Hiding Afghan girls in plain sight

In Afghan families without sons, girls are dressed as boys to preserve the family's honor

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

"OUR BROTHER IS really a girl." One of the eager-looking twins nods to reaffirm her words. Then she turns to her sister. Yes, it is true.

They are two 10-year-old identical girls, each with black hair, squirrel eyes, and a few small freckles. Moments ago, we danced to my iPod as we waited for their mother to finish a phone conversation in the other room. Our sing-alongs sounded pretty good bouncing off the ice-cold cement walls of the apartment in the Soviet-built maze that is home to a chunk of Kabul's small middle class.

Now we sit on the gold-embroidered sofa, where the twins have set up a tea service consisting of glass mugs and a pump thermos on a silver-plated tray. Cassette tapes with Quran verses and peach-colored fabric flowers sit on a corner table where a crack has been soldered with Scotch tape. The twin sisters, their legs neatly folded underneath them on the sofa, are a little offended by my lack of reaction to their big reveal. Twin No. 2 leans forward: "It's true. He is our little sister."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

I smile at them and nod. "Yes." Sure.

A framed picture on a side table shows their brother posing in a V-neck sweater and tie, with his grinning, mustached father. It is the only photo on display in the living room. His oldest daughters speak a shaky but enthusiastic English, picked up from textbooks and satellite television from a dish on the balcony. We just have a language barrier here, perhaps.

"OK," I say, wanting to be friendly. "I understand. Your sister. Now, what is your favorite color, Benafsha?"

When it becomes each of the twins' turns to ask a question, they both want to know the same thing: Am I married?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

My response mystifies them, since — as they point out — I am very old. I am even a few years older than their mother, who at 33 is a married mother of four. The twins have another sister, too, in addition to their little brother. Their mother is also in the national parliament, I say to the twins. So there are many things I am not, compared to her. They seem to appreciate that framing.

Their brother suddenly appears in the doorway.

Mehran, age 6, has a tanned, round face, deep dimples, eyebrows that go up and down as he grimaces, and a wide gap between his front teeth. His hair is as black as that of his sisters, but short and spiky. In a tight red denim shirt and blue pants, chin forward, hands on hips, he swaggers confidently into the room, looking directly at me and pointing a toy gun in my face. Then he pulls the trigger and exclaims his greeting: phow.

Benafsha comes alive at my side, seeing the chance to finally prove her point. She waves her arms to call her brother's attention: "Tell her, Mehran. Tell her you are our sister."

I HAD BEEN researching a television piece on Afghan women, and Mehran and the twins' mother, Azita, has been a member of the country's fairly new parliament for four years. Elected to the Wolesi Jirga, one of the legislative branches installed a few years after the 2001 defeat of the Taliban, she had promised her rural voters in Badghis province that she would direct more of the foreign aid influx to their poor, far-flung corner of Afghanistan.

As some foreign diplomats and aid workers around Kabul came to know Azita as an educated female parliamentarian who not only spoke Dari, Pashto, Urdu, and Russian but also English, and who seemed relatively liberal, invitations to events poured in from the outside world. She was flown to several European countries and to Yale University in the United States, where she spoke of life under the Taliban.

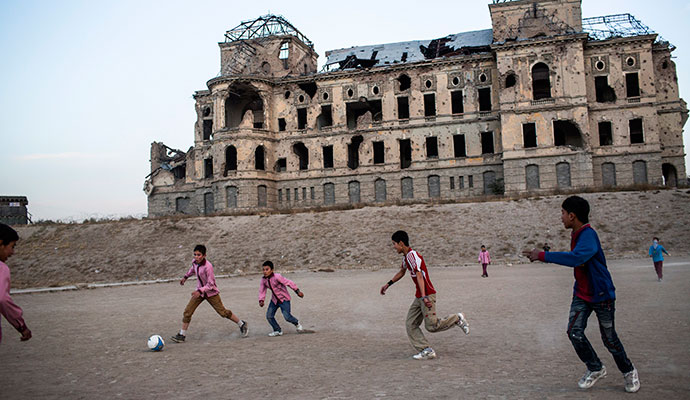

It was not unusual for Azita to invite foreigners to her rented home in Macroyan, either, to show her version of normal life in a Kabul neighborhood. Here, laundry flutters on the balconies of dirt-gray four-story buildings, interrupted by the occasional patch of greenery, and in the early mornings, women gather at the hole-in-the-wall bakeries while men perform stiff gymnastic exercises on the football field.

Azita is one of few women with a voice, but to many, she remains a provocation, since her life is different from that of most women in Afghanistan and a threat to those who subjugate them. In her words: "If you go to the remote areas of Afghanistan, you will see nothing has changed in women's lives. They are still like servants. Like animals. We have a long time before the woman is considered a human in this society."

SHE LOOKS AT me for a moment, where we sit in her bedroom. "I never want my daughters to suffer in the ways I have suffered. I had to kill many of my dreams. I have four daughters. I am very happy for that."

Four daughters. Only four daughters? What is going on in this family? I hold my breath for a moment, hoping Azita will take the lead and help me understand. And she does.

