Why are food prices skyrocketing?

No, you can't blame the Fed

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

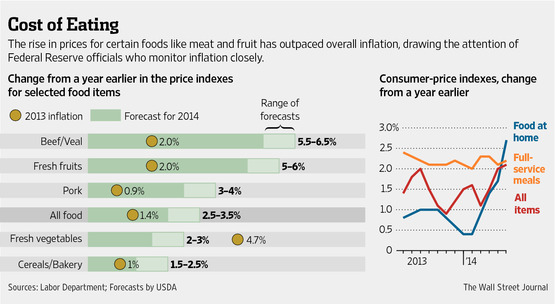

In 2014, food prices for Americans have been soaring, as this graph from The Wall Street Journal illustrates:

(WSJ)

That far outpaces overall inflation, which is running at a more tame 2.13 percent, very close to the Fed's 2 percent inflation target.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

While food only accounts for 13 percent of Americans' spending, rising prices are still a painful prospect for everyone, and especially for lower-income Americans, for whom food costs make up a larger proportion of their costs.

So, who or what is to blame? Well, there are a lot of factors in play that have sent certain food items soaring.

Coffee prices have climbed thanks to unseasonably dry weather in Brazil. Drought in Oklahoma and Texas is driving up beef prices. Wheat prices have been boosted by geopolitical uncertainties — after rising because of the extreme cold winter in the U.S., they were pushed higher by the crisis in Ukraine, a key grain producer.

The porcine epidemic diarrhea virus has devastated hog farmers, contributing to higher pork prices. Another disease known as citrus greening is killing Florida's orange and grapefruit trees, driving up citrus prices. Shrimp prices have been pushed up by a bacterial infection in South East Asia that has wreaked havoc on stocks.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Some food prices have also been bolstered by high demand in emerging markets such as China and Russia, where rising incomes and the emergence of a new middle class have increased consumption of dairy products, as well as meat.

The good news is that these factors will subside, eventually. The transitory weather-related factors will subside — and even if (due to climate change) the future brings many more such events, producers can adapt, for example by growing crops in climate-controlled greenhouses. And rising global demand from the new global middle class for meat and dairy will be met with rising global supply of those products from producers seeking a bigger slice of profitable market share.

The bad news is there's very little that can really be done about it right now. One (incorrect) view is that the sharply rising food prices are the Fed's fault, caused by its ultra-easy monetary policy, and that the Fed should hike rates soon to get ahead of the inflation.

But this view ignores the reality that overall inflation is much lower than food price rises. That's because the factors pushing certain food prices up are transitory, and only relate to specific foods, rather than being a general monetary phenomenon (as inflation became in the late 1970s and early 1980s). For example, the prices of lots of other things like used cars and trucks, piped gas, and fuel oil are currently falling.

The point of ultra-easy monetary policy is to incentivize investment. It does this through imposing a cost (negative real interest rates) on sitting on cash, encouraging businesses and entrepreneurs to invest (and consumers to spend) instead of waiting as their purchasing power erodes. Hiking interest rates now would just curb that investment, including the investment necessary — in food production, food technology, and infrastructure — to allow global food supply to rise to meet demand and bring food prices under control.

Fortunately, the Fed has shown no interest in hiking interest rates at that this point, with Fed chair Janet Yellen rightly arguing that "the data that we're seeing is noisy."

So if the Fed can't (and shouldn't) do anything about rising food prices, who should?

Well, until market forces deal with the food price problem, there is a way to help the poorest Americans who are being hurt the most by the rising food prices. That would be to link the monetary value of food stamps (SNAP) to food price inflation, so that when food prices rise the purchasing power of food stamps is pushed up by an equal amount. But rising food stamps spending would either require borrowing more money, or taxing the rich more to help the poor, two things Congress seems to have absolutely no interest in doing.

John Aziz is the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also an associate editor at Pieria.co.uk. Previously his work has appeared on Business Insider, Zero Hedge, and Noahpinion.

-

The EU’s war on fast fashion

The EU’s war on fast fashionIn the Spotlight Bloc launches investigation into Shein over sale of weapons and ‘childlike’ sex dolls, alongside efforts to tax e-commerce giants and combat textile waste

-

How to Get to Heaven from Belfast: a ‘highly entertaining ride’

How to Get to Heaven from Belfast: a ‘highly entertaining ride’The Week Recommends Mystery-comedy from the creator of Derry Girls should be ‘your new binge-watch’

-

The 8 best TV shows of the 1960s

The 8 best TV shows of the 1960sThe standout shows of this decade take viewers from outer space to the Wild West