Should you buy stocks now?

Yes, if you have the patience to buy and hold for the long term

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Sean Davis at The Federalist angrily calls me a "financial illiterate with little to no understanding of risk."

Why? Last week, I wrote an article lamenting the investment behavior of young people today. Just 27 percent of 18- to 29-year-olds reported owning shares in individual companies or as part of a fund, down from 33 percent in April 2008, according to the latest Gallup poll on the matter. That means that the vast majority of millennials have missed out on a market that has very strongly rebounded from its 2008 lows.

Sure, lots of young people aren't investing because they're unemployed, or because they just don't have the money. Unemployment is an extremely serious problem, and I have long argued that America as a whole — and the government in particular — should take fighting unemployment and especially youth unemployment much more seriously.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

But I presented evidence to show that even those with the money to invest are averse to stocks, and prefer to sit on cash. Davis interprets this as me telling millennials to "buy at the top" and advocating that they "should immediately dump what precious little cash they have in the market — on the fact that the market has recently appreciated and is currently at or near all-time highs." He calls this "monumentally stupid advice".

But my argument for investing in stocks has nothing to do with their current price, and everything to do with the fact that putting your money in productive businesses that give a return to investors will produce much, much better returns in the long run than sitting on cash, which does absolutely nothing and which is what an embarrassingly large number of millennials with money are choosing to do. Warren Buffett makes the same argument, and for good reason — investing in productive businesses for the long term is how he got rich.

Obviously it would have been better for millennials who had the money to invest to get their money into stocks at lower prices than today. There were ample chances to do that in the last five years.

For those investing today, there is always a chance that next year the price of stocks will be cheaper than now, providing a better opportunity to buy. But markets that make new highs do tend to go higher still, so there is also a strong chance that stock prices will continue to appreciate, and that people who wait until next year, the year after that, or the next market bottom will have to pay more than the current price. And people who wait will miss out on the dividends between then and now — and as I will explain, the compounding dividends are what make stocks such a great investment.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Davis continues that stocks are a risky bet, and that an investor in stocks at the start of the millennium would so far have yielded a little over 1.4 percent per year — a tiny return, considering the risks: "what did the average equity investor (gross of fees, mind you) get in return for the massive risk he or she assumed since the beginning of the 21st century? Roughly 1.5 percent a year over 14 years. From March of 2000 through mid-2013, an investor in a simple corporate bond index would have outperformed an individual who invested in an index fund that tracked the S&P 500."

This is a grotesque misinterpretation of how investing in stocks works. If Davis wants to know what financial illiteracy looks like, he should look in the mirror.

Here's what Davis so obviously misses: the compounding power of dividends. When you invest in stocks, you don't just get to keep gains in price, but from dividends paid to shareholders. Davis' calculation only took into consideration the former, not the latter.

And when you consider the total return (including dividends) of the S&P 500 over the time period from March of 2000 that Davis looks at, stocks are up 77.53 percent, translating into healthy gains of 5.17 percent per year:

[YCharts/Standard & Poors]

That's the giant difference that dividends make. And that is over a 15-year period that featured two big market crashes, including the worst one since the Great Depression. From June 1988 — the earliest the publicly-accessible total return data goes back to — you get an 1160 percent gain, or an extravagant average of 44.61 percent per year.

Obviously stocks have risks. Although diversification (typically through owning an index fund rather than individual companies) reduces the risks, the high returns on stocks are a return for risk and a return for patience. Markets can panic, and the price of stocks can fall dramatically in the short term. Investing is about holding for the long term, and giving the companies you've invested in the chance to realize a return. Buying stocks for short term gains is little more than gambling.

Now, I don't know whether the next 26 years will look as good as the last 26. I'm pretty optimistic, not least because of the raft of potentially game-changing innovations coming into the market today — like 3D printing, solar energy, and artificial intelligence. Some of these have the potential not just to drive demand for new products, but also to avert dangerous climate change and resource depletion.

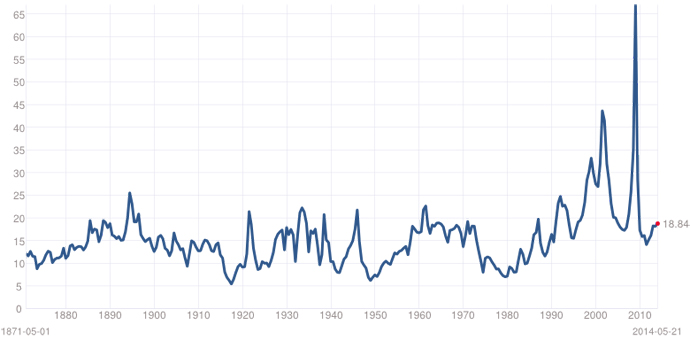

And while prices today might not be cheap relative to the market bottom in 2009, stocks are not obviously overpriced relative to earnings in they way they were during the last two bubbles. Here, the price to earnings ratio since 1880:

Nobody knows the future. If buying and holding through the relatively bad recent years has yielded a pretty decent 5 percent per year — way above inflation and way above current returns on savings accounts — that's where I want my money to be. And history shows that, if you're an investor who wants the best chance of the best long-term return possible, that's where you should want your money to be, too.

John Aziz is the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also an associate editor at Pieria.co.uk. Previously his work has appeared on Business Insider, Zero Hedge, and Noahpinion.