Can the U.S. Army degrade and destroy Ebola?

Obama is sending 3,000 troops to West Africa to stop the deadly outbreak. But 250,000 people could already be infected by Christmas.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

As the Ebola epidemic in West Africa accelerates beyond the capacity to count its toll, an unprecedented escalation in global support is evident, led by U.S. President Barack Obama's call for U.S. military intervention. In what will amount to the largest humanitarian commitment since the American response to the 2004 earthquake and tsunami in Aceh, Indonesia, the White House announced late on Sept. 15 that an estimated 3,000 military personnel will deploy to the Ebola-ravaged West African nations, alongside a significant increase in civilian mobilization.

Obama committed the United States, in what the White House has dubbed Operation United Assistance, to spend some $750 million and deploy up to 3,000 U.S. military personnel, primarily targeting Ebola control in Liberia. The president formally announced the operation on Sept. 16 in a speech at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in Atlanta.

During his speech last week he reassured Americans that "the chances of an Ebola outbreak here in the United States are extremely low." However, when it came to the potential devastation Ebola posed to West Africa, he was adamant about its urgency:

Article continues belowThe Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

"In West Africa, Ebola is now an epidemic of the likes that we have not seen before. It's spiraling out of control. It is getting worse.... And if the outbreak is not stopped now, we could be looking at hundreds of thousands of people infected, with profound political and economic and security implications for all of us. So this is an epidemic that is not just a threat to regional security — it's a potential threat to global security...."

(More from Foreign Policy: Water wars)

This dramatic increase in U.S. commitment comes alongside beefed-up responses from several countries, largely focused on Sierra Leone. The Cuban government is sending 165 health professionals to that country; China is deploying 59 health workers; the U.K. government has promised to construct a 62-bed hospital in the country's capital, Freetown; and many other nations have promised other modest forms of assistance. The French government, on a significantly more modest level, has committed 20 experts in biological disasters to its former colony Guinea.

The scale of the U.S. response to Ebola, primarily focused on Liberia's staggering outbreak, dwarfs that of all other nations and to date is the only external support that will involve uniformed military engagement. Overall, the world's newfound sense of immediacy in the Ebola fight is coming late, and the response will succeed — or fail — based on the pace of execution in getting these much-needed resources on the ground.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

At this moment, Ebola is spreading out of control in three countries — Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone — and spillover has resulted in infection in West Africa's powerhouses: Senegal (one case to date) and Nigeria (two distinct clusters of connected cases). Weeks ago, the Council on Foreign Relations' John Campbell, former ambassador to Nigeria, and I warned in an on-the-record council briefing that the spread of Ebola inside Nigeria, particularly in Lagos — a city with a population of approximately 22 million — would put the world's epidemic into completely uncharted territory.

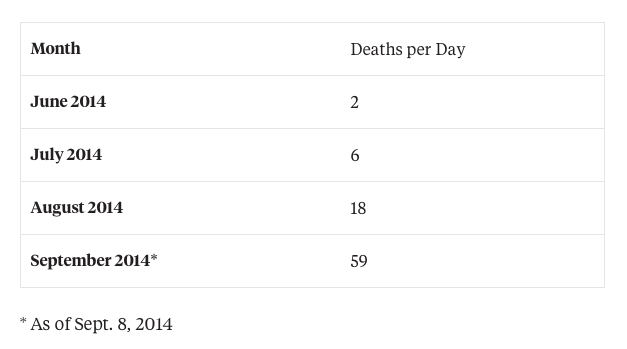

Today all epidemic-responding parties characterize the epidemic as "out of control," and in Liberia as "rising exponentially." During the first eight days of September, Liberia alone had 500 new cases, which is more than the total number of cases in most previous Ebola outbreaks. Conservatively, the laboratory-confirmed case count is threefold below the actual number of people infected, which could put an estimate of today's caseload as high as 15,000 cumulative, perhaps 12,000 actively infected. According to the WHO, in Liberia, "The demands of the outbreak have completely outstripped the government's and partners' capacity to respond. Fourteen of Liberia's 15 counties have now reported confirmed cases. Some 152 health care workers have been infected and 79 have died. When the outbreak began, Liberia had only one doctor to treat nearly 100,000 people in a total population of 4.4 million people. Every infection or death of a doctor or nurse depletes response capacity significantly."

