What a successful university mental health program looks like

American colleges have a mental health problem. Here's how to fix it.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

On May 20, Karen Arkin was standing in the common room of her son's dormitory at Northwestern University. The day before, in the early morning hours, Jason Arkin went into that room and took an overdose of pills that sent him into a seizure. He was taken to a local hospital, where he died that afternoon.

Now, as Arkin stood in the same room where her son had taken his own life just hours earlier, she was being asked by a university administrator to hide what had happened. (Citing federal law and university policy, Northwestern declined to comment to The Week on Arkin's case.)

The administrator, as Arkin recalls, said, "'As far as all the students know here, he just had a seizure. So they can just think he died of a medical condition.' I said, 'Absolutely not. The students are going to know, one way or another, that this was a suicide. They deserve to know.'"

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The National Center for Education Statistics estimates that more than 20 million students will attend American colleges or universities this fall. The National Alliance on Mental Illness says that one in four adults aged 18 to 24 — in other words, college-aged — are living with some form of mental illness. That suggests that millions of students arrived on college campuses this fall with a mental illness. And given that symptoms of mental illness tend to coalesce for the very first time during young adulthood, these students may be arriving with an as-yet-undiagnosed condition.

Consider for a moment what attending a university means for an 18-year-old. You're uprooted from the comfortable social network you've grown up in. You're suddenly given a surfeit of freedom that you often don't know how to deal with. You're thrust into a brand-new pressure-cooker environment, where the stresses of making new friends and handling new academic challenges are mixed in an often-combustible way. Everything is new. Plenty of the new things are hard.

This leads to no shortage of tragic stories, like that of University of Pennsylvania freshman Madison Holleran, who was by all accounts smart and successful, and who took her own life last January. There are schools like Northwestern — my alma mater, and a place I love — which saw two suicides in five days, and seven in just five years. The list goes on.

The psychiatry bible DSM-5 says mental disorders are "usually associated with significant distress in social, occupational, or other important activities." That's exactly what college is for many students. Is it any wonder so many young adults struggle with mental illness, and that far too many resort to suicide?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The question shouldn't be why so many young American adults struggle with mental illness. The real question ought to be why colleges aren't doing a better job of helping them.

Colleges' mental health programs are often faulted for a variety of shortcomings: absurd wait times to see a school counselor, limited availability of free counseling sessions, forcing medical leave on a student against her wishes, and making it hard for a student with a documented mental health struggle to re-enroll.

At the same time, the benefits of a college degree are at an all-time high. In a sluggishly recovering economy, receiving some form of higher education is now all but mandatory to get ahead. College seems simultaneously more necessary and more dangerous than ever. So how can universities cope?

There is no single answer to this question. It takes a confluence of factors for a school to create a successful mental health program: a comprehensive strategy, financially accessible care options, and a thoughtful campus culture around mental health.

