How Disney's new Jungle Book corrects for years of troubling racial undertones

Finally, a refreshing attempt to modernize Rudyard Kipling's beloved novel

If mention of The Jungle Book conjures up warm childhood memories of singing bears and dancing monkeys, Disney's new star-studded, live-action/CGI version, which hits theaters Friday, will delight you. But beyond the sheer aesthetic pleasure of Baloo and King Louie cavorting around on the big screen again, the new film is a surprisingly thoughtful attempt to modernize Rudyard Kipling's 1894 novel, and the troubling racial underpinnings on which it's built.

Each version of The Jungle Book begins the same way, as Mowgli, an orphan boy raised by animals in the jungle, is pushed to return to humankind by his animal caretakers. "This is my home!" Mowgli cries out in protest when Bagheera, the wise panther, tells him he must return to the "man village" to elude the attention of Shere Khan, a man-eating tiger.

This conflict is the essential heart of The Jungle Book story, and appears in every telling. In each version, Bagheera insists Mowgli belongs back with the humans, and in each version, Mowgli refuses to return. For more than a century, The Jungle Book has resonated with audiences as the story of a boy's struggle with seemingly incompatible cultures. But it's how each version casts this struggle that reveals the most about the period in which it was made.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Mowgli's rejection of humankind eventually leads him to a group of monkeys who want to exploit his unique capabilities as a human for themselves. Over the years, this use of the monkeys in the story has drawn the most criticism. Black and brown people have a long and unsettling history of being portrayed as monkeys, and Kipling's novel readily utilizes that stereotype.

Walt Disney and his team took a different, though similarly misconceived, approach to the monkeys in the 1967 animated film. The monkeys' orangutan leader King Louie was named after the African-American singer Louis Armstrong (though voiced by Louis Prima, an Italian-American). The implications here are insidious. When Mowgli refuses to help them, Louie and the monkeys become "casually violent" before ultimately "destroying what's left of their home," says the scholar Greg Metcalf, arguing that the parallels to the 1960s Civil Rights Movement — and specifically the Watts Riots, which occurred during the production of The Jungle Book — are "too obvious to ignore."

The catchy song "I Want to Be Like You," as performed by King Louie, draws another association entirely. The subtext unintentionally gives voice to a greater real-world struggle by playing into a phenomenon described by Frantz Fanon, a black French philosopher who argued that black people who no longer identify with their cultural origin embrace the culture of their colonizers by trying to appropriate and imitate it. Louie, the self-described "king of the jungle," has "reached the top" of his own society, and now wants to imitate a superior one. For anyone who recognizes the Louis Armstrong caricature, the implication is troubling.

These inherent flaws might make The Jungle Book seem like a daunting prospect for modern-day audiences, but the new version isn't just another adaptation. It's a thoughtful modernization. King Louie, now played by Christopher Walken, is no longer an orangutan (which aren't even native to India), but a Gigantopithecus, an extinct ape that was endemic to the area. And while Louie still sings "I Want to Be Like You," the lyrics are altered so it's clear that Louie believes the relationship is one that would benefit Mowgli as much as it benefits himself.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

But the most pivotal change in this new version of The Jungle Book comes in the ending. Kipling's novel ended on a note of melancholy; Mowgli returns to the man village, but doesn't quite feel at home, and is quickly cast out for killing Shere Khan. Rejected by both animal and man, Mowgli is left to roam the jungle independently as neither. Disney's 1967 animated feature rejects that ending entirely by implying that Mowgli, deep down, belonged with his fellow men after all. As he leaves his animal friends behind, the film dispenses with the idea of assimilation, arguing instead for a kind of cultural segregation.

Nearly 50 years later, this new Jungle Book comes from a different Disney — one whose more recent animated films, including Frozen and Zootopia, have a distinctive bend toward progressivism. The new Jungle Book firmly dismisses the idea that Mowgli would end the tale as a man without a country, or entirely reject his life in the jungle. "This is my home!" Mowgli yells, once again, in his climactic confrontation with Shere Khan. But this time, it's no longer a vain protest; it's a declaration of belonging precisely where he chooses.

