A pioneering black photographer comes home

A new exhibition at Boston's Museum of Fine Arts showcases a career-defining project from iconic photographer Gordon Parks

In 1950, LIFE magazine sent photographer Gordon Parks to his hometown of Fort Scott, Kansas, to shoot a story on the impact of school segregation. But Parks' camera lens focused on a much more personal story — the photos of which have rarely been seen.

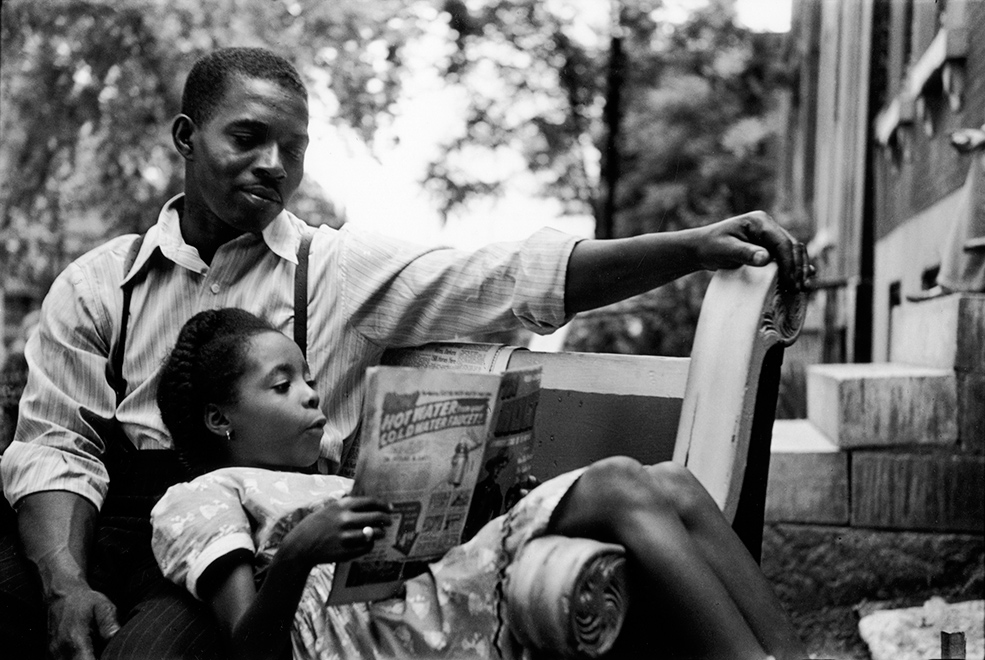

Untitled, Fort Scott, Kansas. Gordon Parks | (Courtesy and copyright The Gordon Parks Foundation, Courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.)

Parks (1912-2006) was the first black photographer hired by LIFE, and he used this distinction to tell previously untold stories, capturing moments many LIFE readers wouldn't otherwise see. It was this perspective that became the backbone of a photo essay, "Back to Fort Scott," that he shot in his hometown.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

LIFE magazine never published those images; pressing news apparently kept pushing the story back, until the photographs slowly disappeared into Parks' now-legendary portfolio. Luckily, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, has collaborated with the Gordon Parks Foundation to resurrect this impressive early work.

