6 reasons the U.S. should stay out of Libya

Writing in The Washington Post, Retired Gen. Wesley Clark explains why Western military involvement in Libya is a lousy idea

As the head of NATO forces in the Kosovo conflict, Retired Gen. Wesley K. Clark says he is someone who's "thought about military interventions for a long time." And as Clark writes in The Washington Post, Libya's civil war is a poor candidate for U.S. action. According to the Vietnam veteran and former presidential candidate, as much as the U.S. would like Moammar Gadhafi to fall, and democracy to flourish, "we don't need Libya to offer us a refresher course in past mistakes." Here are six of his reasons why the U.S. should stay out of Libya:

1. Intervention isn't in our self-interest

Libya doesn't sell us much oil, and it doesn't pose a direct threat to us, so there would be little national interest in our committing to fight to Gadhafi's finish. Sure, "we want to support democratic movements in the region," but America is already fighting that fight in Iraq and Afghanistan. While "it is hard to stand by as innocent people are caught up in violence," that didn't stop us from standing on the sidelines during much worse conflicts in Darfur and Rwanda.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

2. We don't have a clear objective

If we want to mount a humanitarian effort, we shouldn't involve the military, and if we want to involve the military, we need to mount a full invasion. The worst idea would be "mission creep," like our intervention in Somalia, which gradually shifted from humanitarian to military without a clear plan. And half-measures, like a no-fly zone, are just "a slick way to slide down the slope to deeper intervention."

3. We don't know who would replace Gadhafi

Even if the West ousts Gadhafi, what's the "political endgame"? The best-case scenario is a constitutional convention and multi-party democracy, but it's just as likely that "the most organized, secretive, and vicious elements [would] take over." We're in no shape to take ownership of that struggle.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

4. There's no mandate

Gadhafi's current actions, as reprehensible as they are, "aren't an attack on the United States or any other country," so under what authority would we step in? If we decide to go ahead and act without "substantial international legal and diplomatic support," like a United Nations resolution or the Arab League's blessing, we're just asking for trouble.

5. This conflict would be neither clean nor easy

The most successful U.S. interventions have been quick and as bloodless as possible, allowing us to complete the mission while keeping "our moral authority" intact. A no-fly zone in Libya might start out that way, but eventually we'd have to bomb people and send in ground troops, and as we've learned in Iraq and Afghanistan, "a few unfortunate incidents can quash public support."

6. We don't have the will to shock and awe

"We can't quite bring ourselves to say it," but involving ourselves in Libya's civil war would be yet another example of "committing our military to force regime change in a Muslim land." And our prognosis for extracting ourselves anytime soon is poor. Grenada lasted three days, Panama took three weeks, and we finished the ground fight in the 1991 Gulf War in 100 hours. But nobody is considering using that kind of "decisive force — military, economic, diplomatic and legal" — in Libya. And "the longer an operation takes, the more can go wrong."

