Oculus Rift: all you need to know about virtual reality

How does a headset work, how much will they cost and what will the first one be like?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

This could be the year of virtual reality, at least in the minds of some critics. Several high-profile headset launches are scheduled for 2016, but how has the technology come back to the fore after time out in the cold, how does it work and what should we make of the soon-to-launch Oculus Rift – the first major headset to launch?

Why is virtual reality being hyped?

Virtual reality (VR) devices have failed miserably to catch on in the past due to limitations in computing and graphical power, which meant the products did not fully immerse their wearers in the fantasy world. The new headsets that will go on sale will take full advantage of gains in computing power and the backing of several high-profile companies to produce far more convincing experiences.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Oculus, the makers of the upcoming Rift headset was bought by Facebook for $2bn (£1.4bn) in 2014, after initial trials of the development kit highlighted an entertainment product with truly revolutionary capabilities. Despite the technological showcase, The Guardian says the company's biggest achievement has been "to get people excited about VR again".

Back in 2012, the company secured $2.4m (£1.7m) on crowdfunding website Kickstarter to fund their device. Arguably, those fans backing the return of VR got more than they bargained for. It has become a busy marketplace and several rival devices from household names are also on their way.

How does VR work?

Headsets display rich 3D environments with a full field of view to wearers, but they must also take in information and feedback from the user for a truly immersive experience.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

To do this, the display is matched to a series of components within the headset and peripherals.

Popular Science breaks down the technology into four bites: lenses, display, tracking and 3D audio. "Establishing a focal point is critical to perceiving depth," they say, and the lenses mounted inside the headset mean the "user's eyes are staring beyond the display and into the virtual environment".

A high-resolution display behind the lenses projects a stereoscopic image – two slightly warped images on each half of the screen, which the lenses combine into one sharp 3D image. When viewed in close proximity, "users are tricked into believing they're standing in a virtual world".

Then comes tracking. The unit is laden with sensors that track the user's movements. Peripherals including external sensors and a camera are linked to a PC to make sense of it all and react to the wearer's head and body positions to create a virtual world.

Audio is also a big factor. VR headsets such as the Rift use 3D audio to generate spatially accurate noises.

What can we do with VR?

Inevitably, gaming is one of the key applications of the headset. The upcoming PlayStation VR is one particular example of a device made purely with console gaming in mind, while HTC has partnered with US game developers and digital distributors Valve to develop the Vive headset.

As for the quality of the experience, ARS Technica describes playing space exploration and trading game Elite: Dangerous while wearing the Oculus Rift headset and coming across a binary sun system.

"It was, literally, breathtaking," they say. "I stared at it for probably a full minute, just marvelling in the stillness and enormity of space and the planets. In 3D, through the Rift, those suns had weight as they hung there in the black; the planet below has a looming solidity, and I felt a vertiginous sense of height as I looked down at it."

There are other uses beyond gaming. When Facebook chief Mark Zuckerberg bought Oculus in 2014, he envisaged using the devices to stream live events such as live sports. Using the example of tennis, he touted a future where fans could buy a virtual courtside ticket at Wimbledon.

Practical uses could see architects using them to show clients around renders of potential buildings or VR could help treat soldiers suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder.

These are ideas developers are now putting within touching distance of the consumer. Headsets will launch this year - but what of the first major release, the Oculus Rift?

Headset

The stereoscopic image in the Rift is displayed on two 2,160 x 1,200 OLED screens mounted within the headset, with low latency ensuring there is no blur or visible pixels in the image - a big step on from the development kit, which used a single display from a Samsung Note 3 pad.

The lenses are adjustable, meaning the wearer can fine-tune the Rift for the best experience possible, and the headset is coated in fabric for comfort – developers have focussed heavily on how the headset feels, especially the weight of the device.

Video and audio is sent to the Rift via a HDMI cable, with a DVI adapter available for linking it to laptops and older graphics cards. The HDMI cable is 10ft long and Wareable says it's "reasonably light so you don't feel like a dog chained to a lamppost" when using the headset.

