The ugly economics of chicken

Under Tyson's rules farmers take the risks, while Tyson gets most of the profits

KANITA YANDELL HAD called the Tyson plant again and again, for months, begging them to come, demanding help. She and her husband, Jerry, had been raising chickens for two decades, and they'd never been through anything like the last six months. It was a strange disease, or an industrial accident, or both. It was something gone wrong on a grand scale. The birds were simply dying. It seemed like they had started rotting even while they were still alive. She and Jerry worked 10-hour days, seven days a week. Their labor seemed to do nothing but dig them deeper and deeper into debt. But the Yandells had no choice but to continue working. Their home, their farm, and their livelihood depended on whether the birds lived or not.

About every eight weeks, a Tyson truck delivered chicks to the Yandell farm outside Waldron, Ark. Jerry and Kanita's job was to raise the tens of thousands of birds, fattening them up until Tyson returned six weeks later to collect them for slaughter. It was a routine the couple knew well, one that defined the rhythm of their 26-year marriage and the lives of their three boys.

It was a routine that collapsed in the fall of 2003, when the birds started dying overnight in great piles. Jerry and Kanita hadn't seen anything like it. Tyson field technicians visited the farm and looked inside the plastic freezers full of limp white carcasses. They told the Yandells to turn up the heat, turn on the fans, and give the birds more water.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Kanita walked through the houses and picked the rotten birds off each other. Their bodies were like soft, purple balloons by the time she gathered them. They fell apart to the touch, legs sloughing off the body when she tried to pick them up. It was like they were unraveling from the inside at a heated speed. She kept calling the Tyson field men, asking them to come and inspect the buckets full of liquefying birds.

Around Christmas, Kanita and Jerry realized it didn't matter. Whatever burned through the chickens had eaten their livelihood as well. They had taken on more than $260,000 in debt to build the chicken houses. The sickness wiped out the birds. And the dead birds wiped out their paycheck. This would be the last flock and the end of their farm. The end of their home.

A crew of Tyson men came to gather the last flock, wearing plastic suits as if fending off a plague. Kanita asked why they were dressed in biohazard suits. They told her the suits were a precaution, nothing to worry about.

"I'll be ruined by this," she said. "I'll lose my farm."

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

"I'm sorry," one of the men said.

"You look at my boys and you tell them how sorry you are about it," she said.

THE STRUGGLES ON the Yandells' farm could be observed on computers inside the offices of Tyson Foods. Tyson can measure the profitability of every square foot of space under a farmer's control, gauging how much weight the birds gained given the precisely measured amount of feed, water, and medicine Tyson provided. Tyson employees create graphs of each farm's profitability to see in real time how efficiently the farmer transforms feed into fatter chickens. The information is aggregated on computer servers at Tyson Foods' headquarters in Springdale, Ark., where engineers search through the vital statistics from farms stretching through Georgia to Delaware to Arkansas. Tyson's headquarters is the real seat of power in the new, vertically integrated meat industry.

To understand how vertical integration works, and how it controls the livelihoods of people like Jerry and Kanita Yandell, it is helpful to tour the wide expanse of concrete on the north side of town in Waldron. This concrete plain is the Tyson Foods plant. It is the heart of the city, its economic lifeblood and the reason for Waldron's existence.

The Tyson plant is a self-contained rural economy. Within its fenced confines are a slaughterhouse, a feed mill, a food-processing factory, a trucking lot and maintenance shop, administrative offices, a railroad spur, and a sewage plant. Decades ago, a big meat-producing town like Waldron — which pumps out millions of pounds of chicken products each week — might have contained a small network of businesses that supported and thrived from the local meat industry. There might have been several hatcheries that provided baby chicks to farmers, one or two slaughterhouses to kill the birds when they were grown. Feed mills would have mixed raw grains into chicken food to sell to local farmers, and local trucking companies would have hauled the feed and the birds between factories and the scattered farms where chickens were raised.

Under Tyson, all these businesses have been drawn onto one property. The company controls every step of meat production. The company's control spans the lifetime of the animals it raises. Before there is a chicken or an egg, there is Tyson. The company's geneticists select which kinds of birds will be grown. The birds begin their brief life at the Tyson plant, within the heated hive of its industrial hatchery. The company produces more than 2 billion eggs a year, but none of them are sold to consumers. They are all hatched inside the company's buildings, and the chicks are transported in Tyson trucks to Tyson farms.