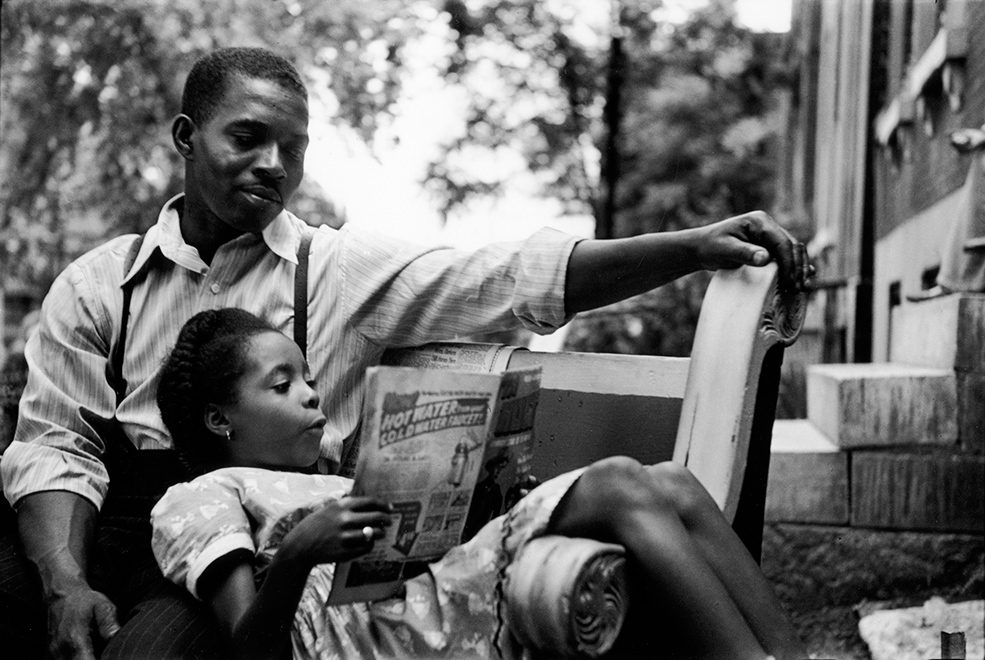

The photographs in Gordon Parks: Back to Fort Scott, which opens January 17, offer a glimpse into Parks' past, as well as life for blacks in the small town situated near the Kansas-Missouri border — a neighbor sits idly on her porch, little black girls stand behind the crowd watching a white baseball game, and Uncle James rests on a bench.

"I loved the idea that he had only been working as a photographer for about a year and a half at this point, and yet he's assigned this story, and he makes it his own," says MFA's Lane Curator of Photographs Karen Haas. "He looks at this national issue, through the lens of his own childhood…It was about mining his own story."

Mrs. Jefferson, Fort Scott, Kansas. Gordon Parks | (Courtesy and copyright The Gordon Parks Foundation, Courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.)

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Untitled, Fort Scott, Kansas. Gordon Parks | (Courtesy and copyright The Gordon Parks Foundation, Courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.)

Uncle James Parks, Fort Scott, Kansas. Gordon Parks | (Courtesy and copyright The Gordon Parks Foundation, Courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.)

Parks discovered during his homecoming that most of his black classmates had headed north as part of the Great Migration, in search of something more. And this fact planted a seed in the photographer, which really began to bloom after he left Fort Scott.

"This project feels like it allowed him to go back and take stock of where he was, where he'd come from," Haas says. "It's as though (this project) opened the floodgates and allowed him to do everything that came after — from composing music to writing poetry to his decision to be buried (in Fort Scott) when he died. I think this is where it all starts."

