It's not (always) the teacher's fault: What 'no excuses' reformers get wrong about education

Dana Goldstein's excellent The Teacher Wars offers some useful lessons for those who want to transcend an age-old policy dispute

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

What if we've got education reform all backward? That's the question posed by Dana Goldstein's fantastic new book, The Teacher Wars, which traces the history of education in America over the past 200 years.

Recounting our perpetual angst over the makeup and quality of the teaching profession, Goldstein suggests that we've put too much weight on top-down reform at the expense of grassroots-level empowerment of excellent teachers. She wants to move beyond education reform as we've known it and provides some important lessons for today's reformers along the way.

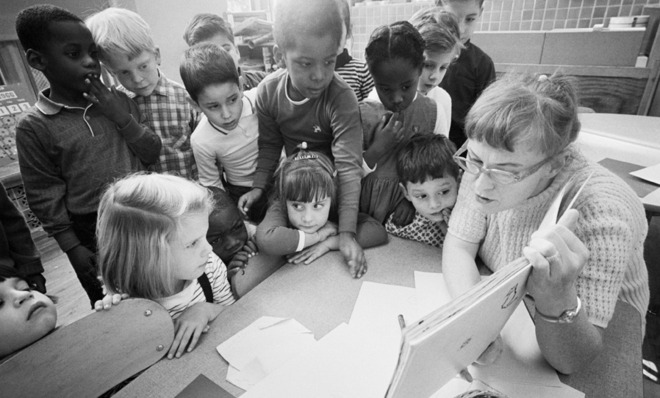

The roots of our current policy debate can be found in the 1960s. Academic researchers showed that the achievement gap between middle-class and low-income students was almost entirely explained by out-of-school factors like student socioeconomic status. This bolstered resistance to reform — particularly reform that held educators accountable — among teacher unions. After all, if achievement is mostly a product of demography, why should a teacher be held responsible for large societal forces like poverty and inequality?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

But there's an important proviso to this research, and it forms the backbone of what has become a "no excuses" philosophy of education reform: Elite teaching can overcome this demographic-driven gap. Researchers have found that "high-quality instruction throughout primary school could substantially offset disadvantages associated with low socioeconomic background."

To many reformers, this shows that no excuse — including economic disadvantage — should justify low student achievement. Wendy Kopp, the founder of Teach for America, which recruits Ivy League graduates to live and teach in disadvantaged communities, declared that "education can trump poverty" if teachers accept their performance as the "key variable" behind student achievement.

Goldstein is suspicious of this "ideal of the all-powerful individual teacher." She devotes special attention — and some skepticism — to TFA and its close cousin in today's reform movement, charter schools. She praises TFA for making low-income teaching a prestige position but resists its no-excuses philosophy.

To be sure, a reasonable dose of the no-excuses attitude has value in the classroom. It keeps demographic fatalism at bay and wards off diminished expectations among teachers and students alike.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

And reformers aren't naïve: Many understand that achievement is a product of more than just great teaching. Geoffrey Canada's much-heralded Harlem Children's Zone provides wraparound social services to families and students enrolled in its Promise Academies, including free prenatal care and child-rearing lessons for new parents. Given the Obama administration's efforts to replicate Canada's organization across the country, reformers and policymakers both clearly realize that social welfare also has an important role to play in shaping student achievement.

Still, Goldstein levies some important critiques against the no-excuses movement. Without moderation, its strict brand of instruction can make for an unduly oppressive classroom environment. Goldstein watched a student get punished for "speaking out of turn" when he eagerly answered "Yes!" to a rhetorical question in a young TFA recruit's lesson. Classroom discipline is undoubtedly important, but overly stern instruction can stray into killjoy militancy.

There's also the possibility that reform-driven school closures will only exacerbate the achievement gap. "[N]eighborhood school closings and school 'reconstitutions' as charter or magnet schools," Goldstein explains, "lead disproportionately to the loss of teaching jobs held by African- Americans." Good middle-class jobs are already hard to come by in poor black neighborhoods, and the loss of teaching positions worsens economic conditions in the very communities that reformers are trying to serve. This deepens the socioeconomic disadvantage that educators must overcome.

This may be a cost worth enduring to shutter the truly unsalvageable schools that persistently disserve their students. But it's a cost that reformers must reckon with before urging that drastic step.

Reformers might also be endangering their cause by placing an unsustainable workload on teachers. In their urgency to conquer education inequality, no-excuses charter schools commonly call on teachers to "work 12 hours a day, hold weekend test-prep sessions, and be available at all times by email or phone," Goldstein notes. This hastens teacher burnout and increases the likelihood that teachers will seek union protection, jeopardizing the very autonomy that many charters hold dear.

In her final chapters, Goldstein embraces a package of reforms that warrants real consideration: expanding teacher peer observation and mentorship opportunities, cultivating a diverse array of charters and innovative experimental schools, renewing our commitment to voluntary desegregation, and more. Her book envisions a promising new era of school reform that doesn't stir a panic over underperforming teachers but rather amplifies the influence of exemplary ones.

But first, to leave behind the sclerotic debates that have long defined American education reform, we must transcend the teacher wars altogether.

Joel Dodge writes about politics, law, and domestic policy for The Week and at his blog. He is a member of the Boston University School of Law's class of 2014.