It doesn't matter how rich the rich are

Money buys secrecy, so we'll never know how rich the rich are. But that's beside the point.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

A very large slice of the economic conversation this year has been dominated by the topic of inequality, especially in regards to Thomas Piketty's magnum opus Capital in the 21st Century.

But it's hard to know how much of a problem economic inequality is without knowing how fast it's rising or falling and how unequal society is overall. The problem of measuring inequality has unsurprisingly been a point of contention regarding Piketty's book, specifically in the spat between Piketty and Chris Giles of the Financial Times.

The big difficulty with inequality as a measure is that the rich don't want other people to know how rich they are, and being rich, they have the means to jealously guard that information. And that isn't just out of a desire to pay as few taxes as possible (although that is almost certainly a major reason). It's also for security reasons and the desire to avoid the wrong sorts of attention — extortionists, kidnappers, robbers, etc.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

So, the rich hide their wealth not just behind the walls of gated communities, intricate alarm systems, and security guards. They also hide their wealth behind an increasingly sophisticated apparatus of trust funds, foundations, shell corporations, and tax havens.

Recent research suggests that inequality researchers have systematically underestimated how rich the rich are. Inequality researchers typically turn to survey data to estimate the wealth of the wealthy. But, according to a paper by Philip Vermeulen of the ECB, there are big gaps between such survey data and more objective measurements, in this case, publicly available records of company ownership maintained by Forbes.

In the U.S., survey data showed the top 1 percent controlled 34 percent of the nation's wealth, less than the 37 percent suggested by company ownership records. In Austria, the gap was bigger — the top 1 percent controlled 23 percent per the survey, to 36 percent per ownership records. In Germany, the gap was 9 points — the top 1 percent controlled 26 percent per the survey, to 35 percent per ownership records.

And that is just the picture painted by publicly available data. The real picture — one that factors in the wealth held in privately held corporations, trust funds, foundations, and other uncounted reservoirs of wealth — may show much higher inequality still.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

But I don't think that's the real problem.

Focusing on how immeasurably rich the rich may be is putting the cart before the horse. The impoverished do not suffer because the rich are rich. Economics is not a zero sum game. There is not a predetermined amount of wealth in society to be divvied up and redistributed. More is constantly being created. The poor suffer because they lack wealth and access to economic opportunities. In other words, we need to focus on what the bottom doesn't have, not what the top does.

I think too much is made in the policy debate about the gap between rich and poor. To be sure, it's an effective political strategy to point out how wealthy the wealthy are when trying to raise taxes to fight poverty. But let the politicians be tactical.

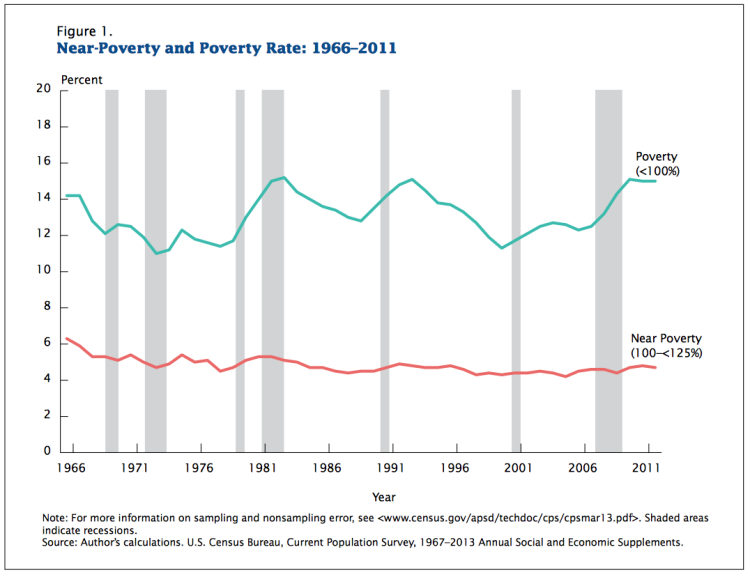

So how bad of a problem is poverty? Well, according to the U.S. Census, America has not succeeded in reducing poverty over the last 50 years. It's gone up and down over that period. Indeed, in the wake of the financial crisis and recession there has been a large spike upward in both what is defined as poverty as well as a smaller rise in what is defined as living close to poverty:

(U.S. Census Bureau)

That is, to say the least, disappointing and a sign that the U.S. needs to seriously re-examine its approach to poverty. We need to get much, much more serious about helping the poor get out of it.

But globally, at least, there has been a steep decline in poverty over the last half century. That, in the bigger picture, matters much more than disputes over just how rich the super rich really are. Long may that decline continue.

John Aziz is the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also an associate editor at Pieria.co.uk. Previously his work has appeared on Business Insider, Zero Hedge, and Noahpinion.

-

Quentin Deranque: a student’s death energizes the French far right

Quentin Deranque: a student’s death energizes the French far rightIN THE SPOTLIGHT Reactions to the violent killing of an ultra-conservative activist offer a glimpse at the culture wars roiling France ahead of next year’s elections.

-

Secured vs. unsecured loans: how do they differ and which is better?

Secured vs. unsecured loans: how do they differ and which is better?the explainer They are distinguished by the level of risk and the inclusion of collateral

-

‘States that set ambitious climate targets are already feeling the tension’

‘States that set ambitious climate targets are already feeling the tension’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day