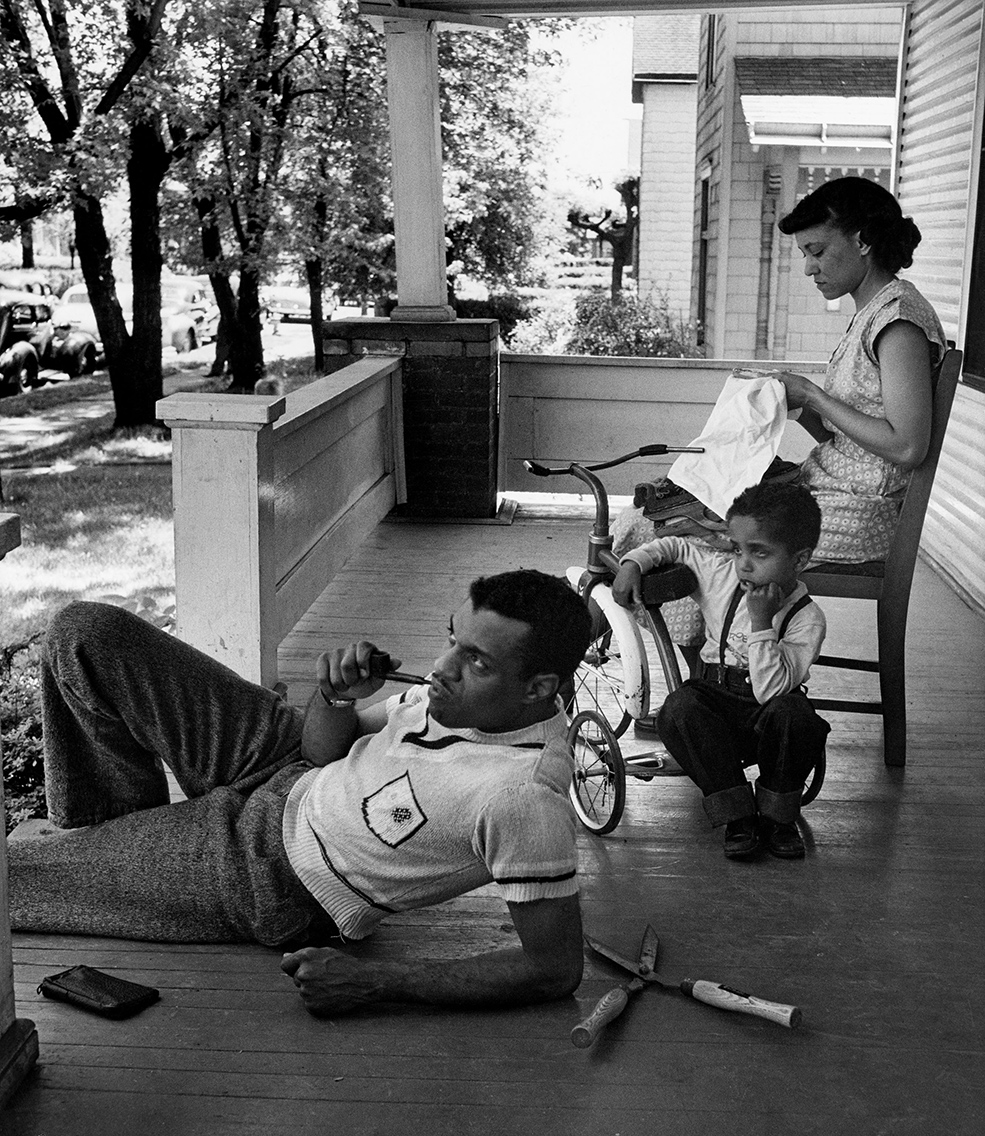

Husband and Wife, Sunday Morning, Detroit, Michigan. Gordon Parks | (Courtesy and copyright The Gordon Parks Foundation, Courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.)

