No, war doesn't boost economic growth

The evidence suggests you should give peace a chance

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Tyler Cowen argues in The New York Times that "the lack of major wars" is hurting economic growth:

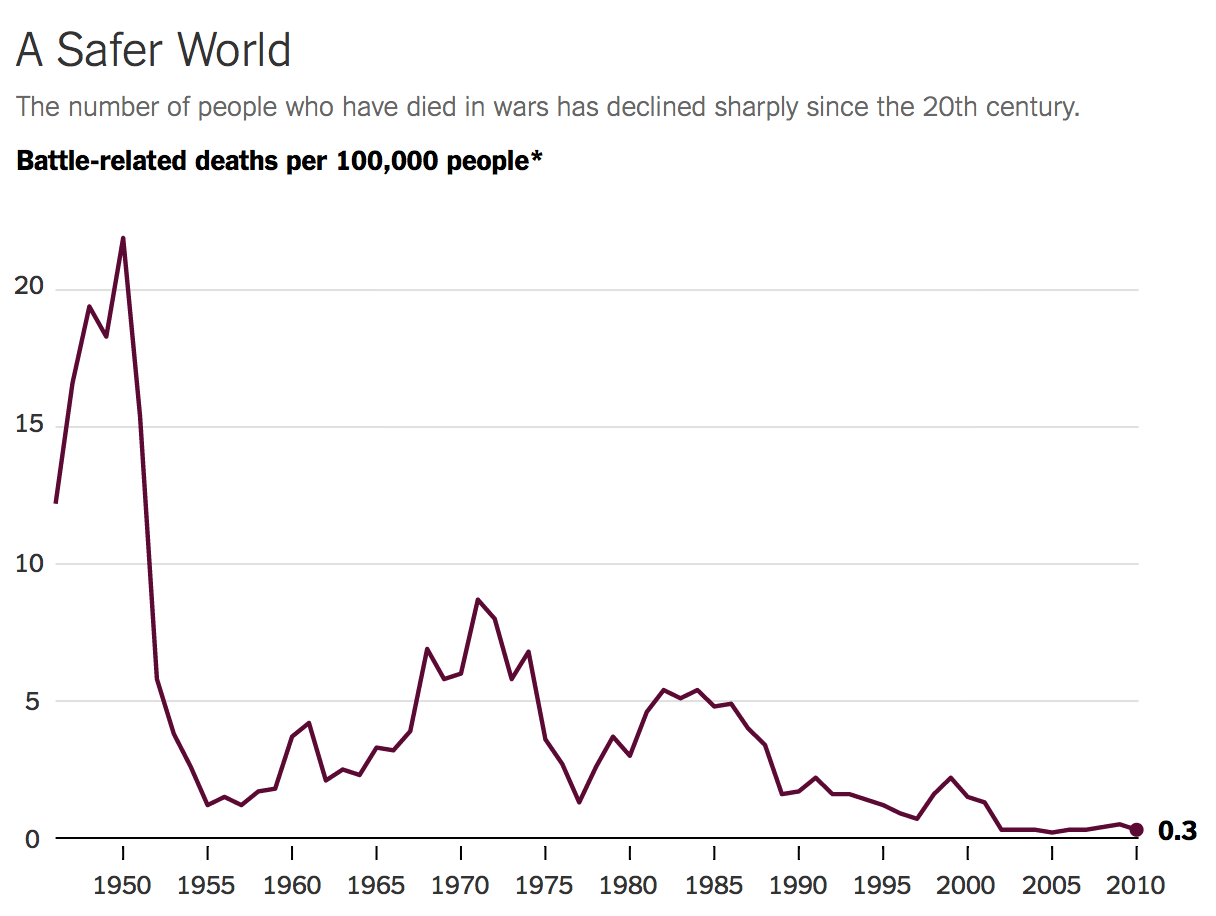

The world just hasn’t had that much warfare lately, at least not by historical standards. Some of the recent headlines about Iraq or South Sudan make our world sound like a very bloody place, but today’s casualties pale in light of the tens of millions of people killed in the two world wars in the first half of the 20th century. Even the Vietnam War had many more deaths than any recent war involving an affluent country.

Counterintuitive though it may sound, the greater peacefulness of the world may make the attainment of higher rates of economic growth less urgent and thus less likely. [The New York Times]

It's a pretty intriguing argument. It seems reasonable to claim that the prospect of war could give people a greater sense of urgency, and thus fire economic growth. Cowen reasons: "the very possibility of war focuses the attention of governments on getting some basic decisions right — whether investing in science or simply liberalizing the economy."