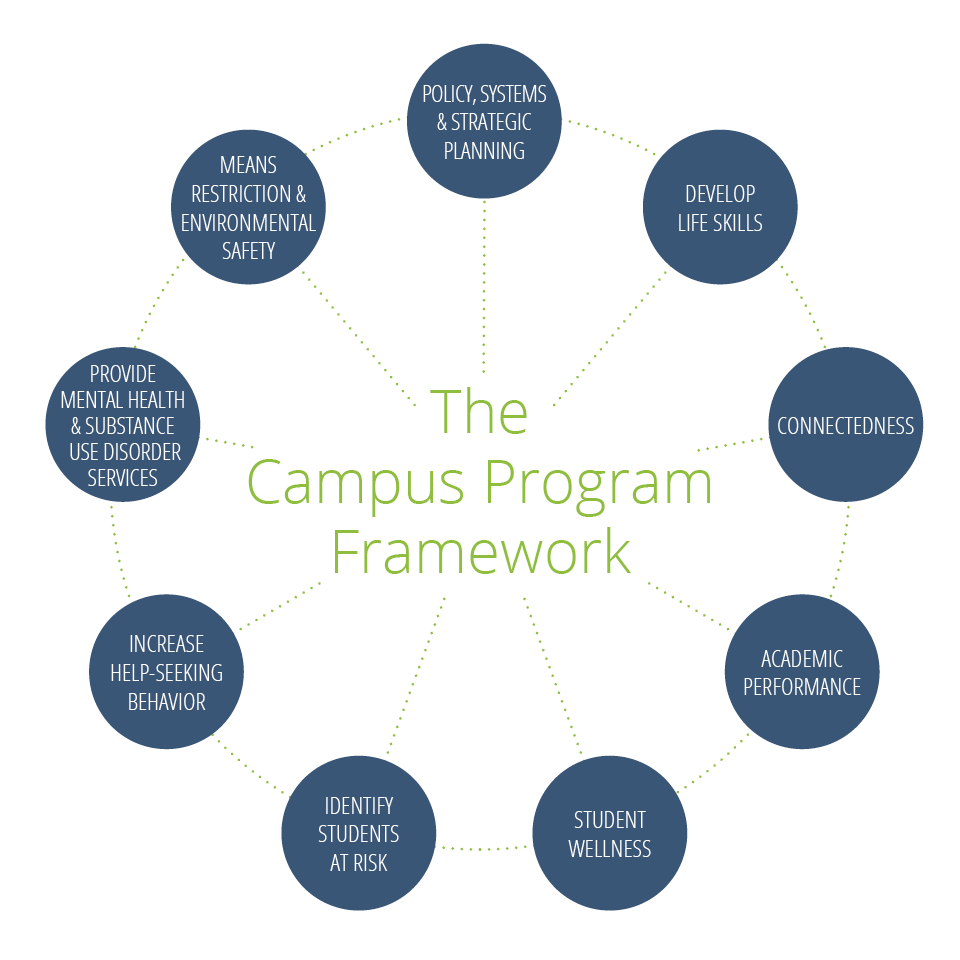

There are two major arms to mental health programming: prevention and treatment. But separating the two is easier said than done. The Jed Foundation, an organization dedicated to mental health promotion among college students, has outlined this framework for university mental health programs as part of its Jed and Clinton Health Matters Campus Program:

As the graphic shows, there is an interconnected web of factors that go into promoting student wellness. It's about more than addressing the tragedies, says Dr. Victor Schwartz, medical director of The Jed Foundation. "As a starting point, schools need to have good clinical services and services that can address a crisis… but [it] goes way beyond that," he says. Schools must help their students build life skills, like time management, basic health and nutrition, and sleep scheduling. Then comes teaching students when to reach out for help, either for themselves or on behalf of a friend.

At the University of West Georgia, this is done through collaboration. The counseling center joins with peer mentors, creating an indirect peer-to-peer outreach arm; students work with academic advisers who often direct students to counselors; those counselors intervene in substance-related or other physical health scenarios; and so the circle goes. "Our approach is not only to suicide prevention but just towards mental health, really," says Dr. Lisa Adams, director of the university's counseling center. "Sometimes, the focus gets shifted really heavily toward suicide prevention, and that can cause students who say, 'Well, that's not my thing,' to not even pay attention. But everybody has anxiety and stress. Lots of us feel depressed from time to time."

In 2013, the University of West Georgia was awarded with a campus "seal" by The Jed Foundation in recognition of its comprehensive mental health programming. The other recipients of the seal were, for the most part, large and prestigious urban universities or small and renowned liberal arts colleges. UWG is a rural NCAA Division II school located at the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains in tiny Carrollton, Georgia. Adams says about 5,000 students — more than 40 percent of the university's entire enrollment — attended at least one event hosted by the counseling center over the last academic year. Meanwhile, the school has six dedicated counselors on staff, each of whom serves roughly 30 to 40 students. That's more than 200 students who seek counseling on a regular basis.

