Why you probably don't have Ebola — even if you shook hands with America's 'patient zero'

The virus is terrifying, but probability and a dream team of rapid responders are on your side

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

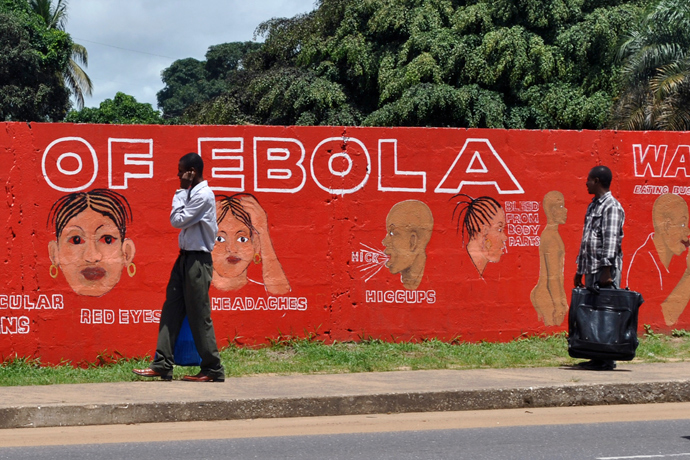

After a hectic trip from Liberia's capital of Monrovia to the airport, you finally make it onto your U.S.-bound plane and take your seat. The man next to you appears healthy and friendly. You introduce yourself, shake hands, and have an uneventful journey of small talk as you head back to Dallas, Texas. A few days later, you receive an urgent call from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: The man who sat next to you on the plane just tested positive for the Ebola virus.

You start to feel panic rise in your chest, reliving the fateful handshake over and over. Your anxiety is perfectly understandable — but unnecessary. Even if you've directly touched "patient zero," your chance of catching Ebola through a single contact of unbroken skin is pretty low.

As most Americans now know, this is no longer the realm of pure speculation. On Tuesday, the CDC announced the arrival of Ebola in the U.S., after a Texas hospital patient who recently traveled to Liberia was diagnosed with the virus.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

But if your first instinct is to panic, don't. Yes, Ebola sounds terrifying; it is so ensconced in our public consciousness that it has become conversational shorthand for a horrifying ilness. But Ebola is not the disease of our imaginations.

Ebola is a virus, which is a bundle of RNA that contains code to make proteins. Although it is relatively inert on its own, once it infects a human body — through cuts in your skin or through mucous membranes like the inside of your mouth — it sneaks into your cells. Using the body’s own machinery, it tricks cells into making thousands of new viruses and then releasing them into the bloodstream. Seven to 10 days after this process starts, an infected person starts to feel pretty terrible, suffering from muscle pains, fever, and other flu-like symptoms. And Ebola’s symptoms only get worse from there: Patients develop diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain. The virus infects your liver, leading to liver failure. The body’s blood coagulation process is disrupted and uncontrollable bleeding may start. Patients become confused, their kidneys shut down, and, about 50 percent of the time, they die.

It all sounds pretty horrible, and it is. But what's really scary about Ebola is that such a high percentage of those who acquire the infection end up dying — a statistic called case fatality rate. This ranges from 50-70 percent in a given Ebola epidemic, among the highest case fatality rates of any infection in the world. Death rates have barely budged since the introduction of modern medicine in outbreak zones.

However, despite Ebola's high case fatality rate, its arrival should not be particularly alarming for the general population in countries with well-developed public health systems. There are several reasons for this.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

First, unlike many other viral illnesses, people with Ebola who have not yet developed signs of the disease are not yet contagious, meaning we can identify those at risk of infecting others and prevent them from entering public areas. Screening processes based on identifying people with fever have already been successfully implemented in airports around affected areas in West Africa.

Second, while Ebola is very contagious with close contact, Ebola does not spread through air, water, or food. Unlike infections such as influenza or measles — which you can acquire just from being in the same room as an infected person — Ebola transmission requires direct contact with a patient’s blood, bodily fluids, broken skin, or mucous membranes.

So even if you were on that September 19th flight from Liberia to Dallas and shook the hand of America's "patient zero," your risk of transmission remains relatively small. Studies have found that the disease is spread in places like Liberia and Sierra Leone through family members caring for sick individuals, ritual washing of victims at funerals, or helping prepare a corpse for burial. In fact, one of the strongest factors fueling the current epidemic has been a lack of public health infrastructure in the countries affected. Even if more Ebola patients are diagnosed in the U.S., don't expect the devastation here that we’ve seen elsewhere.

We have public health policies, procedures, infrastructure, and personnel in place for precisely these situations. For decades, men and women have sat around large tables in government buildings, drinking terrible coffee, talking about the precise details of what to do in the event of exactly this type of biological emergency. Officials have created carefully coordinated plans that detail every aspect of what will take place during an outbreak, from command structures and the placement of public health equipment to where people will enter and leave buildings. Additionally, we have in place small armies of public health workers whose job it is to investigate and test every single person who may have been in contact with a patient afflicted with a deadly virus. This response is rapid, coordinated, and effective. Because of it, we can expect any Ebola outbreak in the U.S. to be smaller and more contained than those seen in Liberia. This approach can and does work, as evidenced by Nigeria’s success containing its Ebola outbreak.

Although Ebola is a terrifying disease that we must take seriously, you probably don't see the work public health officials are doing every day to prevent an outbreak. In public health, we have a saying that the better we do, the less people notice.

Dr. Stern-Nezer is a neurology resident at Stanford Hospital with a degree in public health from UC Berkeley. She has also served as a bioterrorism preparedness coordinator, working on public health response. Dr. Monroe-Wise is an internal medicine physician doing her subspecialty training in infectious diseases at the University of Washington. She obtained a degree in epidemiology from Johns Hopkins University and spent years living in Sub-Saharan Africa.