The trouble is that the evidence shows the opposite. Cowen's article centers on this chart from Steven Pinker that shows the significant decrease in war deaths in the period following 1950:

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

(New York Times /Steven Pinker, based on data from the Human Security Report Project at Simon Fraser University)

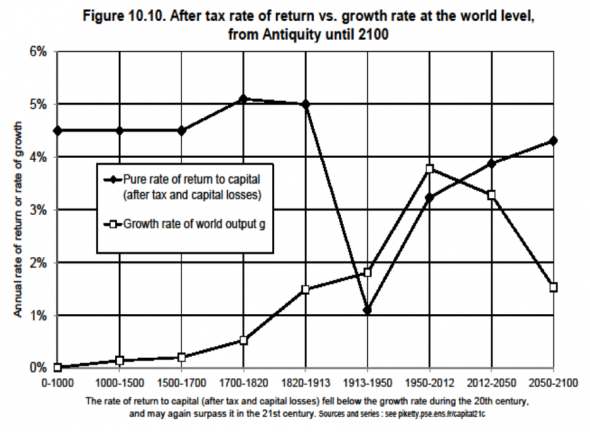

But as this graph from Thomas Piketty's Capital in the Twenty-First Century shows, the highest period in human history for average yearly economic growth has been this most recent period, from 1950 to 2012, during which war deaths severely decreased. (Note that the last two data points in the line are projections)

(Thomas Piketty, Capital in the Twenty-First Century)

If the prospect of war is supposed to spur economic growth, you'd think that the period of 1913-1950 — one of the bloodiest periods in human history during which an estimated 81 million died in World War I and World War II combined, not to mention the estimated 9 million that died in the Russian Civil War of 1917-1922 or the estimated two million that died during the Mexican Civil War of 1910-1920 — would have eclipsed the relatively more peaceful years that followed. But it didn't. The more peaceful world that has emerged since 1950 has exhibited the highest level of economic growth in human history.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Stretching back further into the past, Piketty's data show that growth was much worse still. While Pinker's graph of war deaths does not extend back past the 1940s, it's pretty clear that the low-growth, pre-modern world was at war much more often, and much more violently.