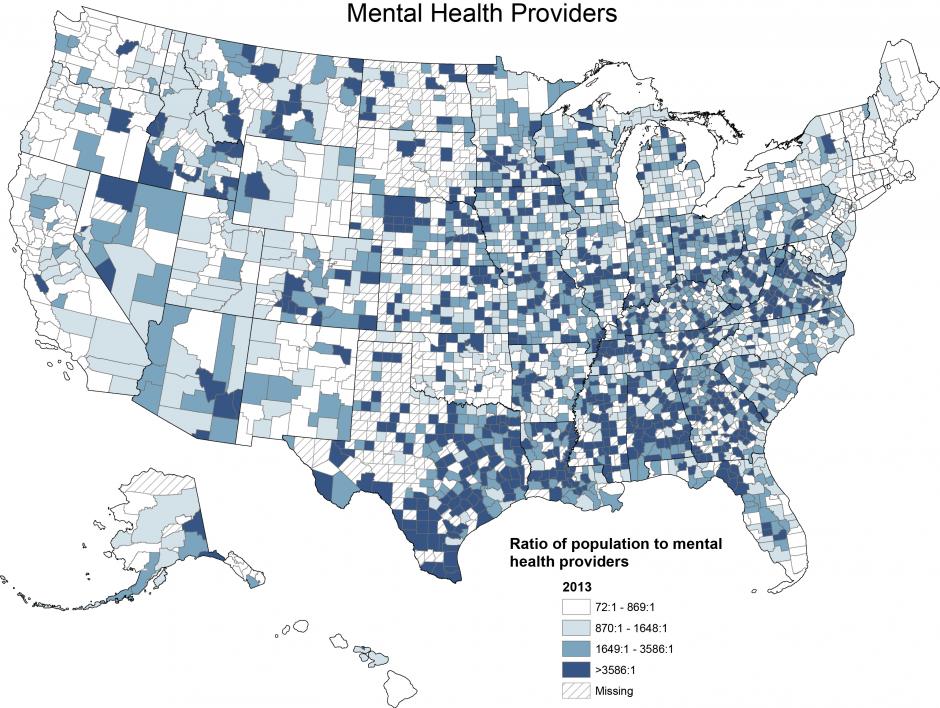

In March 2014, Newsweek published a series of maps meant to illustrate relative health by county across the nation, using data from the County Health Rankings. One showed the stark difference in access to mental health providers in different regions of the U.S.:

As the map makes clear, residents of the South are at an extreme disadvantage compared to their Western or Northeastern counterparts. UWG is acutely aware of this; where other schools may be able to rely more on referrals when it comes to clinical treatment, UWG has to provide more in-house care if it wants to serve its students effectively. That's one reason there are no counseling session limits for UWG students, and services are built into tuition and thus free of additional charge. (A grant first allowed UWG to offer this premium level of service.)

Money, of course, is a huge issue here. Maybe some students in urban schools can afford the costs of private therapy when session limits are imposed; others can't. Insurance billing can be a headache. Skyrocketing tuition costs are already a source of national disdain, but leaving fees like mental health counseling off the annual number means charging more for them in the moment of need. How much responsibility do universities really have to providing such services to students, especially as they affect the bottom line?

Zero, says Schwartz of The Jed Foundation. No level of government has created a legal mandate demanding that schools provide mental health services.

Still, there can be a financial benefit to universities that spend money on these services: They stand a better chance of keeping students struggling with mental health in school, and thus not losing their tuition. Schwartz, who spent time as the medical director of the counseling center at New York University, says keeping two students enrolled at NYU could generally pay for one counselor.

There's a whole body of research to support this, pioneered mostly by Daniel Eisenberg, an associate professor at the University of Michigan. In 2013, The Healthy Minds Network (of which Eisenberg is the director) published a research brief acknowledging that schools might have a hard time quantifying the value of mental health services compared to, say, research revenue or patents filed.

