribes that this be done verbally and that we remain humble and contrite in our request.

4. Commit to never repeating it. This one is tough.

I'll be honest. I've been observing the practice of teshuvah for a few years now, and I never feel better afterward. I feel weak, a little lousy. More honesty: I've found myself apologizing for the same thing over and over again, year after year. My sin is pride and judgment, something that benefits me in my professional life as a cultural critic but is an imperfect instinct in the context of my personal life.

Still, I'd like to think I grow more self-aware year after year, and that I am getting a little better year by year, even if I will never fully overcome my weakness. At the very least, I hope that my apologies give those who I have offended a chance to heal.

The Talmud, an ancient collection of Jewish law and stories, claims that God created repentance before creating the universe. Whether one believes in God or not, it's a compelling concept, one that emphasizes how we are fated to misstep but that we also have the capacity to undo some or all of the harm we cause. But as the thinking goes, God only provided us with this tool. It is up to us to use it.

Elissa Strauss writes about the intersection of gender and culture for TheWeek.com. She also writes regularly for Elle.com and the Jewish Daily Forward, where she is a weekly columnist.

-

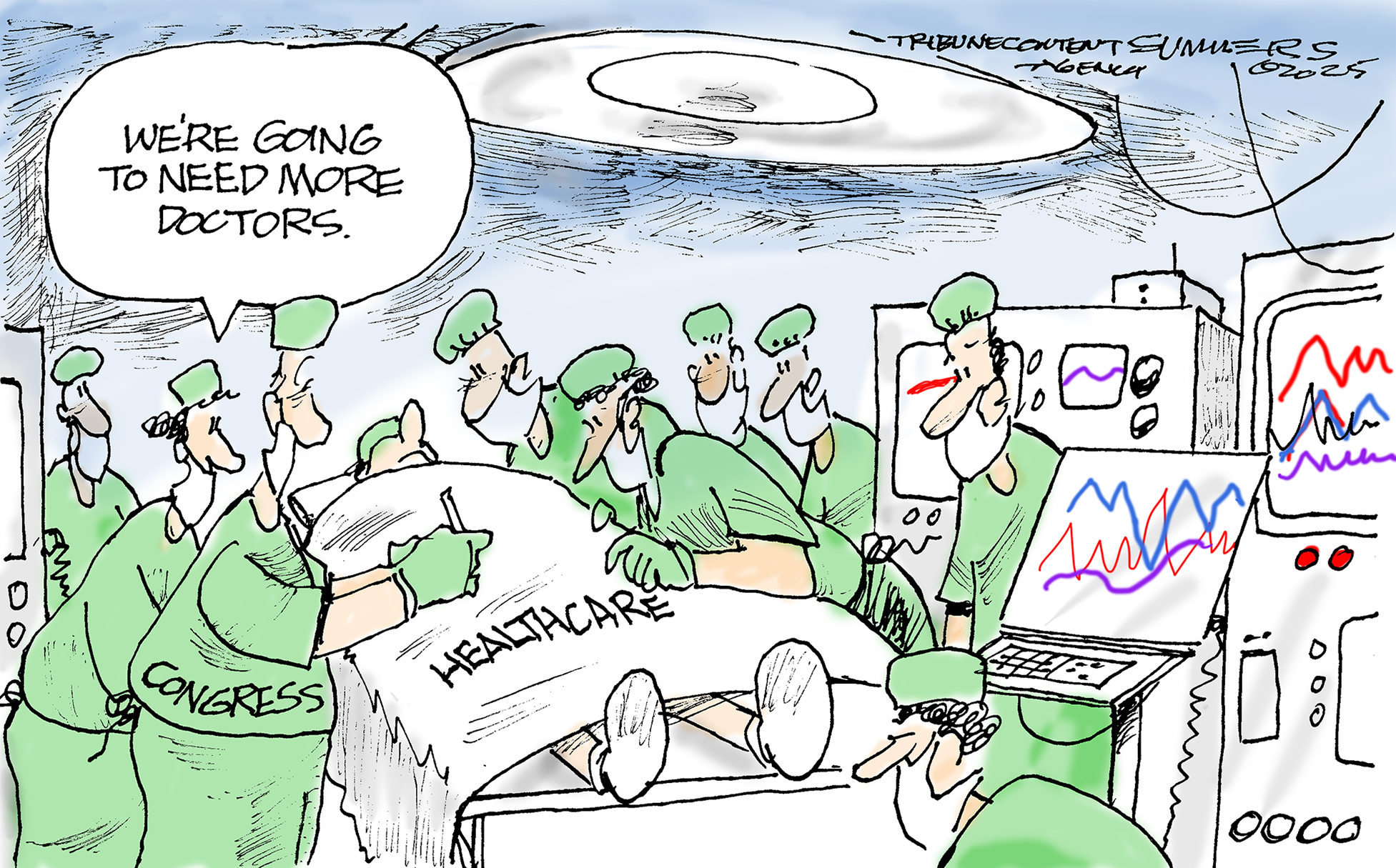

Political cartoons for December 13

Political cartoons for December 13Cartoons Saturday's political cartoons include saving healthcare, the affordability crisis, and more