Vertical and horizontal straps warp around the user's head and the final customer version has been designed with glasses-wearers in mind.

Controllers

The Rift will come with two choices in the controller department. The company has worked with Microsoft to make the Xbox One controller the default method of control and one will come with the device when deliveries begin.

However, worried that some users would be critical about controlling an immersive environment via conventional gaming methods, Oculus has developed the Oculus Touch controllers, which take the form of a conventional control pad but split into two separate modules. They loop around the user's hands, allowing for free movement of the arms, are motion sensitive and can sense individual hand gestures. Alphr describes them as "a powerful new input method", but they won't be launching with the Rift headset and may not be on the market until 2017

What does the Rift run on?

Despite it being bundled with an Xbox One controller, console support isn't quite confirmed. There's a number of 2D games currently out on the Xbox that can be played in a 3D setting (akin to sitting in a giant cinema), but soon we will learn the full extent of Xbox-Rift compatibility when VR games begin to hit the shelves.

To run the Rift on a PC, Oculus recommends a computer with an NVIDIA GTX 970 or AMD 290, Intel i5-4590, and 8GB RAM. This configuration will be held for the lifetime of the Rift and should drop in price over time.

Initially, the Rift was mooted to launch fully compatible with OSX and Linux, but the final consumer version of the product will only be Windows compatible.

Price and release

The Rift is due to launch on 28 March and pre-orders are already being taken for the headset. It could be on the shelves in shops in April.

The price is a sticking point though. In the US, the device will retail at $599, meaning a UK price around the £500 mark, which could turn out to be a major problem.

First, many critics have said it is difficult to describe the VR immersive experience and that potential customers really have to use it in order to get a sense of how it feels. Retailers may have to offer demos in order to convince people to part with their cash.

Second, the introductory price is higher than any current games console and again, it will be hard to convince consumers to purchase a peripheral that costs more than the device it is used with.

Finally, savvy consumers are unlikely to buy a VR headset from launch, opting instead to free-ride on others buying the devices and wait for a price cut. In time and with sufficient demand, newer, more powerful and cheaper headsets will launch.

If there's not enough early adopters of the headsets, game developers could be put off due to a lack of demand for VR ready titles.

-

Is Andrew’s arrest the end for the monarchy?

Is Andrew’s arrest the end for the monarchy?Today's Big Question The King has distanced the Royal Family from his disgraced brother but a ‘fit of revolutionary disgust’ could still wipe them out

-

Quiz of The Week: 14 – 20 February

Quiz of The Week: 14 – 20 FebruaryQuiz Have you been paying attention to The Week’s news?

-

The Week Unwrapped: Do the Freemasons have too much sway in the police force?

The Week Unwrapped: Do the Freemasons have too much sway in the police force?Podcast Plus, what does the growing popularity of prediction markets mean for the future? And why are UK film and TV workers struggling?

-

The pros and cons of virtual reality

The pros and cons of virtual realityPros and cons The digital world is expanding, for better and for worse

-

The Apple Vision Pro's dystopian debut

The Apple Vision Pro's dystopian debutIn the Spotlight Is "spatial computing" the next big thing?

-

Digital fashion and the metaverse

Digital fashion and the metaversefeature Virtual shopping malls are popping up all over the metaverse as demand for digital fashion grows

-

How cybercriminals are hacking into the heart of the US economy

How cybercriminals are hacking into the heart of the US economySpeed Read Ransomware attacks have become a global epidemic, with more than $18.6bn paid in ransoms in 2020

