The NFL has a domestic violence problem. But America's is worse.

Roger Goodell's wrongheaded priorities are a depressing mirror image of our criminal justice system's

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The NFL and Commissioner Roger Goodell have received heaps of deserved criticism over their utter botching of the Ray Rice case. Before the video of Rice brutally punching his then-fiancée (and now-wife) Janay Rice went public, the former Baltimore Ravens running back had been suspended for only two games. (Once the horrifying tape came out, the Ravens cut ties with Rice, and the NFL suspended him indefinitely.) The NFL's initial lack of severity toward Rice seemed absurd compared with the suspension for Cleveland wide receiver Josh Gordon, forced to sit out for an entire year for marijuana use.

This is par for the course in the NFL. As Andrew Sharp pointed out at Grantland, the NFL has long failed to punish violent offenders, while Nate Jackson observed in The New York Times that the NFL seems obsessed with draconian drug laws.

Sound familiar? It should. Because this inconsistency reflects America's criminal justice priorities.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

We can criticize the NFL all we want — and we should — but we ought to criticize our own government, too. The U.S. is far more interested in fighting the War on Drugs than fighting violence and sexual assault against women.

Take a look at federal spending on the most important program for prosecuting and combating violence against women: the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA). VAWA funding, under the Commerce, Justice, and Science Appropriations budget, provides money for a wide range of programs and services, from legal assistance to transitional housing and research. This graph compares one year's VAWA funding to one War on Drugs initiative, the Drug Enforcement Administration.

Now, this isn't the whole picture. There are other War on Drugs initiatives besides the DEA and other initiatives that address violence against women and in families.

Here is the total federal spending on all of those programs:

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

This comparison is ultragenerous, too: VOCA, the orange strip, is the federal funding for all victims of crime, not just victims of domestic, sexual, or gender-based violence. The green strip is for the Family Violence Prevention and Services Act and other miscellaneous programs under Labor, Health and Human Services like the Rape Prevention and Education funding for the Centers for Disease Control. The War on Drugs estimate includes federal spending on prevention, punishment, and litigation and other costs involving drug-related crime (and is indeed much less than state and local spending on drug crime).

The total? Federal spending against drugs is more than 15 times higher than expenditures aimed at stopping sexual and domestic violence.

Now, this disparity would potentially make sense if it squared with need or demographic reality. But it doesn't come close. In the U.S., one in four women will experience domestic violence during her lifetime; one in five has been raped; one in six has been or will be stalked. Women constitute more than half of the U.S. population, so these ratios result in shockingly high totals. Indeed, these are numbers that are far greater than or at least as large as rates of illicit drug use. Yet the problem receives one-fifteenth of the attention.

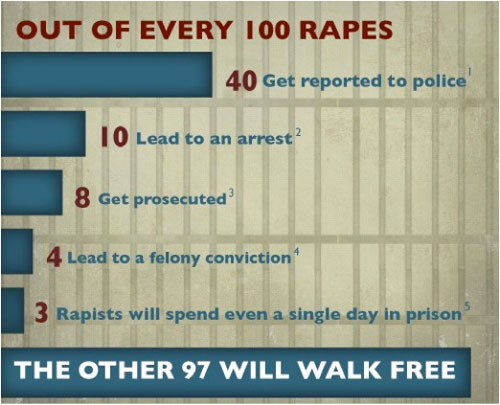

It's not that the government programs addressing sexual and domestic violence are more effective, either. Data from the Bureau of Justice Statistics show that just over half of victims of domestic violence report the incidents to police. Prosecution isn't better: According to the FBI, if a "first-responding police officer conducts a basic domestic violence investigation, 70 percent of the time, prosecutors do not file criminal cases." According to RAINN, the numbers on reporting and prosecuting sexual assault and rape don't inspire more confidence.

These enforcement issues could surely be helped some with greater investment. With more money, we'd surely see personnel better trained to work with victims, labs that process rape kits in a timely manner, expanded protective services and shelters, and more and better prevention programs for potential perpetrators.

The failure to adequately address, prevent, prosecute, and punish sexual and domestic violence is a national disaster. It's even worse when we consider the impact of these crimes versus that of drug use. Though there are attendant public issues to the drug trade, drug use is fundamentally a consensual act: The user is affecting himself or herself. It is, in a way, a "victimless" crime. Domestic and sexual violence is nonconsensual by definition: There is always a victim. If anything, we should be devoting far greater resources to these crimes than to drug crimes, not a tiny fraction. Instead, we choose to sentence people to life terms for nonviolent drug offenses, while domestic abusers and rapists regularly act with impunity.

Maybe it takes the incompetence of the NFL to help us realize this. I think we've already felt part of the injustice: It's why we are so outraged when Josh Gordon gets a one-year ban while Ray Rice is initially suspended for only two games.

So let's condemn the league's handling of the Ray Rice case and seek better policy and programs. But remember: Its failure has been as American as football itself.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day