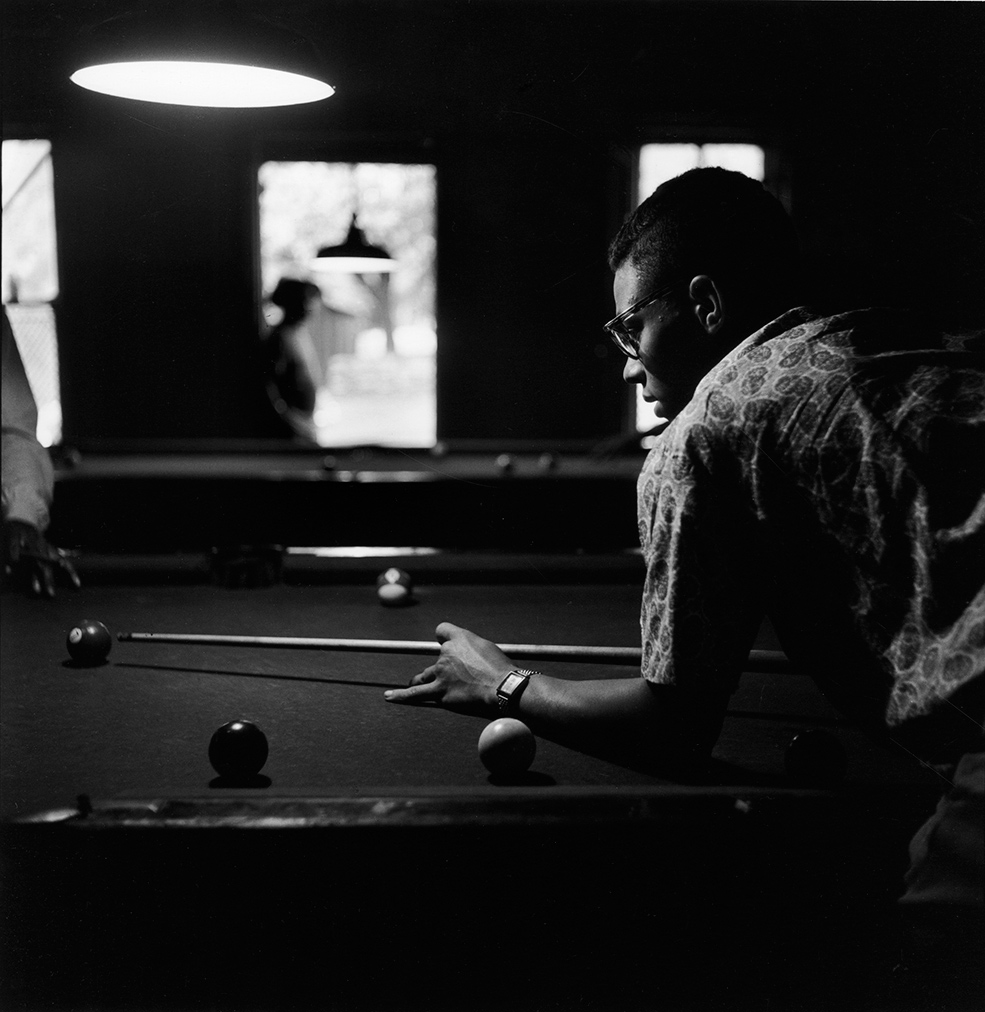

Untitled, Columbus, Ohio. Gordon Parks | (Courtesy and copyright The Gordon Parks Foundation, Courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.)

Tenement Dwellers, Chicago, Illinois. Gordon Parks | (Courtesy and copyright The Gordon Parks Foundation, Courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.)

After Fort Scott, Parks followed his peers north: St. Louis, Columbus, Detroit, Chicago. He tracked down old classmates, and interviewed and photographed them, making sure to highlight not only their struggles but also their successes. That was important, Haas explains, because by photographing his subjects in a family unit, or asking about their hopes and hobbies — one man was saving up for a Buick, another woman was photographed playing her piano — Parks defied the prejudices of the time.

"Many of LIFE's stories would have been couched in the terms of the middle-class American white family," Haas says. "So it would have been surprising, but also reassuring, to the white readership to see these family units — couples and children in front of their houses. I think Parks consciously set out to counter the stereotypes, to photograph those important markers which showed parents investing in their children's lives and future selves."

Untitled, St. Louis, Missouri. Gordon Parks | (Courtesy and copyright The Gordon Parks Foundation, Courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.)

Untitled, Chicago, Illinois. Gordon Parks | (Courtesy and copyright The Gordon Parks Foundation, Courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.)