The pace of Liberia's epidemic is accelerating:

To put this in historical perspective, the Mongolian bubonic plague of 1348 to 1351 struck with ferocity across the Middle East and Europe, claiming about a third of the European population. In his masterpiece Plagues and Peoples, William McNeill estimates that European diseases — including measles, influenza, tuberculosis, and pertussis — obliterated Amerindian populations after 1492, killing up to 90 percent of some tribes. But after the first age of globalization ended, the era of killer plagues also waned — until the 1918 Spanish influenza pandemic. Depending on whose database one draws from, that flu globalized in three waves over 18 months, claiming between 50 million and 75 million lives. It spread rapidly, proved highly contagious, and killed about 2 percent of the infected. Its spread was aided by the world's first globalized war, World War I.

The next great plague emerged in the late 1970s out of the American blood products market and gay communities, killing nearly 100 percent of those infected: HIV or AIDS. Its global spread was ensured by the combined impact of jet-set gay liberation and the U.S. export of contaminated blood products. Though HIV is not airborne, and causes a slow disease process that kills after a decade of infection, some 35 million people are now living with that virus in their bodies, according to UNAIDS.

Although I have written two books that draw heavily on Ebola epidemic experiences, and earned a Pulitzer Prize for my coverage of the 1995 Kikwit epidemic, I never imagined the global spread of the hemorrhagic virus and would not have conceived of placing it on a list of plagues.

(More from Foreign Policy: All the Ayatollah's men)

This hesitancy is because:

- the virus infects blood, and can only be passed on via direct contact with blood and bodily fluids (infecting the blood vessel cells);

- people infected with Ebola are quickly made too ill to travel, board an airplane on their own, or engage in physical activities; and

- outbreaks are largely nosocomial, meaning the virus is spread within health facilities and can be stopped with proper infection-control procedures.

But the 2014 Ebola epidemic has forced me — and the U.S. national security establishment — to rethink the virus's potential. There have been at least two cases of infected individuals traveling to another country, spreading the virus to Nigeria and Senegal. Within Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Guinea, transmission of Ebola has gone far beyond the nosocomial setting. Indeed, there is little evidence of spread inside health facilities except to the doctors and nurses themselves.

The virus is out of all forms of control, spreading in homes, businesses, schools, funerals, markets — wherever, it seems, people congregate.

Michael Osterholm of the University of Minnesota recently suggested in The New York Times that Ebola might mutate to become an airborne contagion. And he warned: "This is about humanitarianism and self-interest. If we wait for vaccines and new drugs to arrive to end the Ebola epidemic, instead of taking major action now, we risk the disease's reaching from West Africa to our own backyards." Osterholm's concern about airborne Ebola mirrors Obama's comments during his Sept. 7 appearance on Meet the Press, when he warned that a mutated Ebola could threaten the American homeland.

I do not believe that the reason to stop Ebola is self-protection. It seems clear to me that the people of Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Guinea are in the grips of their plague, claiming 14th-century levels of carnage. No matter how vigorously the countries' neighbors try to erect walls around the stricken nations, hoping to keep catastrophe from claiming their populations, this virus will spread. Yes, it is mutating — a recent paper in Science shows that more than 300 mutations have already occurred. But I do not share Osterholm's fear that what is now a virus that latches onto receptors located on the outside of endothelial cells will transform into one capable of attaching itself to the alveolar cells of the lungs. That seems a genetic leap so dire and difficult to imagine that I am prepared to put it on a back burner for the moment.

On Sept. 10, I participated in a briefing on Ebola for the Joint Chiefs of Staff, at the request of Chairman Gen. Martin Dempsey. It was clear to me that Dempsey embraced the challenge of tackling Ebola, and recognized that the virus's spread signaled the need for a swift response. But many issues now require rapid U.S. military reactions, not the least of which is the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) in the Middle East. Dempsey and the Joint Chiefs were struck by the unprecedented appeal for U.S. military engagement delivered by the Nobel Peace Prize-winning Doctors Without Borders (also known by its French acronym, MSF). Never before had the typically pacifist, neutral humanitarian organization asked for military assistance, but the Ebola epidemic has exhausted MSF's capacities, and compelled radical policies.

I provided the Joint Chiefs with a seven-page strategic plan for military action to fight the epidemic, and learned a great deal regarding the potentials and limitations of U.S. capabilities. I likened the scale of need to that of the American military response in Aceh, which featured more than 12,000 uniformed personnel working in immediate disaster relief and longer-term reconstruction of the devastated region. While Operation United Assistance does not embrace all of the details or scale I proposed, it is a bold leap. With the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) in the lead, the effort will combine civilian and military components, as follows:

- The U.S. Africa Command (Africom), will deploy Maj. Gen. Darryl A. Williams to Monrovia, Liberia, where he will lead a team establishing a command center for all military response, working alongside USAID and the United Nations. All of these responders will, of course, toil at the behest and permission of the government of President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf.

