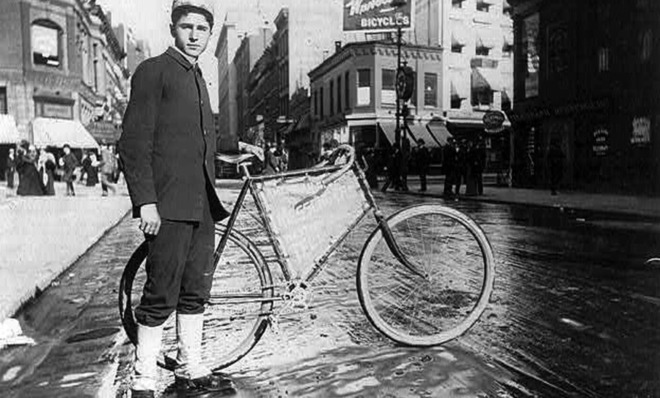

The high fashion of 19th-century cycling

"I cannot repeat too often that, in matters cycular (sic), STYLE IS PRACTICALLY EVERYTHING; without it, strength is wasted, appearance sacrificed, and pleasure lost."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

On the sunny and cool afternoon of June 17, 1896, a parade was held in Brooklyn celebrating the opening of the Ocean Parkway cycle path. At one p.m. sharp, the inimitable sound of ten thousand approaching bicycles filled the air. Spearheading this procession was the noted rider Charles H. Luscomb of the Thirteenth Regiment, accompanied by a military entourage of three hundred militiamen. They were swiftly followed by the uniformed personnel of more than thirty cycling clubs drawn from across the region, including the Amsterdam Wheelmen and the Ninth Ward Pioneer Corps. Next came the serried ranks of the League of American Wheelmen, the largest cycling organization in the country with more than 100,000 members. Concluding this cavalcade were thousands of "unattached" cyclists ranging from gaily-bedecked children to fashionable couples, whisking their way down the boulevard on their "silent steeds," past the undeveloped meadows of central Brooklyn until finally reaching the sun, surf and sand of Coney Island.

This was the most magnificent cycling parade New York City had ever seen, a celebration of the country's first bicycle path, opened to answer the demands of the expanding crowd of New Yorkers with wheels. For in the mid-1890s, New York was the "Metropolis of cycledom," in the words of the Brooklyn Eagle, home to 250,000 bike-owning citizens (or one out of every twelve New Yorkers), ten cycling journals, fifty-five cycling clubs in Manhattan alone, twenty-nine cycling academies, and cycling racks everywhere from Madison Square Garden to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The earnest debates on the moral and political consequences of cycling were held in esteemed newspapers and at great public meetings.

And yet, no more than five years later, the bicycle would be abandoned by Gotham's citizenry as quickly as it had been taken up. It would remain out of fashion for most of the next century, until it became object of a new, but markedly similar, craze; a fin de cycle story that should serve as both an inspiration and a warning to riders and cycling advocates today.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

(More from Narratively: Reinventing the oldest profession)

In the 1880s, bicycles had attracted small groups of dedicated practitioners, but the product's poor safety record, extensive learning curve and relative obscurity kept the ranks of wheelmen limited. The invention of the "safety" bicycle in the late 1880s, however, changed this; its two same-sized wheels were a much more stable frame than the tottering "high-wheel," dramatically reducing the danger and difficulty of cycling. The bicycle's popularity within the Continent, particularly in ever-fashionable Paris, imbued the product with a measure of prestige and glamour it had never before enjoyed. It became a must-have status symbol. In 1898, one Frances Abbott, quoted in The North American Review, remarked: "I have lived to see the woman who never wished her daughter to have a bicycle ride a wheel herself in company with that daughter; and when I ventured to recall her former opinions she said with unblushing serenity: 'Oh, well, everybody rides now; the most fashionable people have taken it up; there is really nothing like it,' and she began to chide me because I did not own a wheel."

The bicycle craze was more than just a pure product of fashion and modern mass consumption, however, and it wasn't necessarily an expression of progressiveness. The bicycle was adopted into a middle-class culture (the wheel was far too expensive for most of the working class, at least initially) that remained solidly Victorian in outlook, ridden by people whose perspective was founded upon rigid dichotomies between "right" and "wrong," "man" and "woman," "authentic" and "fake," "respectable" and "not-so-respectable." The bicycle served to bolster these Gilded Age principles in the hands of its users, functioning as a mobile platform on which its owner's genteel credentials could be displayed and proven.

