The hustlers, builders, prostitutes, entrepreneurs, bad boys, and dreamers of Ghana's biggest slum

Welcome to Sodom and Gomorrah

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

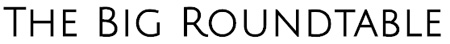

Sodom and Gomorrah is the biggest slum in Ghana, a country that sprouts shantytowns like weeds. There are about eighty thousand Sodomites crammed onto less than half a square mile in the capital city, Accra, near a toxic lagoon and a channel of raw sewage. They are surrounded by the guts of one of the fastest-growing economies in West Africa, miles of teeming factories, markets, and workshops. To get to Sodom and Gomorrah, you must cross a river of shit. To do that, you need Fusheini's bridge.

It's Sunday, the day of rest in Sodom and Gomorrah. Fusheini Abdullah sits on a bench at the mouth of his bridge, clutching the length of blue rope that he pulls taut to enforce the ten pesewa (three cent) toll. Traffic is low, mostly people in immaculate church clothes and kids coming home from madrassa. The canal below looks like freshly tilled soil until a spotless white heron lands on the water, making the blanket of excrement and trash ripple. The smell is gut-wrenching in the mid-day heat, made more intense by the pall of acrid white smoke from the flaming dump where the canal meets the lagoon.

The canal sits between Sodom and Gomorrah and central Accra. North of the slum is Agbogbloshie, home to a scorched field where tons of the world's discarded electronics are burned for scrap. South are the glass towers and modernist hulks of Ghana's government. The waterway was once a clear blue river running through the city until some bright soul decided it would be better off as a sewer and buried everything but the last, filth-choked mile, renaming it the Agbogbloshie Canal. It's a study in the kind of planning that has the city teeming with cholera, typhoid, and malaria.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The bridge, in comparison, is a masterpiece of careful design. It's an achievement, considering Fusheini is no engineer. He has been working since the age of six, when his polygamous father died, leaving everybody with nothing. He had to quit school almost as soon as he started, which to this day makes him angry. Fusheini spent his entire childhood on the family farm, doing backbreaking work growing yams and corn, until the family outgrew the farm. Then he discovered that there was no work to be had in Ghana's stunted Northern Region, especially not for grown men who can barely speak Twi — the nation's lingua franca — let alone English, which is Ghana's official language.

(More from The Big Roundtable: My Rehab: Coming of age in purgatory)

So Fusheini moved to Accra and did every job he could find. He worked construction, then as a butcher, and then for years as a low-level scrap dealer, pushing a bulky wooden cart miles around the city by hand, before he started to get too old for it. Then he saw the river of shit, and bet everything on a bridge.

It cost a small fortune: 16,500 cedis, almost $6,000 U.S., in iron beams, timber, and payoffs. He is particularly proud of the iron — very pricey. The first few versions of his bridge were timber and washed away every time it rained too hard. The metal bridge, in comparison, is solid. Fusheini leans forward to draw a blueprint in the dirt path in front of the bridge: two long beams, laid on concrete posts sunk into the banks of the canal, with another crossbeam every meter or so, like a ladder.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Laying the bridge was a feat of improvised engineering. The budget didn't allow for cranes, tools, or actual engineers, so it was just Fusheini, a couple of guys from the neighborhood, a car, and some rope. They tied the rope to each of the long beams, waded through the muck of the canal to the other side and hitched it to a car, which drove forward, pulling the iron into place. Every day since, Fusheini has collected 50 cedis (about $20) a day in tolls, which would mean the bridge paid for itself in less than a year. Fusheini, however, wants it on the record that the bridge is an act of charity. Many people who use it, school kids especially, don't have to pay.

(Yepoka Yeebo/The Big Roundtable)

In the beginning there was chaos, a few thousand people squatting on a mangrove swamp. The entire area of what is now called Sodom and Gomorrah used to be covered by shrubs and trees tough enough to survive the saltwater tides of the Korle Lagoon, but all that's left now is a flood-prone flat of mud and sand, owned by the government of Ghana. Order came in the form of profiteers like Fusheini, men and women of questionable authority who parceled out land they didn't own, broke into the mains at the hospital across the highway to pipe water in, and plied some big man at the Electricity Company of Ghana with livestock until he put up a transformer. A doctor who used to keep his horses on the swamp told the first squatters that anything they built would be swept away like the biblical Sodom and Gomorrah. The name stuck.

(More from The Big Roundtable: The troubled life and complicated death of Jana Van Voorhis)

In the twenty years since the first squatters arrived, Sodom and Gomorrah, officially named Old Fadama, has evolved into home for some of the most eager, energetic, and determined migrants in Ghana. Crowded into this miserable corner of the capital city, without much law to guide them, these people have built a community that has helped lift them out of poverty.

But because everything they do is haphazard, unplanned, and illegal, Sodom and Gomorrah has quickly become a problem for the rest of Accra. It causes floods, harbors armed robbers, and thwarts hundred-million-dollar infrastructure projects. So even as it has grown, Sodom and Gomorrah has been constantly threatened with destruction.

(More from The Big Roundtable: The man who would save jazz)

Aliwu Achanso is spending his day off work by the bridge, watching a group of men talk smack over a game of Ludo (similar to Parcheesi). Achanso is middle class by Ghanaian standards. He can earn as much as 1,500 cedis a month — about $500 — as a metal worker on construction sites. He builds iron frames for reinforced concrete buildings, which is a lucrative job in a construction boom, almost worth the three years of penury it took to learn the trade.

Despite earning a good salary, Aliwu lives in the slum because it means he can send a serious amount of money home to his parents and still have enough to feed himself and keep a roof over his head. "Everything is cheap here, not too costly as it is in town," he says. "People may think the people in the slum are foolish people," he says. "But they know why they're here."

Still, he is trying to save enough money to leave. He's getting sick of being branded a criminal just because he lives in Sodom and Gomorrah: "They combine all of us as bad people." Plus he just doesn't feel safe any more. "I've been seeing so many disasters here."

Two years ago, his room — a wooden shack — burned down, wiping out almost everything he owned. It was the worst setback he'd faced since he first arrived in Accra. It took him about two months of work to rebuild his home, this time in fire-proof concrete. Achanso isn't worried about spending money building a home he doesn't actually own. He just won't leave without alternative accommodation or compensation. He did, after all, pay about $180 for the original shack and the land under it, so he's entitled to something, he says. "They cannot just sack us like slaves or animals."

READ THE REST OF THIS STORY AT THE BIG ROUNDTABLE.

This story originally appeared at The Big Roundtable. Writers at The Big Roundtable depend on your generosity. All donations, minus a 10 percent commission to The Big Roundtable and PayPal's nominal fee, go to the author. Please donate.

-

What to know before filing your own taxes for the first time

What to know before filing your own taxes for the first timethe explainer Tackle this financial milestone with confidence

-

The biggest box office flops of the 21st century

The biggest box office flops of the 21st centuryin depth Unnecessary remakes and turgid, expensive CGI-fests highlight this list of these most notorious box-office losers

-

What are the best investments for beginners?

What are the best investments for beginners?The Explainer Stocks and ETFs and bonds, oh my