Briefing: The art market: A bubble about to burst?

How well has art been selling? The past decade has seen an unprecedented boom in the international art market, reaching a climax in the last two years. Sotheby

The housing market and Wall Street may be in trouble, but the contemporary art market has stayed remarkably strong. Is art really immune from the economic downturn?

How well has art been selling?

The past decade has seen an unprecedented boom in the international art market, reaching a climax in the last two years. Sotheby’s and Christie’s, the two main auction houses, together sold an eye-popping $12.5 billion in artwork last year—an annual increase of more than 40 percent. All sorts of records have been smashed: Mark Rothko’s White Center sold for $72.8 million, doubling the top price for a postwar work; and the world auction record for a work by a living artist was set by Jeff Koons’ Hanging Heart, at $23.5 million. Even this year, despite repeated predictions of imminent collapse, bidding has remained frantic: Francis Bacon’s Triptych 1974–1977 sold for $46.1 million in February, the highest price ever paid for a postwar work in Europe. Then, two weeks ago, Lucian Freud broke Koons’ record for a living artist when his nude portrait Benefits Supervisor Sleeping sold in New York for $33.6 million.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

So are all art prices surging?

No. From June 2006 to June 2007, old masters increased in value by just 7.6 percent, according to an industry report, while British 17th- to 19th-century portraits and watercolors actually declined in value, by 7.5 percent and 27.5 percent, respectively. The big boom is in the prices of modern art (defined as art produced from the late 19th century to the 1970s), which jumped 44 percent, and of contemporary art, which soared 55 percent. The enthusiasm for contemporary works is so fevered that it affects not just the Lucian Freuds and Francis Bacons but also less proven artists. And the Chinese and Russian markets are really going crazy. Between 2005 and 2006 the value of contemporary art sales in China increased by 983 percent.

Who is buying all this art?

In the 1980s, the principal buyers of contemporary art were private companies that bought it not as an investment but to beautify their offices. The current boom has been driven by new money—hedge-fund managers, CEOs, oil magnates, pop stars, models, and actors. Prices have also been boosted by Middle Eastern buyers, and by newly minted Russian and Chinese tycoons. Buoyed by booming energy prices, the Russian art market rose an incredible 2,365 percent between 2000 and 2005. Sotheby’s now includes Russian rubles in its electronic listing of currency conversions.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Are these works worth these crazy prices?

It’s hard to say. Art isn’t like a stock or bond, with a calculable value. Each piece is simply worth what you can persuade someone else to pay for it. And that depends on fashion, the availability of cash, and how many people turn up at auction. Like a Gucci bag or a professional sports franchise, art is an aspirational “trophy” product—the super-rich compete fiercely for what they call “wall power” for their homes and offices. Many traditionalists, such as veteran New York art dealer Richard Feigen, would argue that works by the likes of Koons and Damien Hirst “have no place in the history of art.” He complains that their value is dictated by the “mafia” of the art world—dealers and curators who lead the gullible rich into paying absurd prices. Even so, contemporary art is often a profitable investment. Advertising mogul Charles Saatchi bought Hirst’s embalmed shark for $98,925 in 1991 and sold it in 2005 for more than $12 million. Still, it’s a risky business: A glance at the catalogues from 10 years ago shows that around half of the contemporary artists in them are no longer sold at top auctions.

So will the bubble burst?

Some insiders say that falling house prices, big bank write-offs, and smaller Wall Street bonuses may indeed burst the bubble. Conventional wisdom says that the art market goes flat six months to two years after the broader economy slows down. “It can’t and won’t go on,” warned The Economist a few months ago. And certainly, art bubbles have burst before. After a decade of massive price inflation came the great art bust of 1990. Prices crashed by 25 percent to 75 percent, and didn’t recover for five years. But the many predictions of imminent doom have so far proved wide of the mark. Indeed, some analysts predict that the current boom will continue for years.

What makes them so confident?

The world has changed since 1990. Back then, many art buyers were from New York and London, and so were greatly affected by the stock market crash. These days, Russian, Asian, and Middle Eastern buyers—who sit atop growing mountains of petro-dollars or manufacturing wealth—are much less rocked by fluctuations in the Western financial sector. Philip Hoffman, who set up the first hedge fund devoted to art investment, says he has clients from all over the world spending huge amounts of money. “They are completely oblivious to the credit crunch,” he said. “In the long term the art market is a one-way street.” For the first time since 1914, claims Tobias Meyer, Sotheby’s world head of contemporary art, “we are in a non-cyclical market.” We may soon find out whether this is wishful thinking.

