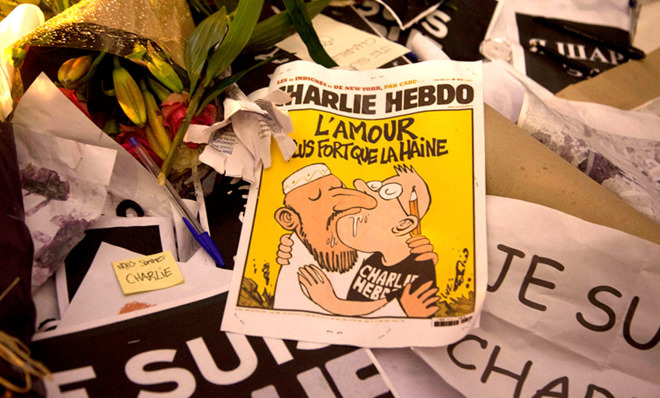

Slandering the prophet? Let the ink flow.

After the Charlie Hedbo attacks, we must reaffirm people's right to blasphemy

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The men who killed some of France's most beloved satirists yesterday left no doubt what their attack was all about: the Prophet Muhammad needed avenging. Methodically, carefully, and with relish, these men brought him the sacrifice they thought he required.

"We have avenged the Prophet Muhammad. We have killed Charlie Hebdo!" one attacker shouted, according to press reports quoting prosecutors.

There are five million Muslims in Paris. As Juan Cole points out, most are secular. Three men, out of two million who are not, committed an act of terror.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Should France apportion to Muslims some blame because a large number say they agree with the theory (at least) that people can be punished for desecrating the prophet? They should not. I don't think many Muslims actually believe this. I think those who do are conditioned to say they do, because an embrace of hierarchy and order helps them make sense of the world, and the uniqueness of certain pan-Islamic beliefs allows them to identify as part of a larger whole. But the fact that violence like this is so rare tells me that Western (or European) values are not losing.

When three people out of five million attack a newspaper, it suggests that their cause a losing one. Here's Juan Cole, again: "It was an attempt to provoke European society into pogroms against French Muslims, at which point al-Qaeda recruitment would suddenly exhibit some successes instead of faltering in the face of lively Beur youth culture (French Arabs playfully call themselves by this anagram). Ironically, there are reports that one of the two policemen they killed was a Muslim."

I worry about that. I worry that Europe will overreact.

I also worry that, as European society expresses its anger in the form of bigotry against Muslims, the political class will lose its nerve and fail to defend an almost absolutist concept of free speech and expression, which is the exact belief that the Charlie Hebdo attackers themselves found so noxious.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

In cosmopolitan America, we can barely get our heads around the idea that someone could be so offended by a cartoon that makes fun of a deity that they would sanction or commit terrorism simply to give their own rage an outlet. That is just thinking gone wrong; it seems so outside the orbit of cause and effect. But Judaism and Christianity also prohibit sacrilege and impose, in doctrine, penalties for those who desecrate the image of God. We just choose not to subscribe to those beliefs anymore. We discarded them because, while maybe we believe that God should always be honored, we believe more that holding on to that belief is harmful to us, as a plural people.

So some would have us ignore everything but the act itself. It was "unprovoked violence," says Ezra Klein. "Plenty of people follow all sorts of religions and somehow get through the day without racking up a body count. The answers to what happened today won't be found in Charlie Hebdo's pages. They can only be found in the murderers' sick mind."

To a point, Ezra. To a point. Murder and revenge is the logical extension of a doctrine that considers a craven image of a God to be blasphemy worthy of punishment. Free speech has consequences, one of which is that people feel freer to respond to political and symbolic speech with violence if they so choose. They will get arrested, or killed, for it, but in the mind's eye of someone who believes that your god has been raped in print, not responding in kind would be irrational.

Devious thinking of this type is what Charlie Hebdo ridiculed. The reason why they were so controversial is because a large number of people have chosen to believe something ridiculous and pre-modern. I said something about cosmopolitan America a while back, but the truth is that this country is not immune from this infection.

Bill Donahue of the Catholic League is one such believer. "Killing in response to insult, no matter how gross, must be unequivocally condemned. That is why what happened in Paris cannot be tolerated. But neither should we tolerate the kind of intolerance that provoked this violent reaction."

He uses the word provoke, because he assigns blame to the victims. He is right in a way that he would find to be so wrong. Offensive speech provokes. That's the point. But I think that's a good thing, not a bad thing. I think it's good that we choose to accept people's right to offend others. I think it's good that we speak out against beliefs that we find to be harmful. I think it's good that our acceptance and even embrace of intolerant speech sets an example.

It would be, in contrast, quite disappointing if we censored ourselves because we wanted to try and show respect for someone else's harmful, freely chosen point of view. If we withhold judgment from a bad belief, we sanction it. We nourish it. We ensure that, like Topsy, it will grow.

So, two ideas.

1. The attack ought to be connected to Islam, or religion, but not to Muslims. We cannot be afraid to criticize and even ridicule beliefs we find to be harmful and absurd. But neither is it humane nor in the interest of Europe, to indict the people who at worst have committed a thought crime and who at best can be persuaded to disregard that belief, just like practicing Christians and Jews (and even Bill Donohue, who doesn't incite violence) have in the U.S.

2. Free speech has consequences. Saying it doesn't is magical — it presupposes that there is some universal law which holds that good things will always happen when people are given license to speak their minds. Not always. But censoring political, symbolic, and religious speech, or trying not to offend anyone often have worse consequences. Censoring enfeebles our minds. Avoiding controversy removes the edge from humor. Protecting people from cartoons concedes sacred ground to much more harmful beliefs and practices.

Let the ink flow.

Marc Ambinder is TheWeek.com's editor-at-large. He is the author, with D.B. Grady, of The Command and Deep State: Inside the Government Secrecy Industry. Marc is also a contributing editor for The Atlantic and GQ. Formerly, he served as White House correspondent for National Journal, chief political consultant for CBS News, and politics editor at The Atlantic. Marc is a 2001 graduate of Harvard. He is married to Michael Park, a corporate strategy consultant, and lives in Los Angeles.

-

Democrats push for ICE accountability

Democrats push for ICE accountabilityFeature U.S. citizens shot and violently detained by immigration agents testify at Capitol Hill hearing

-

The price of sporting glory

The price of sporting gloryFeature The Milan-Cortina Winter Olympics kicked off this week. Will Italy regret playing host?

-

Fulton County: A dress rehearsal for election theft?

Fulton County: A dress rehearsal for election theft?Feature Director of National Intelligence Tulsi Gabbard is Trump's de facto ‘voter fraud’ czar