The American middle class is no longer safe from poverty — and that might be a good thing

More Americans than ever are vulnerable to economic insecurity. The silver lining is that this means we might actually do something about it.

We tend to think of the poor as a fixed group mired in disadvantage, far removed from the relative security of the middle class. But the truth is that in post-recession America, poverty has become a thoroughly middle-class issue.

More than 46 million people live in poverty, and that's bad enough. But a full 80 percent of American adults experience economic insecurity at some point in their lives, according to a survey by the Associated Press. This is defined as unemployment, spending more than a year receiving government aid, or living below 150 percent of the poverty line.

This grim figure quantifies how severely the middle class has been hollowed out. But there is a silver lining: the increasingly universal experience of economic hardship makes it more likely that we will move to protect people against the vagaries of the market.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

We saw this dynamic play out in the movement for health care reform. Fears of illness, lost insurance, and crippling medical costs cut across American society, strengthening the push for universal and affordable care.

When it comes to poverty, a similar universal anxiety has largely been absent. Traditionally, few middle-class Americans have anticipated that they, too, could find themselves slipping toward the poverty line.

Furthermore, though Americans have been shaken by rising inequality, upward mobility and self-determination are deep fixtures in the American creed. But while belief in the power of bootstraps-driven hard work is empowering during good times, in bad times it mistakenly conflates a volatile economy with personal failings.

Some might recoil at the idea that middle-class interests must be jeopardized before we'll take poverty seriously. But political coalitions behind social welfare programs have always been stronger when they engage the middle class. Medicaid — public insurance for the poor — was passed as an afterthought to Medicare, which insures elderly health care for everyone.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

More recently, the public arguments for ObamaCare often emphasized slowing the cost of health care (which benefits the middle class) more than expanding care to the uninsured.

And in a larger sense, if nearly everyone is economically insecure it makes for more impartial and just policy-making. Political philosopher John Rawls argued that we would distribute resources more equitably if we made policy choices behind an imaginary "veil of ignorance" to our own social status, as if we all faced the risk of being victims of discrimination, poverty, and other ills. With an 80 percent individual chance of experiencing economic insecurity, we edge closer toward Rawls' sense of justice on the issue of poverty.

We already have a decent policy foundation to deal with rising economic insecurity, along with a host of good ideas for how we can do better. In addition to Great Society antipoverty efforts, both ObamaCare and the economic stimulus made important strides against poverty. To do more, we could provide greater income support by expanding the Earned Income Tax Credit — an idea with bipartisan support — or by crafting something like a universal basic income. We could strengthen unemployment insurance in case of job loss, and enact wage insurance against a fall in pay.

To aid struggling parents and poor children, we could expand the Child Tax Credit. We could even give families the choice to receive it in periodic payments, like a child allowance, or else continue using the tax credit as de facto savings by getting one annual refund.

But a robust package of insurance against economic insecurity is possible only if we reckon with the alarming regularity of poverty in the United States. "Only when poverty is thought of as a mainstream event, rather than a fringe experience," says Professor Mark Rank, "can we really begin to build broader support for programs that lift people in need."

Joel Dodge writes about politics, law, and domestic policy for The Week and at his blog. He is a member of the Boston University School of Law's class of 2014.