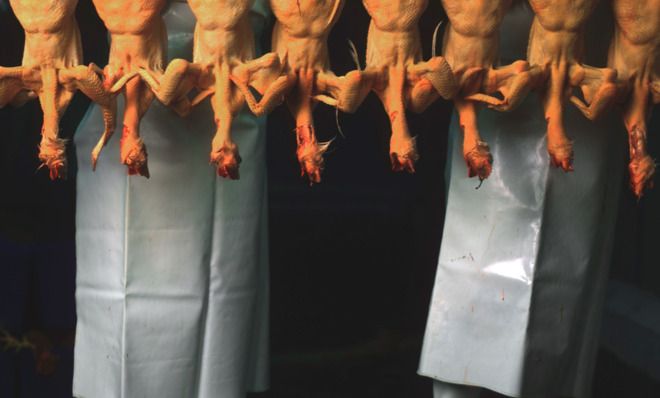

The Tyson trucks retrieve the birds six weeks later, bringing them back to the plant, where the chickens are hung upside down on hooks and decapitated before they travel down a disassembly line, where workers cut them apart by hand. The meat is battered, cooked, and frozen, then sealed inside airtight bags. The bags are loaded onto Tyson trucks and taken to grocery stores, cafeterias, hospitals, and restaurants around the country. From its conception until its consumption, the bird never travels outside of Tyson's ownership and control. The company collects every penny of profit to be made along the way because it owns every step in the process. The feed dealer or local trucker or slaughterhouse owner doesn't complain about the arrangement because he simply doesn't exist anymore. The money stays inside the system, with the surplus handed over to the company's shareholders.

(AP Photo/April L. Brown)

THERE IS ONE link in the chain that Tyson has decided not to own, one part of the rural economy that the company has pushed far outside the limits of its property. While most businesses are drawn steadily into the integrator's body, the force of gravity has been reversed when it comes to the farms. The farms are dumped from the balance sheet.

The reason for this is simple. During the 1960s, Tyson Foods realized that chicken farming was a losing game. When Tyson executives examined operations at the company, they saw that farming was the least profitable, and most risky, side of the business. When they looked to invest in the future, they decided not to invest in farms. One of the people privy to those discussions was Jim Blair, who for decades was one of the company's top attorneys.

"You need to allocate whatever capital you have where it produces the most return on your investment. Owning the land itself wasn't in that category," Blair explained. The company was more interested in the new equipment being developed for slaughterhouses. Buying just one of the big steel machines could cut out the need for hundreds of hours of labor.

"That isn't true, of course, in a 400-by-40-foot-wide chicken house. You can't crowd the chickens in. [When] there's too much chickens, you create disease and you lose efficiency. You can't keep a curve on the growth of production in the chicken house," Blair recalled.

The economics of chicken farming was stubborn, and new technology wasn't changing it. So Tyson plowed its capital into the slaughterhouses, where new dollars bought new machines that cut production time and fattened profit margins. The least profitable part of the business was left to the contract chicken farmers.

Modern chicken houses are the length of several football fields and as wide across as a gymnasium. They are wired with automatic feeders, ventilation systems, watering lines, and thermostats, all of them controlled from a centralized computer system. Each house costs hundreds of thousands of dollars to build, and acres of property are needed to dispose of the waste they produce each month. Between the industrial barns and the land, a single complex can cost north of $2 million to build. And hundreds of complexes must be in continual operation to support a single Tyson plant.

Farmers take out bank loans to finance the operations, and rural banks have become proficient at helping the farmers become indebted. The banks have learned to break down a farmer's debt payments into a schedule that perfectly coincides with the life cycle of a flock of chickens. The farmer pays the bank every six weeks or so, just when his paycheck arrives from Tyson. So with every flock, the farmer is racing against his debt, hoping the birds Tyson delivers will gain enough weight to earn a payment that will cover the mortgage and bills for electricity, heating fuel, and water.

TYSON HAS OFF-LOADED ownership to the farms, but it maintains control. The company always owns the chickens, even after it drops them off at the farm; it doesn't sell baby chicks to the farmer and buy them back when they're grown. So the farmer never owns his business's most important asset. Tyson also owns the feed the birds eat, which is mixed at the Tyson plant according to the company's recipe and then delivered to the farm on Tyson's trucks according to a schedule that Tyson dictates. Tyson dictates which medicine the birds receive to stave off disease and gain weight, and Tyson field veterinarians travel from farm to farm to check the birds' health.

Tyson also sets the prices for its birds. When the chickens arrive at the slaughterhouse, Tyson weighs them and tallies up how much it owes the farmer on a per-pound basis. When that price is determined, Tyson subtracts the value of the feed it delivered to grow the birds.

The terms and conditions of Tyson's relationship with its farmers are laid out in a contract, the single most important document for a farmer's livelihood. It ensures the steady flow of birds a farmer needs to pay off utility bills and bank debt. But for all their importance, the contracts are usually short and simple documents. While a farmer's debt is measured in decades, the contracts are often viable for a matter of weeks and signed on a flock-to-flock basis. The contracts reserve Tyson's right to cancel the arrangement at any time.

Farmers like the Yandells, who are only called "farmers" for lack of a better word, don't usually pay attention to the fine print of their contracts. They know it doesn't matter anyway. The power arrangement is set by Tyson, and the farmer learns the rules quickly enough, whatever the documents might say. Vertical integration gives companies like Tyson the kind of power that feudal lords once held.

From The Meat Racket by Christopher Leonard. ©2014 by Christopher Leonard. Reprinted by permission of Simon & Schuster, Inc.