"Would you like to see our family album?"

We move back into the living room, where she pulls out two albums from under a rickety little desk. The children look at these photos often. They tell the story of how Azita's family came to be.

First: a series of shots from Azita's engagement party in the summer of 1997. Azita's first cousin, whom she is to marry, is young and lanky. She is the elite-educated daughter of a Kabul University professor. Her husband-to-be: the illiterate son of a farmer. In one shot, her matte, powdery face is streaked with vertical lines running from dark brown eyes.

A few album pages later, the twins pose with Azita's mother, a woman with high cheekbones and a strong nose in a deeply lined face. Soon, a third little girl makes her appearance in the photos. Middle sister Mehrangis has pigtails and a round face.

Azita flips the page: Nowruz, the Persian New Year, in 2005. Four little girls in cream-colored dresses. All ordered by size. The shortest has a bow in her hair. It is Mehran. Azita puts her finger on the picture. Without looking up, she says: "You know my youngest is also a girl, yes? We dress her like a boy.

"They gossip about my family. When you have no sons, it is a big missing, and everyone feels sad for you." Azita says this as if it is a simple explanation.

Having at least one son is mandatory for good standing and reputation here. A family is not only incomplete without one; in a country lacking rule of law, it is also seen as weak and vulnerable. So it is incumbent upon every married woman to quickly bear a son — it is her absolute purpose in life, and if she does not fulfill it, there is clearly something wrong with her in the eyes of others. She could be dismissed as a dokhtar zai, or "she who only brings daughters." Still, this is not as grave an insult as what an entirely childless woman could be called — a sanda or khoshk, meaning "dry" in Dari. But a woman who cannot birth a son in a patrilineal culture is — in the eyes of society and often herself — fundamentally flawed.

The literacy rate is no more than 10 percent in most areas, and many unfounded truths swirl around without being challenged. Among them is the commonly held belief that a woman can choose the sex of her unborn baby simply by making up her mind about it. As a consequence, a woman's inability to bear sons does not elicit much sympathy. Instead, she is condemned both by society and her own husband as someone who has just not desired a son strongly enough.

FOR AZITA, THE lack of a son stood to impede all she was trying to accomplish as a politician. When she arrived with her family in Kabul in 2005, sneers and suspicion about her lack of a son soon inevitably extended to her abilities as a lawmaker and a public figure. Her visitors would offer their condolences when they learned about her four daughters. She found herself being cast as an incomplete woman. Fellow parliamentarians, constituents, and her own extended family were unsympathetic: How could she be trusted to accomplish anything at all in politics when she could not even give her husband a son? Without a boy to show off to the constant stream of visiting political power brokers, her husband also grew increasingly embarrassed.

Azita and her husband approached their youngest daughter with a proposition: "Do you want to look like a boy and dress like a boy, and do more fun things like boys do, like bicycling, soccer, and cricket? And would you like to be like your father?"

She absolutely did. It was a splendid offer.

All it took was a haircut, a pair of pants from the bazaar, and a denim shirt with "superstar" printed on the back. In a single afternoon, the family went from having four daughters to being blessed with three little girls and a spiky-haired boy. Their youngest would no longer answer to Mahnoush, meaning "moonlight," but to the boy's name Mehran. To the outside world — and especially to Azita's constituents back in Badghis — the family was finally complete.

Some, of course, knew the truth. But they, too, congratulated Azita. Having a made-up son was better than none, and people complimented her on her ingenuity. When Azita traveled back to her province — a more conservative place than Kabul — she took Mehran with her. In the company of her 6-year-old son, she found she was met with more approval.

The switch also satisfied Azita's husband. Tongues would now cease to wag about this unlucky man burdened with four daughters, who would need to find husbands for all of them and have his line end with him. In Pashto, Afghanistan's second official language, there is even a deprecating name for a man who has no sons: He is a meraat, referring to the system where an inheritance, such as land assets, is almost exclusively passed on through a male lineage. But since the family's youngest took on the role of a son, the child has become a source of pride to her father. Mehran's revised status has also afforded her siblings considerably more freedom, as they can leave the house, go to the playground, and even wander to the next block, if Mehran is along as an escort.

There was one additional reason for the transition. Azita says it with a burst of low laughter, leaning in a little closer to disclose her small act of rebellion: "I wanted to show my youngest what life is like on the other side."

That life can include flying a kite, running as fast as you can, laughing hysterically, jumping up and down because it feels good, climbing trees to feel the thrill of hanging on. It is to speak to another boy, to sit with your father and his friends, to ride in the front seat of a car and watch people out on the street. To look them in the eye. To speak up without fear and to be listened to, and rarely have anyone question why you are out on your own in comfortable clothes that allow for any kind of movement. All unthinkable for an Afghan girl.

But what will happen when puberty hits?

"You mean when he grows up?" Azita says, her hands tracing the shape of a woman in the air. "It's not a problem. We change her into a girl again."

Adapted from The Underground Girls of Kabul: In Search of a Hidden Resistance in Afghanistan. Copyright © 2014 by Jenny Nordberg. Published by Crown Publishers, an imprint of Random House LLC.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day