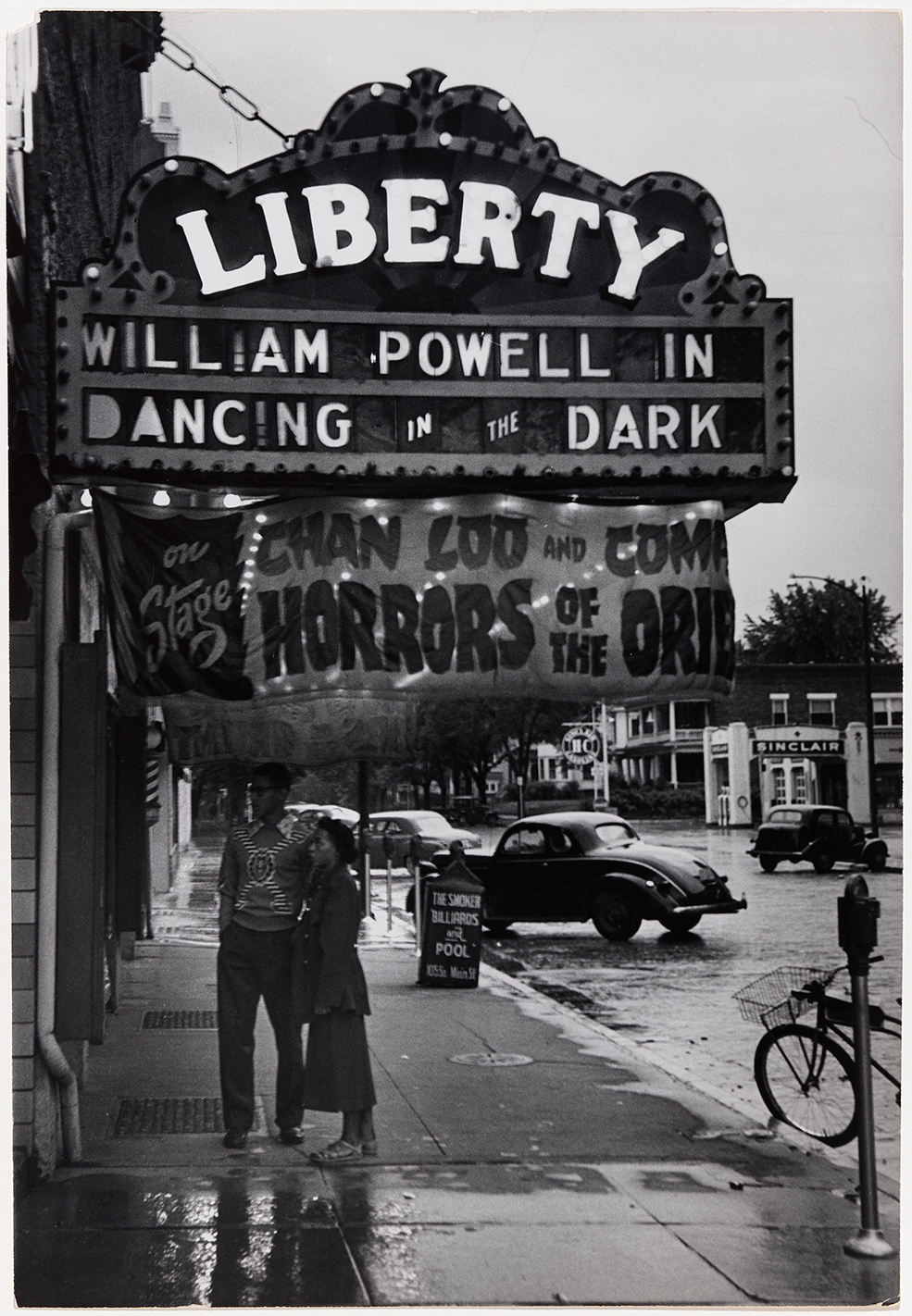

Untitled, Outside the Liberty Theater. Gordon Parks | (Courtesy and copyright The Gordon Parks Foundation, Courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.)

**Gordon Parks: Back to Fort Scott (Jan. 17 — Sept. 13, 2015), at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston**

Sarah Eberspacher is an associate editor at TheWeek.com. She has previously worked as a sports reporter at The Livingston County Daily Press & Argus and The Arizona Republic. She graduated from Northwestern University's Medill School of Journalism.