One way of doing this was to buy the most expensive, luxurious and tasteful bicycle and accessories possible. From decorated chain-guards to novelty cycling bells to handle-bar revolvers, consumers spent more than $200 million on bicycle sundries in 1896 alone, as opposed to only $300 million on the bicycles themselves that same year. Nowhere did the consumer culture surrounding the bicycle manifest itself more than in the area of attire. By sporting the latest styles, wheelmen and women sought to project a public image of taste and wealth for their peers to appreciate. In 1898, The New York Times wrote that "Sweaters…will probably be seen but little among the better class of riders this year, as the extra comfort gained by their wear is considered more than offset by the impossibility of preserving a spruce appearance when wearing them." A well-meaning author pressed home the point in The American Cyclist, declaring that "I cannot repeat too often that, in matters cycular (sic), STYLE IS PRACTICALLY EVERYTHING; without it, strength is wasted, appearance sacrificed, and pleasure lost."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

(More from Narratively: The BMX boys of E.T.)

Style was at the center of the cycling promenades and parades that drew thousands of riders and even greater crowds of spectators to the boulevards of the city throughout the mid-to-late 1890s. The most popular setting for these displays was Riverside Drive — the "paradise of bicyclists" in New York, as Harper's Weekly labeled it in 1894. The New York Times reported that "the Sunday procession of cyclists has got to be one of the sights of the city," and the great collections of cyclists who gathered every weekend was described by reporters as a kind of formal spectacle — a "procession," a "pageant," a "parade." Such terms were a result of the emphasis on presentation and display that, above all, distinguished middle-class cycling from more utilitarian travel.

But decorum and propriety had to be satiated as well, and too much tactless display simply would not do. The Brooklyn Eagle warned potential parade-goers that "no fancy or fantastic costumes will be allowed in the line. Bicycle riding is a matter of common sense, and it should not be brought into ridicule by the fantastic notions of any few individuals who may have adopted it." And while much has been made of the liberating effects of cycling on women's dress — iron corsets and unwieldy skirts were disregarded in favor of more form-fitting, sensible wear while a-wheel — such attires would hardly raise hackles among the Lubavitchers of Williamsburg today.

Along with their appearance, the comport and activities of cyclists were subject to genteel regulation. "Scorching," or riding extremely fast, was seen as not only dangerous, but a sign of low-class loutishness. The New York Times reported that "with the cheapening in the cost of bicycle riding in the public streets has come the abuse of that privilege by thousands of ignorant and loaferish individuals… irresponsible and reckless young men to whom a stable keeper would not entrust a saddle horse, and who are not fit to ride anything but a rail." Several dozen cycling schools and innumerable etiquette guides were produced which would help the wheeled bourgeoisie not only learn to ride, but "ride right."

(More from Narratively: The liberty factory)

The bicycle was a private vehicle in public space, and hence a topic of moral and political import. Opponents of the bicycle claimed that the wheel undermined morality (amongst other things, by enabling young women to venture great distances without supervision), caused noise and interfered with traffic. Conversely, bicyclists claimed that "the more ignorant, uncultured, and generally illiterate and 'countrified' the man is, the more bitter is his hatred of the bicycle" — and lobbied for bike-friendly legislation, paved roads and additional bicycle lanes. (Sound familiar?) The Brooklyn Eagle declared in 1896 that "thousands of men, women and children who ride on bicycles are aware that they have the same right in the roads and streets and alleys of this country that the walker and horseback rider and wagon and truck driver enjoy." Through the efforts of the League of American wheelmen and several other clubs, many of New York's cobblestone streets were made more bike friendly through the mid-1890s by being paved with macadam — single layers of small stones — along with some of the first dedicated bicycle lanes in the country.

Read the rest of this story at Narratively.

Narratively is an online magazine devoted to original, in-depth and untold stories. Each week, Narratively explores a different theme and publishes just one story a day. It was one of TIME's 50 Best Websites of 2013.

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl: A win for unity

Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl: A win for unityFeature The global superstar's halftime show was a celebration for everyone to enjoy