Consider a hypothetical initiative that would provide mental health care for 500 depressed college students in a year (e.g., hiring a handful of new clinicians at a counseling center or health clinic). Based on our analysis… we estimate that this hypothetical program would yield approximately $1 million in additional tuition revenue (assuming a rate of $20,000 per student-year) and over $2 million in lifetime economic productivity for the students. By comparison, the cost of providing mental health care for 500 depressed students would be no more than $500,000. [The Healthy Minds Network]

"The argument starts with why mental health can affect academic performance, by affecting concentration, optimism about the future, energy, sleep, and so on," Eisenberg told The Week in an email. "Depression predicts a doubling in the likelihood of leaving an institution without graduating," which, in cold hard terms, not only robs the school of that student's tuition money, but also of a promising young alumnus to add to its network.

That said, there's a big difference between having mental health services and actually getting students to use them. For a student like Northwestern's Jason Arkin, described by his mother as a "perfectionist," taking time away from his studies to attend counseling seemed like a bad tradeoff. (His mother partially attributes this to the rigorous non-inflationary grading practices of Northwestern's school of engineering, of which Jason was a student.)

The first time Jason interacted with Northwestern's Counseling and Psychological Services office, his mother says, was as a freshman in late November 2012, when he called the office at his mother's urging. "He said, 'They told me I sound like I have a lot of problems and I need to go private practice,'" Arkin says. Immediately, Arkin started searching for resources in the area and tried to make her son an appointment with a local hospital. But because Jason was 18 years old at the time and legally an adult, Arkin was told she couldn't make an appointment on his behalf. Jason would have to call himself.

Because this happened right before Jason's first round of finals, Arkin knew Jason wouldn't make himself an appointment and keep it, and especially not if it was off-campus. She says Jason was referred to private practice because Northwestern had a wait list and couldn't accommodate him, and there was no way for her to facilitate through the university a way to ensure Jason sought help. He never interacted in-person with any school doctor, and his only subsequent contact with the department was two phone calls the school's counselors made to him, in December 2012 and January 2013, which went unanswered. After that, Northwestern closed Jason's file.

Alan Cubbage, Northwestern's vice president of university relations and its chief spokesman, declined to comment on Arkin's case, but wrote the following in an email to The Week regarding the school's mental health resources:

Northwestern's Counseling and Psychological Services provides a wide range of mental health services to full-time students at no charge, including clinical services, educational workshops, and consultation. In addition, the University provides stress management clinics, success strategies workshops, and other resources to assist students. The University at all times strives to provide a safe, welcoming and supportive environment for all Northwestern students, faculty, and staff.

Still, it seems like Jason fell through the cracks. Why does this happen to students in need? Perhaps due to the stigma of reporting a problem and seeking help. This is something schools must actively work to combat, says Steve Arkin, Jason's father. "They should understand this is a transition point: being at school where your neighbors were all in the top 1 or 2 percent of their high school classes. The stigma of speaking out and saying, 'Hey, I'm not like these people anymore,' is a huge step in the wrong direction in most students' minds, so they're not going to admit to it."

That's where an organization like Active Minds comes in. (Northwestern does have an Active Minds chapter, and it is also a member of the Jed and Clinton Health Matters Campus Program.) A nonprofit dedicated to empowering students on the topic of mental health, Active Minds trains student members to discuss mental health through peer-to-peer outreach. "The heart of our mission is changing the conversation about mental health," says Sara Abelson, vice president for student health and wellness at Active Minds.

For students to productively talk about mental health, they have to know what that means in the broader sense, rather than just the buzzwords of diagnosis, counseling, and medication. And just like the University of West Georgia trains its faculty to recognize when a student might be in need, Active Minds trains students to recognize signs in their friends and peers. "When students are struggling, they're much more likely to go to a friend before they go anywhere else," Abelson says. "We help our students understand the line of doing outreach, doing education, doing advocacy — and help them see the value of serving as a referral and working to connect students as needed to those clinical resources."

Of course, Active Minds' focus on "changing the conversation" about mental health on a given campus assumes there is an existing conversation to change. But the challenges of confidentiality and stigma remain huge. While many student members join Active Minds because of their personal experiences with mental health, some don't, and there's no expectation that members share their personal stories to galvanize discussion. Instead, a chapter can avail itself of the Active Minds Speakers Bureau program, which brings volunteers to campuses to speak about their mental health experiences and help break the ice. This way, an Active Minds chapter can start the conversation on campus without forcing its student members to speak publicly about touchy issues and expose themselves to criticism.