A market where anything goes

The contemporary art market is not like other markets: Almost totally unregulated, it is largely controlled by the auctioneers and the dealers. The “superstar” dealers who manage many of the hottest artists do not sell their work—they “place” it. Novice collectors have to be patient, presenting their credentials and explaining what they intend to do with the art—dealers don’t want it “flipped at auction” too soon. But dealers will grant discounts in order to place work with an “important” collector. Museums get an even larger discount: “Museum-quality” is the ultimate accolade, greatly boosting an artist’s prices. Prices are carefully managed—some might say manipulated. Charles Saatchi is said to have limited the output of artists he patronizes. When Hirst’s diamond-encrusted skull, For the Love of God, sold last year for $98.9 million in a private sale, it was touted as a record for a work by a living artist, enhancing the value of all Hirst’s work. Closer inspection revealed that Hirst himself retained a 24 percent stake in it; many in the art world think he never sold it at all. The New York Times once accused Hirst of being less an artist than “the manager of the hedge fund of Damien Hirst’s art.” But as Andy Warhol once observed: “Good business is the best art.”

-

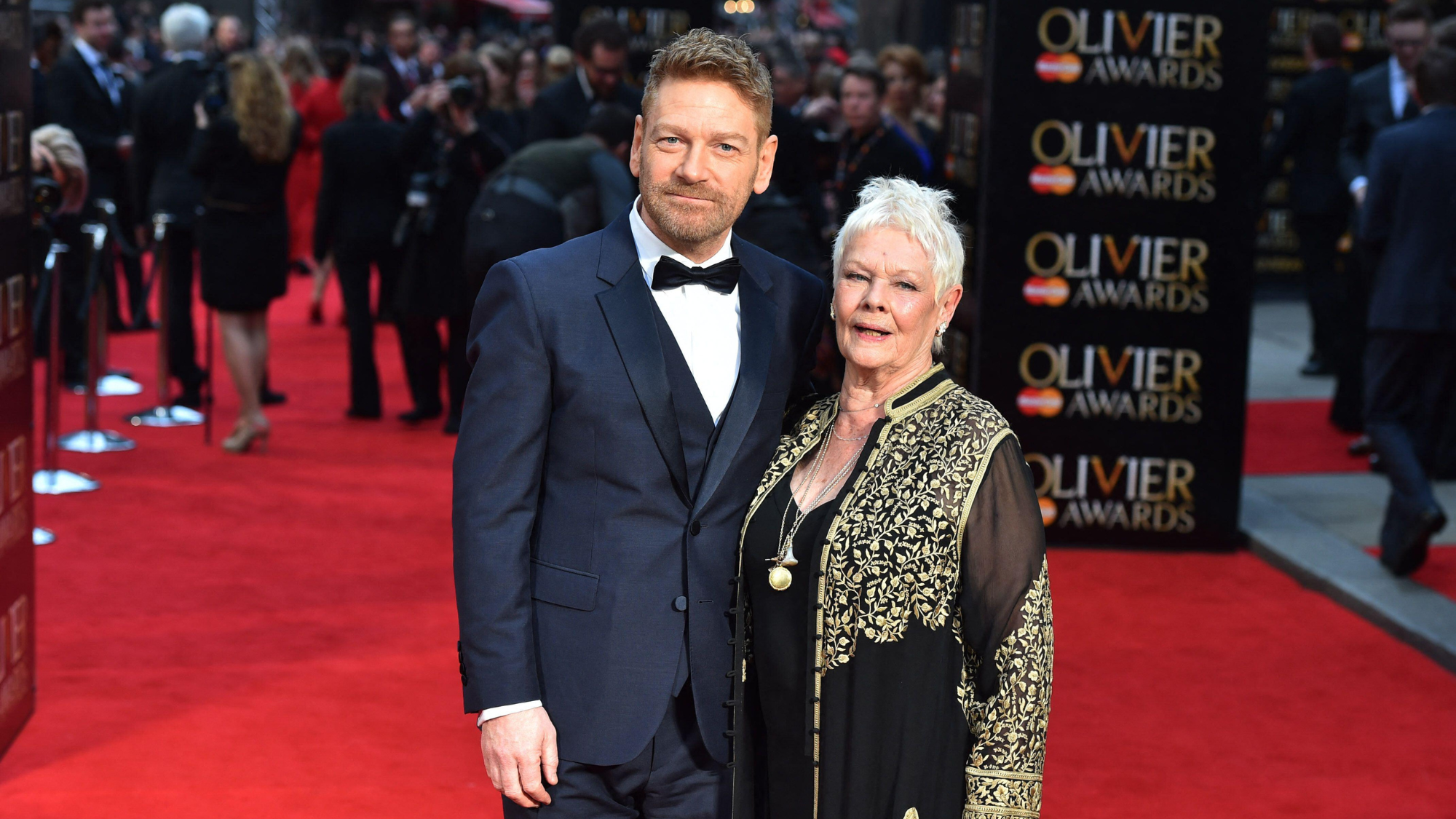

Tea with Judi Dench: ‘touching’ show is must-watch Christmas TV

Tea with Judi Dench: ‘touching’ show is must-watch Christmas TVThe Week Recommends The national treasure sits down with Kenneth Branagh at her country home for a heartwarming ‘natter’

-

Codeword: December 24, 2025

Codeword: December 24, 2025The daily codeword puzzle from The Week

-

Sudoku medium: December 24, 2025

Sudoku medium: December 24, 2025The daily medium sudoku puzzle from The Week