-

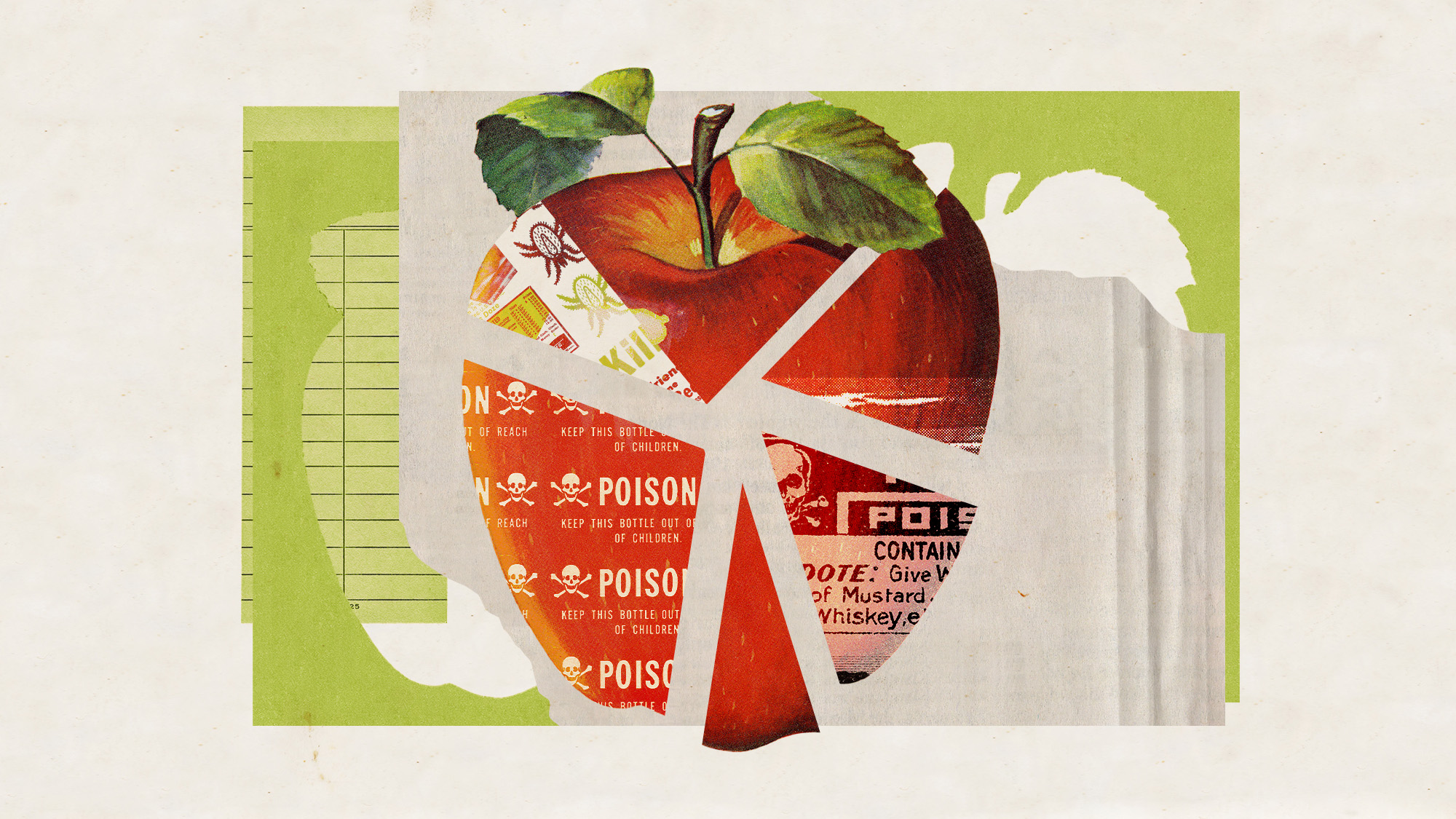

Europe’s apples are peppered with toxic pesticides

Europe’s apples are peppered with toxic pesticidesUnder the Radar Campaign groups say existing EU regulations don’t account for risk of ‘cocktail effect’

-

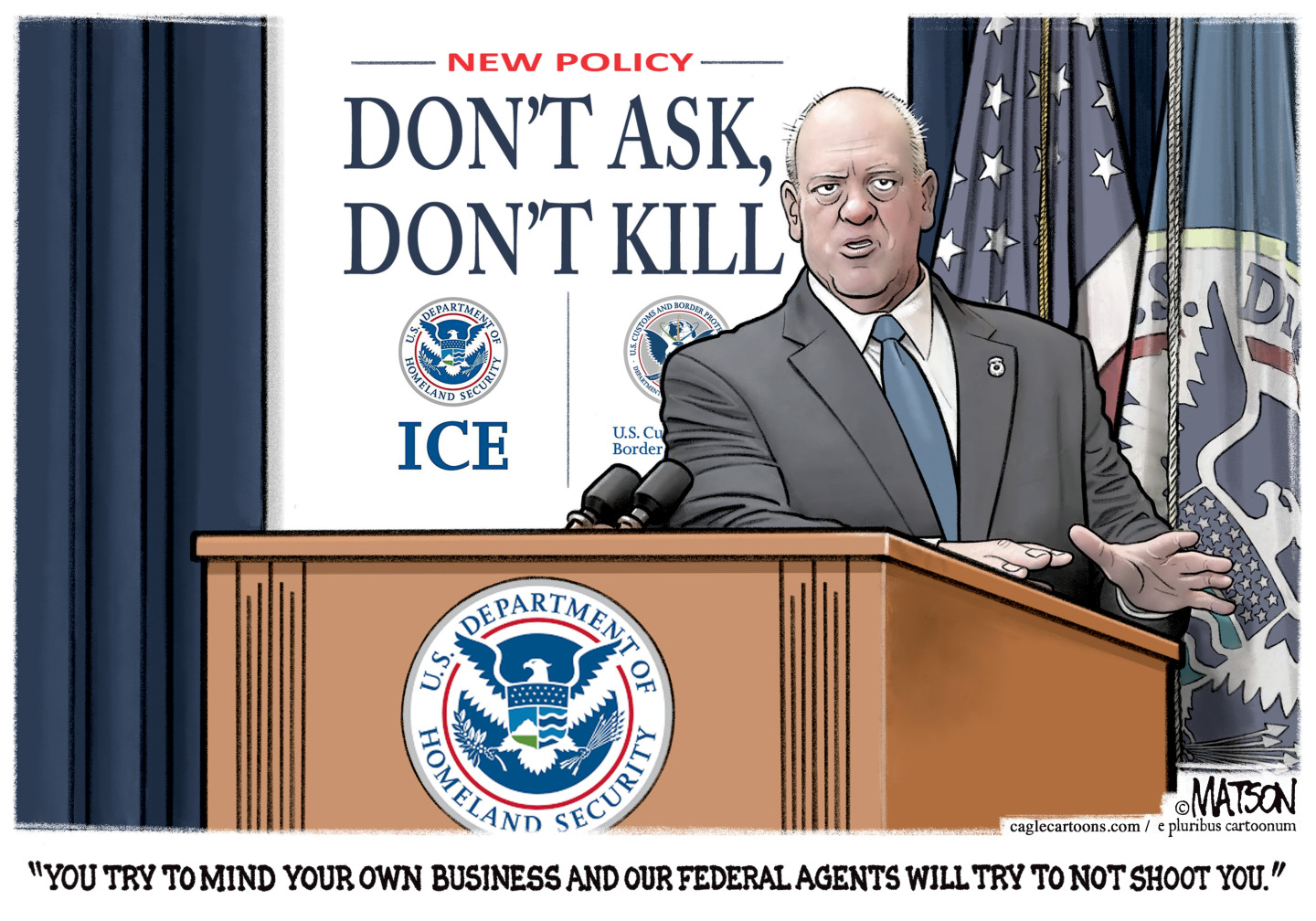

Political cartoons for February 1

Political cartoons for February 1Cartoons Sunday's political cartoons include Tom Homan's offer, the Fox News filter, and more

-

Will SpaceX, OpenAI and Anthropic make 2026 the year of mega tech listings?

Will SpaceX, OpenAI and Anthropic make 2026 the year of mega tech listings?In Depth SpaceX float may come as soon as this year, and would be the largest IPO in history