-

Ultimate pasta alla Norma

Ultimate pasta alla NormaThe Week Recommends White miso and eggplant enrich the flavour of this classic pasta dish

-

Death in Minneapolis: a shooting dividing the US

Death in Minneapolis: a shooting dividing the USIn the Spotlight Federal response to Renee Good’s shooting suggest priority is ‘vilifying Trump’s perceived enemies rather than informing the public’

-

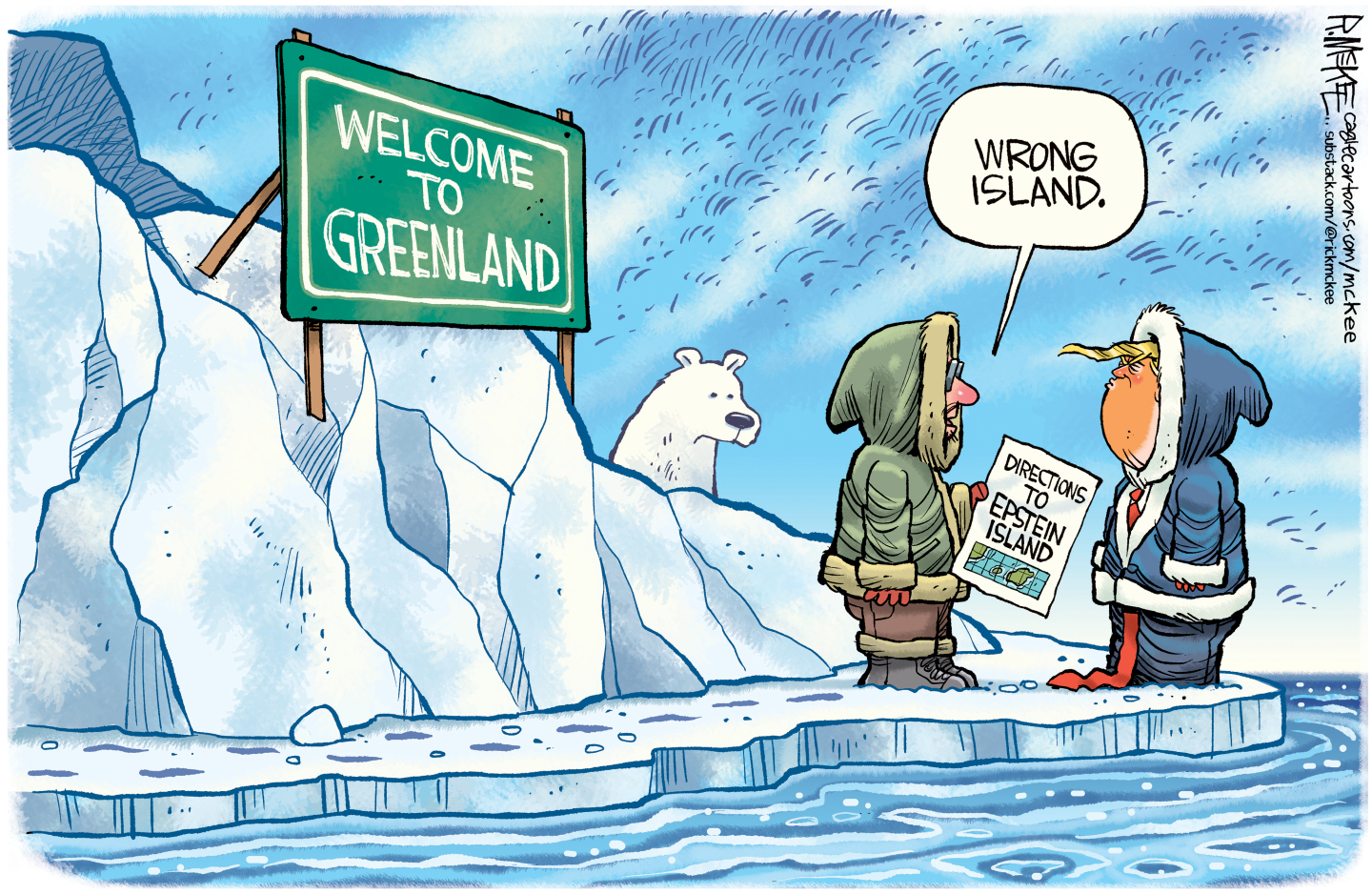

5 hilariously chilling cartoons about Trump’s plan to invade Greenland

5 hilariously chilling cartoons about Trump’s plan to invade GreenlandCartoons Artists take on misdirection, the need for Greenland, and more