-

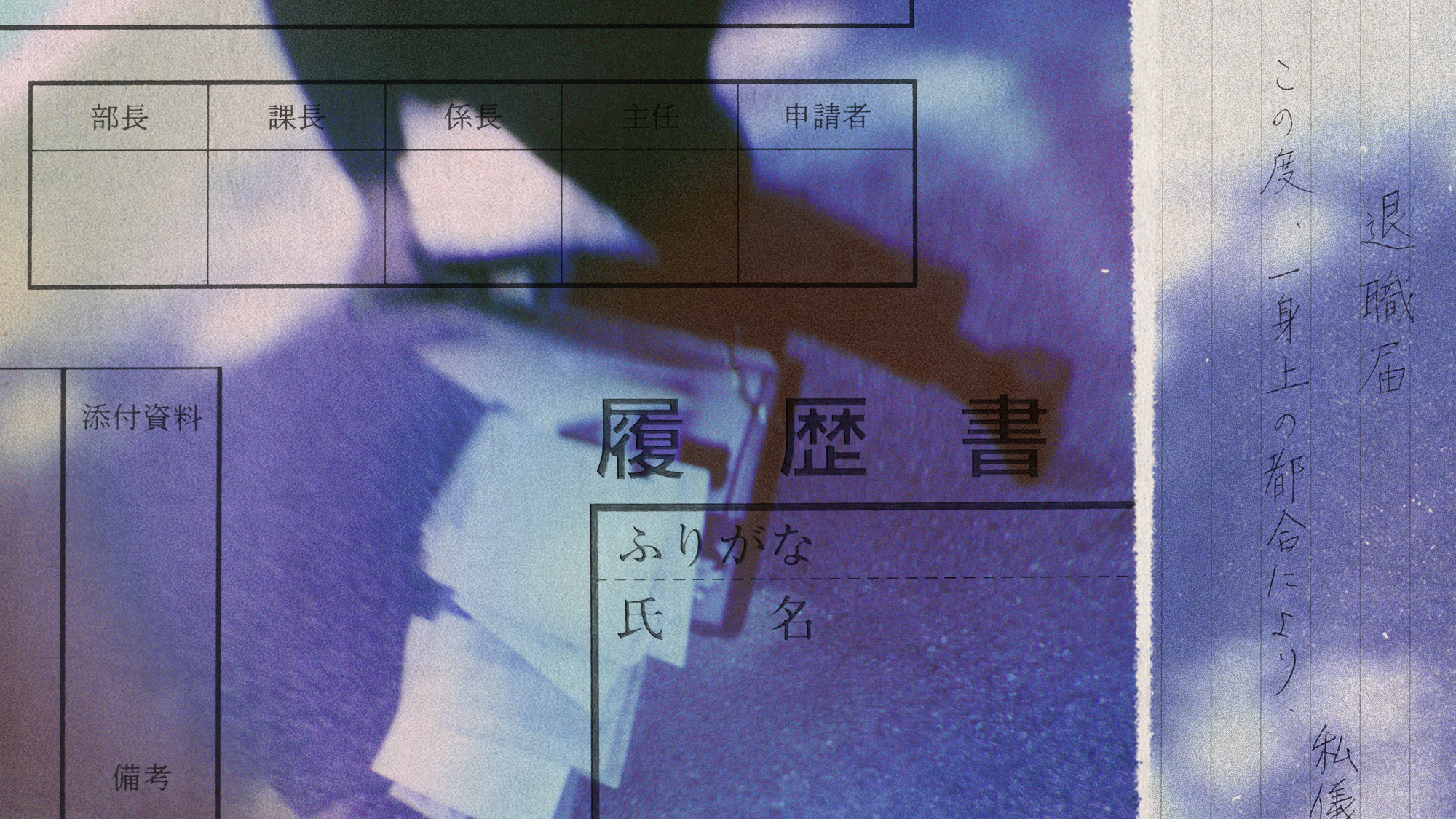

Why quitting your job is so difficult in Japan

Why quitting your job is so difficult in JapanUnder the Radar Reluctance to change job and rise of ‘proxy quitters’ is a reaction to Japan’s ‘rigid’ labour market – but there are signs of change

-

Gavin Newsom and Dr. Oz feud over fraud allegations

Gavin Newsom and Dr. Oz feud over fraud allegationsIn the Spotlight Newsom called Oz’s behavior ‘baseless and racist’

-

‘Admin night’: the TikTok trend turning paperwork into a party

‘Admin night’: the TikTok trend turning paperwork into a partyThe Explainer Grab your friends and make a night of tackling the most boring tasks