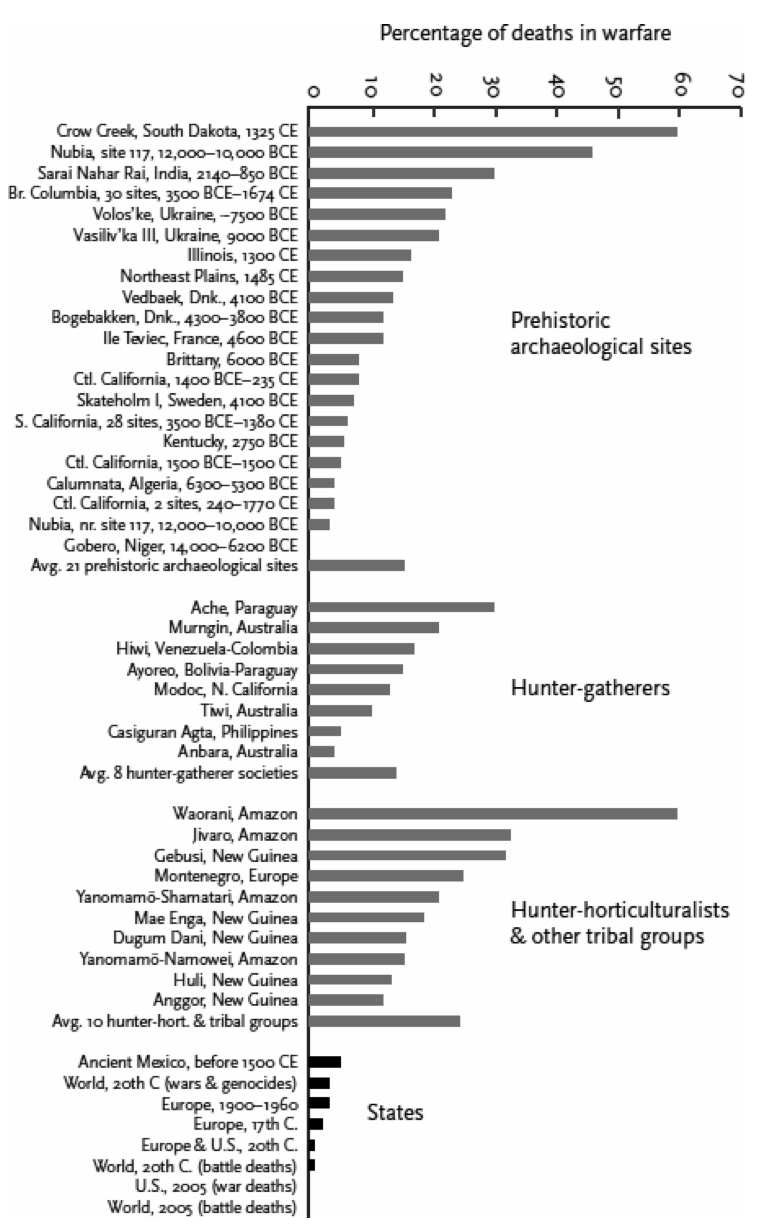

Life in the pre-modern world was nasty, brutish, and short for most, with life expectancy hovering between 20 and 30 until modernity. Estimates in Pinker's book suggest that in some societies up to 60 percent of deaths were from war, orders of magnitude greater than today:

(Stephen Pinker, The Better Angels of Our Nature)

So the pattern is clear. Pre-1950: lots of wars, less growth. Post-1950: decreasing numbers of wars, considerably more growth.

That doesn't mean that Cowen's logic about war spurring urgency is wrong, exactly. I bet if Genghis Khan's Mongol horde was coming to pillage your village, you would pretty urgently start forging weapons and erecting defenses. That's economic growth!

But this urgency is likely outweighed by other factors, like the Mongol horde slaughtering the labor force, razing cities, and salting the earth. Even if you win the battle, you may suffer casualties, injuries, and economic damage, like destroyed weapons, destroyed infrastructure, crop destruction, and dead livestock. Capital cannot multiply if it is destroyed. Economic growth is meaningless if it just ends in mass destruction. And that seems to have been the pattern that played out in the pre-modern world.

Of course, post-1950 the world has still spent an awful lot on military spending, which is where I can find some common ground with Cowen. He argues:

Fundamental innovations such as nuclear power, the computer, and the modern aircraft were all pushed along by an American government eager to defeat the Axis powers or, later, to win the Cold War. The internet was initially designed to help this country withstand a nuclear exchange, and Silicon Valley had its origins with military contracting, not today’s entrepreneurial social media start-ups. The Soviet launch of the Sputnik satellite spurred American interest in science and technology, to the benefit of later economic growth. [The New York Times]

The key has been that these innovations have had lots of civilian applications — like the laptop computer connected to the internet that I am currently typing into — and the destruction and deaths of war have occurred at a much lower rate than in the pre-1950 world. Especially in the West we have increasingly had the economic boosts of military buildup without as much actual war. But the world has actually come pretty close to disastrous nuclear hellfire a few times, from the Cuban missile crisis, to the Goldsboro plane crash of 1961 (where a hydrogen bomb was accidentally dropped on North Carolina but failed to detonate), to the 1983 Soviet nuclear false alarm incident.

Nevertheless, worrying about war has mostly failed to spark sustained economic growth for most of human history. And the only period in which it lived up to the hype was one where we had large-scale military buildups with considerably less actual war (even if the threat was more terrible than ever).

That means that if we want to "get urgent" and spur higher growth, we really should find other things to be urgent about. Like, for example, eradicating poverty, curing diseases, colonizing space, or as my colleague Ryan Cooper suggests, developing renewable energy and preventing climate change.

John Aziz is the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also an associate editor at Pieria.co.uk. Previously his work has appeared on Business Insider, Zero Hedge, and Noahpinion.

-

Health insurance: Premiums soar as ACA subsidies end

Health insurance: Premiums soar as ACA subsidies endFeature 1.4 million people have dropped coverage

-

Anthropic: AI triggers the ‘SaaSpocalypse’

Anthropic: AI triggers the ‘SaaSpocalypse’Feature A grim reaper for software services?

-

NIH director Bhattacharya tapped as acting CDC head

NIH director Bhattacharya tapped as acting CDC headSpeed Read Jay Bhattacharya, a critic of the CDC’s Covid-19 response, will now lead the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention