Out of work - and out of hope

With unemployment passing 10 percent and millions of jobs gone for good, the recession is taking a brutal human toll.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Who are the unemployed?

They are a very broad cross-section of the country. Some 8 million jobs have vanished since late 2007, raising the ranks of the unemployed to nearly 16 million. In typical recessions, white-collar workers accounted for about 30 percent of the unemployed; layoffs were mostly concentrated in blue-collar jobs and low-level retail positions. But in the current downturn, nearly half of the vanished jobs have been managerial, professional, and skilled white-collar positions. “The world around me just changed overnight,” says Michael Blattman, 58, a senior vice president for a student-loan company who lost his job last year. “Like East Germany: One day it was there, the next day, gone.”

Are some groups suffering more?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

As in past recessions, minorities have gotten hit the hardest. Unemployment among African-Americans is 15.5 percent, and older workers are losing their jobs at a faster rate than younger ones. Job losses are also heavily concentrated among men, whose unemployment rate is 11.9 percent, compared with 8.1 percent for women; that’s the widest workforce gender gap in post-war history. And the jobless are staying that way longer. A quarter of the unemployed have been out of a job for more than six months—the highest long-term unemployment level since the 1930s. If you factor in the people who have given up looking for work—the Labor Department calls them “discouraged workers”—and people who have settled for part-time work, the actual unemployment rate jumps to 17.5 percent. The long grind of joblessness takes a heavy human toll, reflected in elevated suicide rates in some of the hardest-hit regions of the country, as well as mounting depression and family conflicts. “You get depressed to where you don’t even want to budge,” says former construction worker Boyd Champion, 43, of Fort Myers, Fla.

Will the jobs come back?

In most cases, not the ones that were lost—and that’s another crucial difference from the past. Most recessions are considered “cyclical,” meaning they’re temporary contractions that occur when businesses produce more than the economy can absorb. In such recessions, businesses would lay off workers until demand picked up, at which point they’d start hiring again. This downturn, though, is largely structural—that is, some industries, such as housing construction, automobile manufacturing, and publishing, have apparently undergone permanent shrinkage. Kevin Martin and his family went from affluence to poverty after his home-construction business in Oregon went bust amid the housing crash, and he doesn’t foresee that industry ever returning to the boom years. “We were living the American dream,” he says. “But now we’re in survival mode, and I can’t see when that’s going to change.”

How do these people get by?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

By scraping together any income they can find, while selling off cars, eliminating vacations, and cutting expenses to the bone. At first, they receive temporary state and federal unemployment benefits—which for most workers total about 60 percent of their former pay. But unless Congress extends them, unemployment benefits run out after 26 weeks. Even with extensions, the benefits eventually expire, at which point people can apply for food stamps and welfare benefits, which can provide up to $900 per month for a family of four. But that’s often not enough to fully cover necessities such as food, housing, and health care, and people have to fall back on soup kitchens, private charities, and the help of family members. That can be devastating to those used to being self-sufficient. “I thought by this time in my life, I’d be the one peeling off a few bills for someone,” says Jan Saurbaugh, 57, who in 2007 lost his computer programming job with the Coast Guard. “I hate asking people for money.”

So how will new jobs be created?

No one really knows. Some in Congress want to ramp up spending to retain workers in shrinking industries, but that’s not a cure-all. Many displaced workers, especially older ones, have trouble learning new skills after a lifetime of experience in another field. “I’ve been a machinist since 1980,” says Gregory Przybylski, 46, of Milwaukee. “That’s all I know.” There’s been a lot of talk about how clean energy and other “green” industries will power a new economic boom. But turning that talk into reality will take years, as well as billions in private or government investment. The sad reality is that many of those who lost their jobs in the last year or two may never return to their old industries and may never again make the kinds of salaries that provide for a comfortable, middle-class lifestyle. Barring the creation of a whole new sector of the economy, says economist Rob Valletta of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, we’ll be “seeing the unemployment pool shift toward permanent job losers.”

Pretending to be employed

When Clinton Cole of Vienna, Va., lost his job at General Dynamics last February, the 40-something business-development manager could barely bring himself to tell his wife. He certainly wasn’t going to tell the neighbors. For several weeks after he was laid off, he rose at his usual time, dressed for work, and drove off in his car. For the rest of the workday, he’d read on a park bench, hang out at the library, or just walk around. That’s not unusual, says social worker Cynthia Turner, who works with the unemployed. “I have people who are laid off who still pay their country-club memberships,” she tells The Washington Post. “People are willing to talk about the stock market but not about being laid off.” Psychologists say it’s common for people to feel shame after losing their jobs, even if they’re the victims of a worldwide economic tsunami. But pretending that nothing has changed only creates more stress. When Cole finally was honest with his neighbors, they were overwhelmingly sympathetic and supportive. “If you just let them know, people will go out of their way to help you,” he says. “They think, Gosh, what if it happened to me?”

-

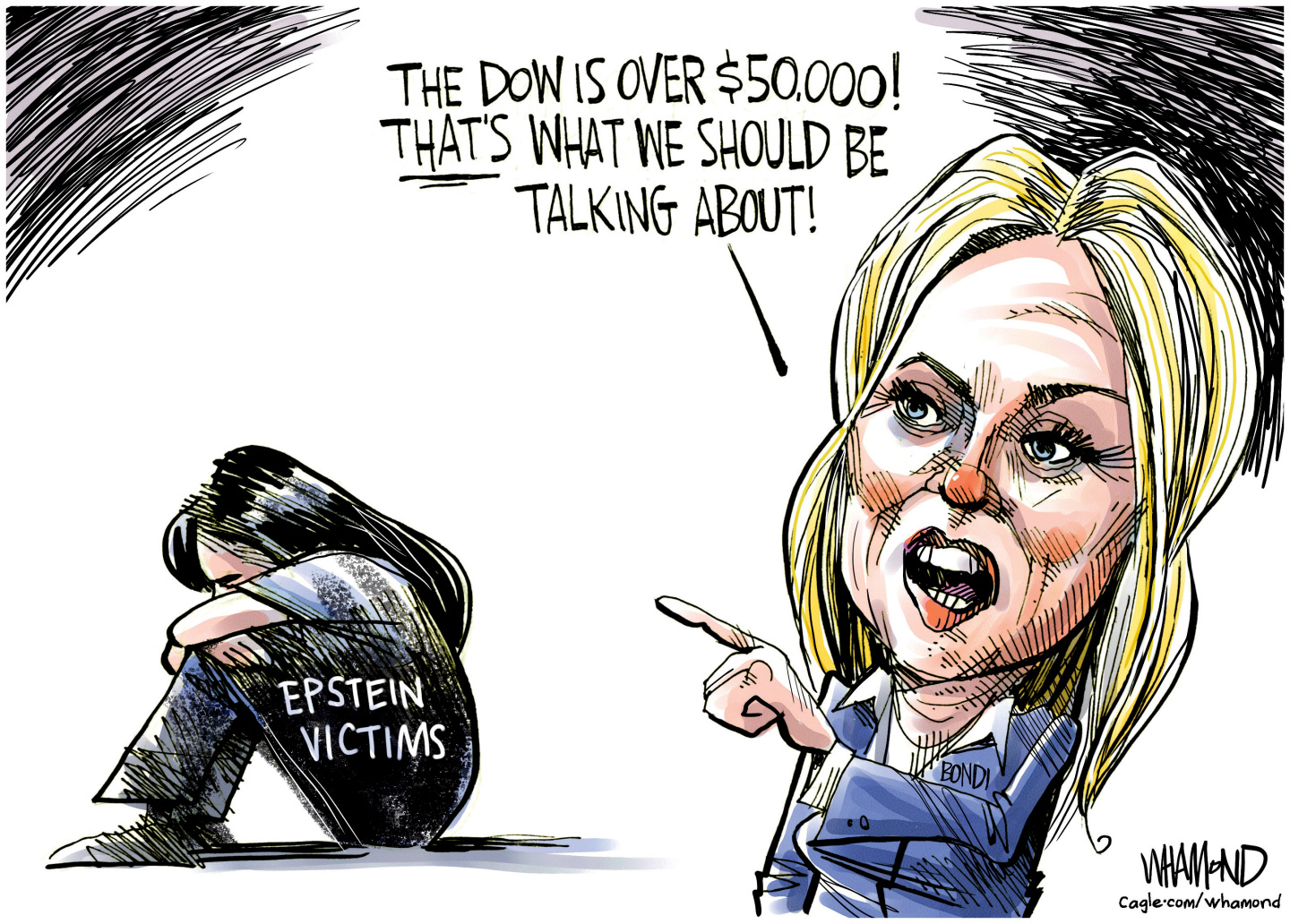

Political cartoons for February 12

Political cartoons for February 12Cartoons Thursday's political cartoons include a Pam Bondi performance, Ghislaine Maxwell on tour, and ICE detention facilities

-

Arcadia: Tom Stoppard’s ‘masterpiece’ makes a ‘triumphant’ return

Arcadia: Tom Stoppard’s ‘masterpiece’ makes a ‘triumphant’ returnThe Week Recommends Carrie Cracknell’s revival at the Old Vic ‘grips like a thriller’

-

My Father’s Shadow: a ‘magically nimble’ film

My Father’s Shadow: a ‘magically nimble’ filmThe Week Recommends Akinola Davies Jr’s touching and ‘tender’ tale of two brothers in 1990s Nigeria