Still, Karen Arkin confronted the consequences of what she views to be a flawed mental health culture at Northwestern when she was asked by the university administrator to "whitewash" the cause of her son's death. "I didn't feel that we had to hide this," Arkin says. "We had to honor our son's struggle and respect his pain and let other students know, 'You're not alone if you're feeling this way.'"

The high school class of 2016 includes 3.2 million students who are in line to explore colleges this fall and choose one next spring. How should they assess a prospective school's mental health culture?

Evidence of effort toward the cause, such as an operating Active Minds or NAMI on Campus chapter, or membership in The Jed Foundation's Jed and Clinton Health Matters Campus program, is a good start. While Schwartz notes that there is no U.S. News and World Report-style ranking of schools excelling in mental health programming, he did cite Cornell University, the University of Texas at Austin, and the University of Minnesota as schools that are, anecdotally, doing good work in this realm. Active Minds just released its own list of "Healthy Campus Award" winners, which includes those same three schools as well as the University of North Carolina at Greensboro and Western Washington University.

Sometimes, an indication of a generally healthy mental health program can be as simple as how a school publicizes its offerings. Is there a dedicated website for health services, counseling services, or disabilities services? Do they look like undervalued offshoots of the school's main online presence, or are they an integrated part of the system? Are they easy to find or hidden beneath tab after tab of site navigation? Are there only two listed counselors for a school of 20,000 students? (Schwartz says the generally appropriate metric is one counselor per 1,000 students.) For its part, UWG's counseling center has a dedicated website, and Adams says her team emphasizes social media outreach because "that's where students are."

Where the students also are, a majority of the time, is in their dorm rooms, a setting the Arkins feel could be crucial in preventative measures. In particular, Steve Arkin says, resident advisers could be key members of the mental health team if given the proper agency. Resident advisers "should be notified of who on their dorm floor is at high risk based on their behavior or based on phone calls to [counseling services]," Arkin says. "They should have protocol for talking above their level, to administration, to say, 'This boy's parents reached out to me.'"

And there's always the question of what the policies that do exist actually mean. Something both Schwartz and Abelson specified as a good litmus test is whether there's parity between a school's mental and physical health policies. "One of the main things that we've come to do more and more is talk about mental health as a piece of a continuum, just like physical health is," Schwartz says. "Rather than focusing on diagnosable conditions... we're trying to create a mode of communication that really addresses feelings and experiences."

Leave of absence policies are a crucial piece of the puzzle, as strict rules can become a barrier to students seeking help early if they feel they'll be forced to take medical leave or that they may have a hard time re-enrolling down the line. If the policy for mental health lines up with the policy for physical health, that worry can be assuaged. "Sometimes students do need to take time and seek treatment," Abelson says. "That's not a bad thing. It's just about figuring out how the policy can most support students making the right decision for themselves."

Every student has different needs. Some students with prior diagnoses may need more clinical support, while others who feel they are stress- or anxiety-prone may be more focused on the preventative initiatives of a school. For a student like Jason Arkin, understanding a school's grading policy and how that could intersect with personal pressures might be an important factor. Others still may just be interested in knowing their college is working toward promoting and treating mental health issues. Existing evidence of either established mental health programming, or of work toward the cause, is key.

While the Arkins say they're not planning any litigation against Northwestern (something they also stated to The Daily Northwestern back in June), they hope the school will overhaul its approach to mental health. "There was so much support and anger and outrage from the student population" after Jason's story was reported, Steve Arkin says. He hopes they can do something, anything, "to try to figure out a way to make Northwestern and all schools a safer environment to nurture and protect their students."

That, the bereaved father says, is how you "save somebody in the future."

Kimberly Alters is the news editor at TheWeek.com. She is a graduate of the Medill School of Journalism at Northwestern University.

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day