Interstellar is a frustrating, over-reaching mess. You should see it anyway.

Christopher Nolan's latest shows the kind of ambition rarely seen in blockbusters

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Interstellar didn't even hit general release until today, but the critical reaction is already as polarized as any mainstream movie released this year. FirstShowing.net claims Interstellar is a film with the power to remind humankind "that we can dream, that we get to breathe this fresh air on this beautiful planet, that we get to smile, cry, and laugh." The New York Post calls it "one of the most exhilarating film experiences so far this century."

That's a lot of baggage to saddle a movie with, but the responses on the other extreme are no less unequivocal. The Boston Herald says Interstellar is "a more pretentious, less plausible Armageddon." In a D+ review, The Fresno Bee complains that star Matthew McConaughey is "the only thing that keeps the movie from completely collapsing on itself."

I don't agree with any of those reactions, but I understand where they come from. Interstellar is a beautiful, irritating, awe-inspiring mess. It's the kind of movie Hollywood simply doesn't make any more — and that's exactly why you should see it.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

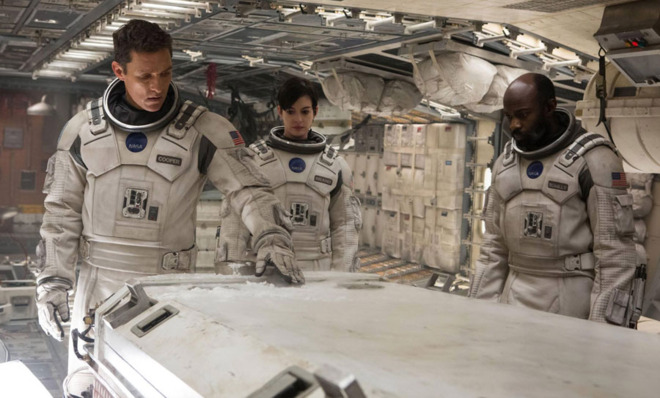

Interstellar is set at an unspecified point in the future in which Earth is on the verge of environmental collapse that will inevitably lead to the destruction of humankind. The days are interrupted by regular, debilitating dust storms, and even brilliant engineers like Cooper (McConaughey) have turned to farming in a meager attempt at survival. Cooper is a widower with two adolescent children, including a precocious and adoring daughter (Mackenzie Foy) — but when he's approached with the opportunity to launch into space as part of a mission to find a new, sustainable planet for humankind to populate, he leaves them behind in an attempt to secure their long-term survival.

Interstellar began life as a Steven Spielberg project, but it owes its existence to the track record of Christopher Nolan. After breaking out with Memento, Nolan pioneered the modern superhero blockbuster with the Dark Knight trilogy and turned an untested concept like Inception into a buzzy, $825 million worldwide hit.

But despite all those successes, it's impressive that Nolan got to make Interstellar his way, because this isn't how the movie industry works in 2014. Directors don't get to spend $165 million on a single-minded passion project with no proven commercial prospects. They don't get to hide almost every detail of the movie, right up to its release date, including much of the story and several of the stars. They don't get to shoot on film, and they certainly don't get to submit a final cut that sprawls for almost three hours. (The Guardian has an excellent breakdown of how Interstellar came together, and why this kind of movie has become so rare.)

Interstellar is something different. It's Nolan's most personal film, and also his lumpiest, and probably his worst. (You can imagine the younger Christopher Nolan, who didn't waste a frame in Memento, rolling his eyes at the many digressive indulgences of Interstellar.) But in a landscape of prepackaged and pre-sold Hollywood blockbusters, it's also uncommonly daring, and that's not something to take lightly.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

2014 has seen no shortage of blockbusters. Everybody liked Captain America: The Winter Soldier and Guardians of the Galaxy; nobody liked Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles and Transformers: Age of Extinction. But while the quality of those movies varied, the scope and structure didn't. With the possible exception of Noah — a similarly long, similarly star-studded passion project for director Darren Aronofsky — 2014's blockbusters have been predictable, from their execution to critical and commercial reception.

Steven Spielberg spent a lot of time on Interstellar before giving up the director's chair, and it's easy to see his fingerprints on the project; the movie aims for the kind of sci-fi sentimentality he pioneered in Close Encounters of the Third Kind and E.T. But Christopher Nolan, rewriting a script by his brother Jonathan, recast the movie in his own image.

Christopher Nolan's work has been described, inaccurately, as chilly or dark — but at heart, he's always been a sentimentalist. Just look at the platitudes that make up the moral backbone of his Dark Knight trilogy: "Why do we fall? So we can learn to pick ourselves back up again." "It's not who I am underneath, but what I do that defines me." "A hero can be anyone." "Make the climb." Even The Dark Knight — which is, in theory, the most downbeat entry of the franchise — concludes the Joker's arc by disproving his grim outlook on the human race.

Those sentiments tend to get lost in the other trappings of your average Christopher Nolan movie: speechifying villains, bombastic Hans Zimmer scores, mind-bending special effects. But they're impossible to miss in Interstellar, which slows down at a pivotal point in the narrative so Anne Hathaway can deliver a speech about love. Despite the film's sci-fi trappings, it gradually becomes clear that love is where Nolan's actual interest lies — a force which, in the film's own words, is both observable and powerful. By the end of Interstellar, Nolan has all but abandoned the pseudo-science of black holes and alien planets in favor of the raw emotion of human connection.

Based on the reactions I've seen, this is where Interstellar lost many critics; where I suspect it will lose much of its audience; and, full disclosure, where it kind of lost me. The emotions that the film wants to conjure are anything but subtle — Dylan Thomas' "Do not go gentle into that good night" is read aloud no less than three times — and for everything I admired about Interstellar, I never quite made the big, big buy the film eventually asks viewers to make.

But Interstellar isn't a movie in which "Is it good?" is the most important or interesting question. There's a warm place in my heart for passion projects, and it's refreshing to watch a Hollywood director aim for the fences, even when several of his biggest swings fail to connect. Hollywood has released better movies in 2014, and worse movies that hold together much better — but few as risky or ambitious. We need more movies like Interstellar, and that's more than enough reason to see it.

Scott Meslow is the entertainment editor for TheWeek.com. He has written about film and television at publications including The Atlantic, POLITICO Magazine, and Vulture.

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Earth is rapidly approaching a ‘hothouse’ trajectory of warming

Earth is rapidly approaching a ‘hothouse’ trajectory of warmingThe explainer It may become impossible to fix