- The key elements of military response will focus on logistics, supplies, engineering, support for the Accra, Ghana, "air bridge" for transport of supplies and personnel to the epidemic, and the construction of at least 17 new hospital facilities designated for Ebola care.

- The military will also build a training facility, which will rapidly teach infection control and self-protection procedures to hundreds of local and foreign health workers. The military hopes to process up to 500 health workers, both civilians and humanitarian responders, in a week.

- Though the White House states that up to 3,000 military personnel will be engaged in these activities, the Pentagon tells me no estimate of the scale of operations can be known until Maj. Gen. Williams and his team complete a needs survey in Liberia.

- The civilian side of the operation will feature further expansion of CDC deployment of epidemiologists and laboratory workers, primarily in Liberia.

- The U.S. Public Health Service will provide medical staff for a Department of Defense-built 25-bed hospital in Monrovia. And USAID, partially with the financial support of Microsoft billionaire Paul Allen, will make and distribute 400,000 home care kits to Liberia, to be used by families to tend safely to ailing loved ones.

When I addressed the Joint Chiefs, I stressed the need for speed, and was surprised to learn how long it takes to mobilize such things as makeshift hospitals and the delivery of protective suits. None of these efforts will be accomplished during the month of September, and few will be operational before the end of October. This time frame is not a matter of foot-dragging or a reflection of complacency — on the contrary, Gen. Dempsey has ordered maximum haste. But things take time.

(More from Foreign Policy: What's wrong with Hong Kong?)

I feel that time is running out. Unless Obama's announcement can somehow include immediate measures that lead to long-scale escalations in supplies, logistics support, air shipments, and personnel on the group in West Africa, I fear dire consequences by Christmas. The need for speed is true not only of the U.S. government's efforts, but of those promised by the United Kingdom, China, Cuba, France, and every other nation that has announced some form of assistance. The virus is well ahead of the game, holding the end zone in a game that finds the epidemic control efforts bogged down on their own 19-yard line. The game can't even advance to the 20-yard line right now because airlines refuse to land in the afflicted countries, making delivery of personnel and supplies impossible until the Africom joint effort with Ghana brings a fully operational air bridge online through Accra's airport.

Nothing short of heroic, record-breaking mobilization is necessary at this late stage in the epidemic. Without it, I am prepared to predict that by Christmas, there could be up to 250,000 people cumulatively infected in West Africa. At least 30 nations around the world, I dare predict, will have had an isolated case gain entry inside their borders, and some will be struggling as Nigeria now is, tracking down all possibly exposed individuals and hoping to stave off secondary spread. World supplies of PPEs (personal protective equipment, or "space suits"), latex gloves, goggles, booties — all the elements of protection — will be tapped out, demand exceeding manufacturing capacity, and an ugly competition over basic equipment will be underway. The great African economic miracle will be reversing, not just in the hard-hit countries but regionally, as the entire continent gets painted with the Ebola fear brush. Mortality due to all causes will soar in the region, as doctors, nurses, and other health care workers either succumb to Ebola, become full-time Ebola workers, or flee their jobs entirely. Women will die in delivery, auto accident victims will bleed out for lack of emergency care, old vaccine-preventable epidemics will resurge as health workers fear administering them to potentially Ebola-carrying children, and child malnutrition will set in. Lawlessness will rise as Ebola claims the lives of police and law enforcement personnel, and terrified cops quit their jobs. State stability for hard-hit nations will be questionable, or nonexistent.

I hope that all responding states and humanitarian organizations will manage to break records, getting supplies and personnel on the ground in spectacular haste. I hope that they will work under a command structure that is wise and pragmatic.

Most of all, I ardently hope that Christmas will arrive and my comments above will look like the nattering of a crazed Cassandra. I hope that presidents Xi, Obama, Zuma, and Hollande, Prime Minister Cameron, Chancellor Merkel, and their counterparts will have found a way in the next two weeks to vastly increase the global response to this epidemic, create a meaningful command structure to oversee and manage the entire effort, and then aid the beleaguered countries in their post-outbreak recoveries. And I hope that every one of you reading this will be able, as Christmas approaches, to justifiably denounce me as a fearmonger.