-

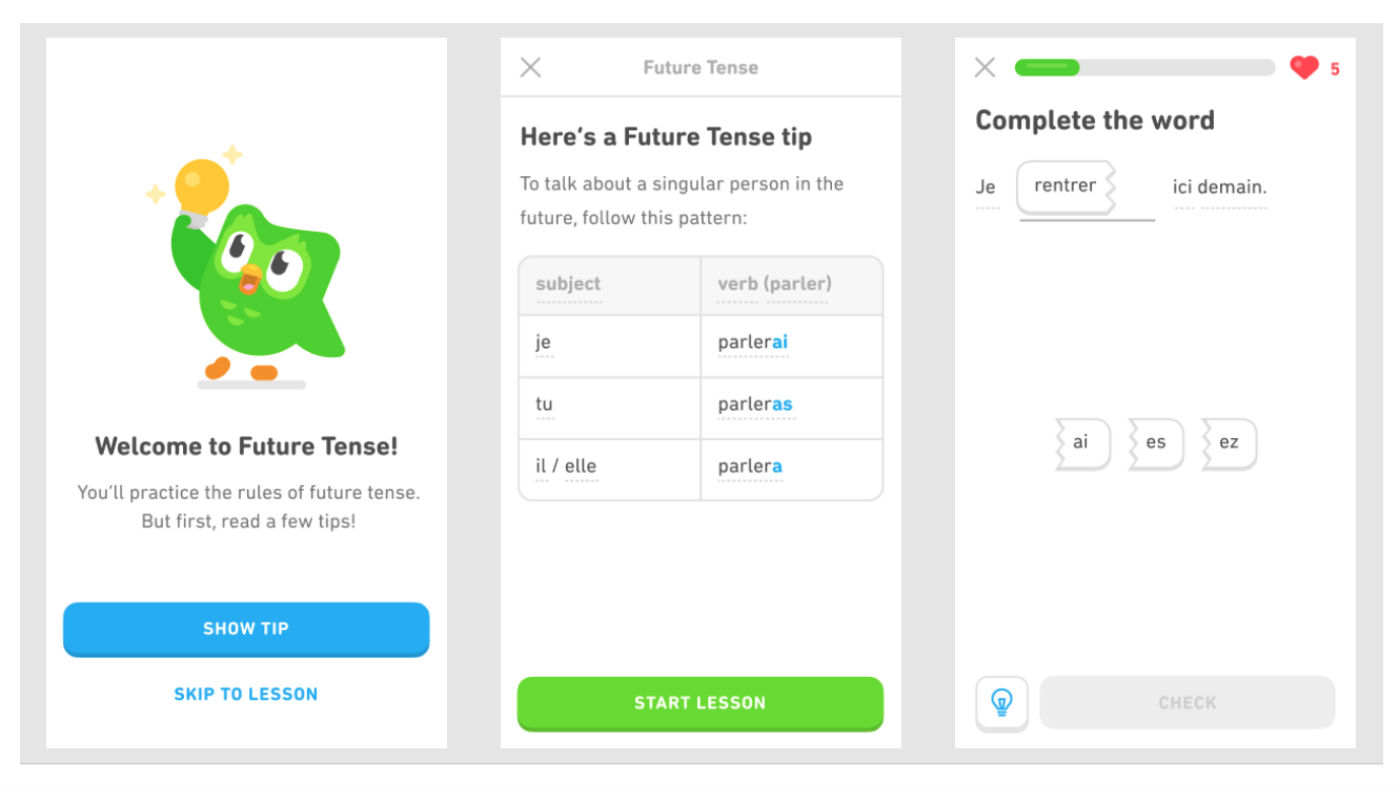

Language-learning apps speak the right lingo for UK subscribers

Language-learning apps speak the right lingo for UK subscribersSpeed Read Locked-down Brits turn to online lessons as a new hobby and way to upskill

-

Brexit-hobbled Britain ‘still tech powerhouse of Europe’

Brexit-hobbled Britain ‘still tech powerhouse of Europe’Speed Read New research shows that UK start-ups have won more funding than France and Germany combined over past year

-

Playing Cupid during Covid: Tinder reveals Britain’s top chat-up lines of the year

Playing Cupid during Covid: Tinder reveals Britain’s top chat-up lines of the yearSpeed Read Prince Harry, Meghan Markle and Dominic Cummings among most talked-about celebs on the dating app

-

Brits sending one less email a day would cut carbon emissions by 16,000 tonnes

Brits sending one less email a day would cut carbon emissions by 16,000 tonnesSpeed Read UK research suggests unnecessary online chatter increases climate change