-

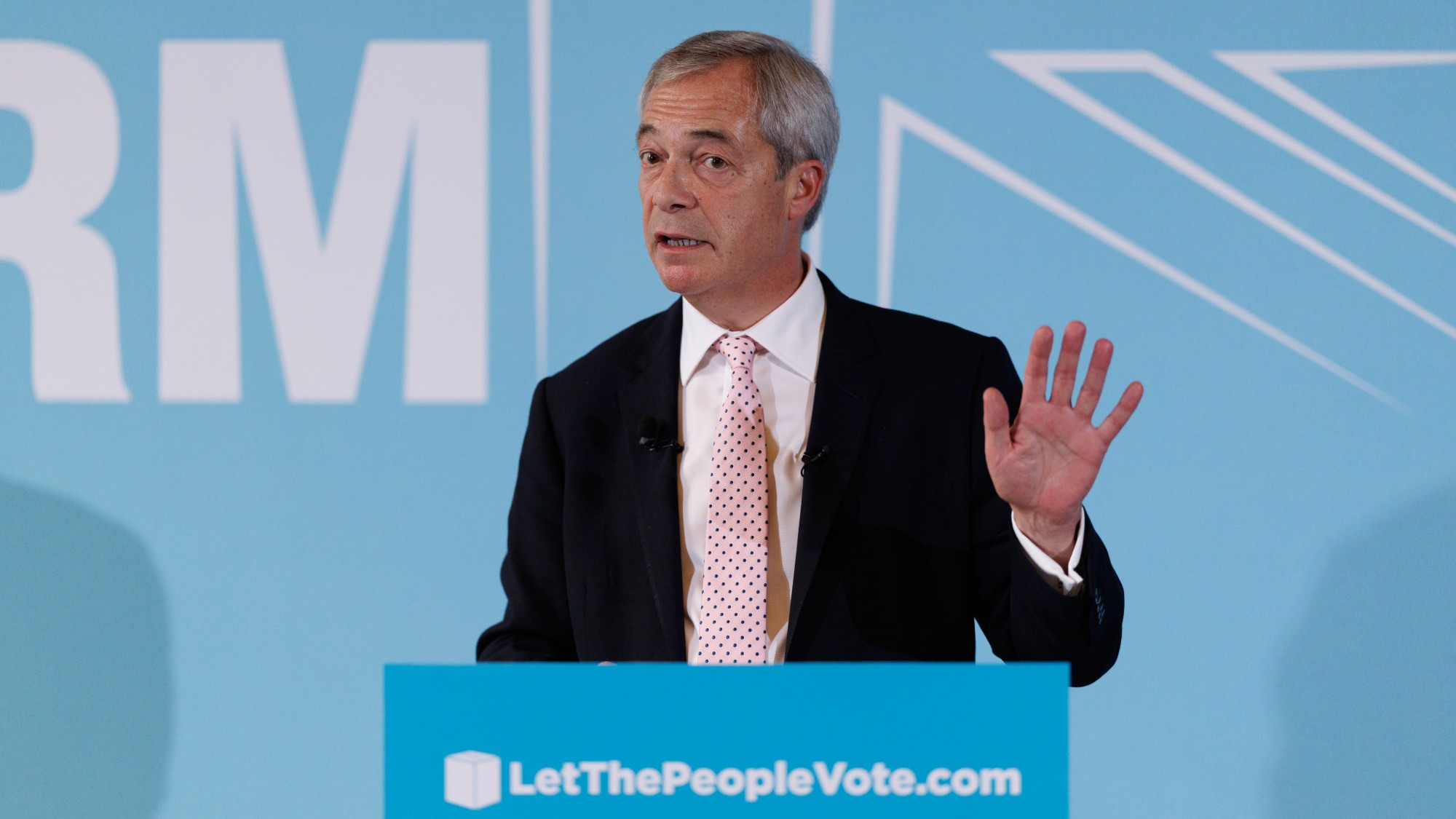

Farage’s £9m windfall: will it smooth his path to power?

Farage’s £9m windfall: will it smooth his path to power?In Depth The record donation has come amidst rumours of collaboration with the Conservatives and allegations of racism in Farage's school days

-

The issue dividing Israel: ultra-Orthodox draft dodgers

The issue dividing Israel: ultra-Orthodox draft dodgersIn the Spotlight A new bill has solidified the community’s ‘draft evasion’ stance, with this issue becoming the country’s ‘greatest internal security threat’