-

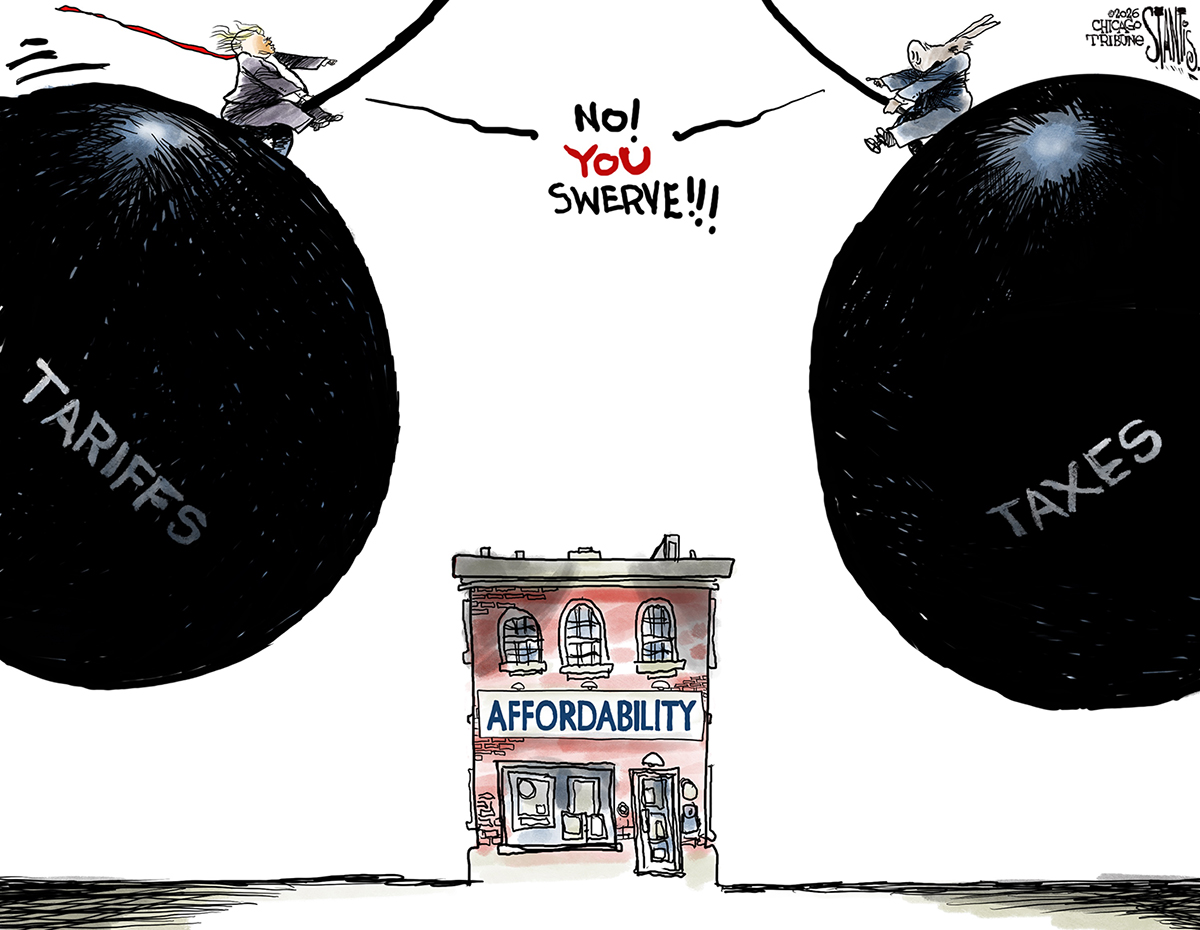

Political cartoons for January 18

Political cartoons for January 18Cartoons Sunday’s political cartoons include cost of living, endless supply of greed, and more

-

Exploring ancient forests on three continents

Exploring ancient forests on three continentsThe Week Recommends Reconnecting with historic nature across the world

-

How oil tankers have been weaponised

How oil tankers have been weaponisedThe Explainer The seizure of a Russian tanker in the Atlantic last week has drawn attention to the country’s clandestine shipping network