Pope Francis wants Catholics to doubt the Church. He's right.

No one speaks "God." Not even the pope.

Would it be weird to say that the Catholic Church under Pope Francis has encouraged a sense of uncertainty about God?

After all, this is an institution that has devoted centuries to hammering out and polishing an authoritative system of doctrines concerning who God is and what God expects. It claims to have been founded by Jesus Christ and to be guided infallibly by the Holy Spirit. It has warned of eternal damnation if its authority and precepts are ignored or rejected. In other words: If Catholicism is true, you don't want to be in doubt about its teachings. But by giving the impression that longstanding teachings of the faith might significantly change, Pope Francis and other church leaders have invited just such doubt.

No surprise, Catholic writers have expressed concern. Responding to reports that the church might stop denying communion to Catholics in permanently adulterous marriages, Ross Douthat wonders what the appropriate response of Catholics should be to such changes. Michael Brendan Dougherty, mindful of the church's turbulent history, fully expects that a pope or governing council in the church will eventually issue a policy flatly contradicting church teaching — and he believes that most Catholics will be wholly unprepared for it. In such conditions, some among the faithful would doubt the church itself. Lasting heresy or disbelief might take root and grow in this soil.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

According to Catholicism, the core doctrines of the church express absolute truth and therefore cannot be altered, but paradoxically this premise doesn't preclude changes to its teaching. In the parlance of the church, it only means that a previously proposed understanding wasn't really unchangeable doctrine. Still, a big deal. By merely entertaining doctrinal development, the church entices believers to question its authority and the exact content of its faith.

In fact, Pope Francis has explicitly endorsed doubt in the life of faith. In a 2013 interview published in America Magazine, the pontiff said that the space where one finds and meets God must include an area of uncertainty. For him, to say that you have met God with total certainty or that you have the answers to all questions is a sign that God is not with you. Be uncertain, he counsels. Let go of exaggerated doctrinal "security." A devout faith must be an uncertain faith:

The risk in seeking and finding God in all things, then, is the willingness to explain too much, to say with human certainty and arrogance: "God is here." We will find only a god that fits our measure. The correct attitude is that of St. Augustine: seek God to find him, and find God to keep searching for God forever.

The pope has taken a risk with all this, but not without reason. If God really is infinite and indescribable, as Catholicism and other religious traditions imagine, then an uncertain faith makes sense. At the end of the day, those who talk about God really do not know what they're talking about. People refer to God with symbols and metaphors, stories and analogies, believing that these limited expressions disclose a limitless reality, but even if these expressions are true, they nonetheless differ infinitely from any infinite being. Undoubtedly, a lot gets lost in translation.

Trying to understand the full meaning of the words and images one uses to speak about God is like attempting to assess the quality of a translation without knowing the original language. No one speaks "God." Not I. Not the pope. Not even Stephen Colbert. Defending the theological use of metaphors, Aquinas wrote that "what He is not is clearer to us than what He is. Therefore similitudes drawn from things farthest away from God form within us a truer estimate that God is above whatsoever we may say or think of Him." For instance, believers use words like father and mother to refer and relate to God, but without being able to compare and contrast such language with the reality of God, they cannot have a clear sense of the analogies they employ. No one can. Aquinas wrote a lot about God, but he later likened it all to straw. This is the religious condition.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Consequently, religious doctrine has to be understood without the benefit of knowing the whole. As it's only in the context of the whole that one can fully make sense of the parts, the meaning of religious doctrine will always be ambiguous. Imagine readers trying to understand a novel having only a few sentences of the text. They'd have to work with what they have knowing that there's far more to the story and that they might not even have a solid grasp of the few parts they've been able to read. If they discovered additional fragments, they'd have to revise their understanding. If religious believers are serious about the infinity of God, then they should be modest about their doctrines, interpreting and sharing them with conviction and critique, faith and doubt. No one knows what's beyond the horizon.

As Damon Linker has argued, the pope is unlikely to make any major doctrinal revisions given his personality and the institutional limits on the papacy, but simply by encouraging doubt as a necessary aspect of life in the church, he's reminded Christians that, for them, truth is a person and not a set of formulas. In light of this, the development of doctrine should be welcomed, not feared. Especially if it brings a little uncertainty.

Kyle Cupp is a freelance writer, contributor to Ordinary Times, and author of the book Living by Faith, Dwelling in Doubt (Loyola Press).

-

Metal-based compounds may be the future of antibiotics

Metal-based compounds may be the future of antibioticsUnder the radar Robots can help develop them

-

Europe’s apples are peppered with toxic pesticides

Europe’s apples are peppered with toxic pesticidesUnder the Radar Campaign groups say existing EU regulations don’t account for risk of ‘cocktail effect’

-

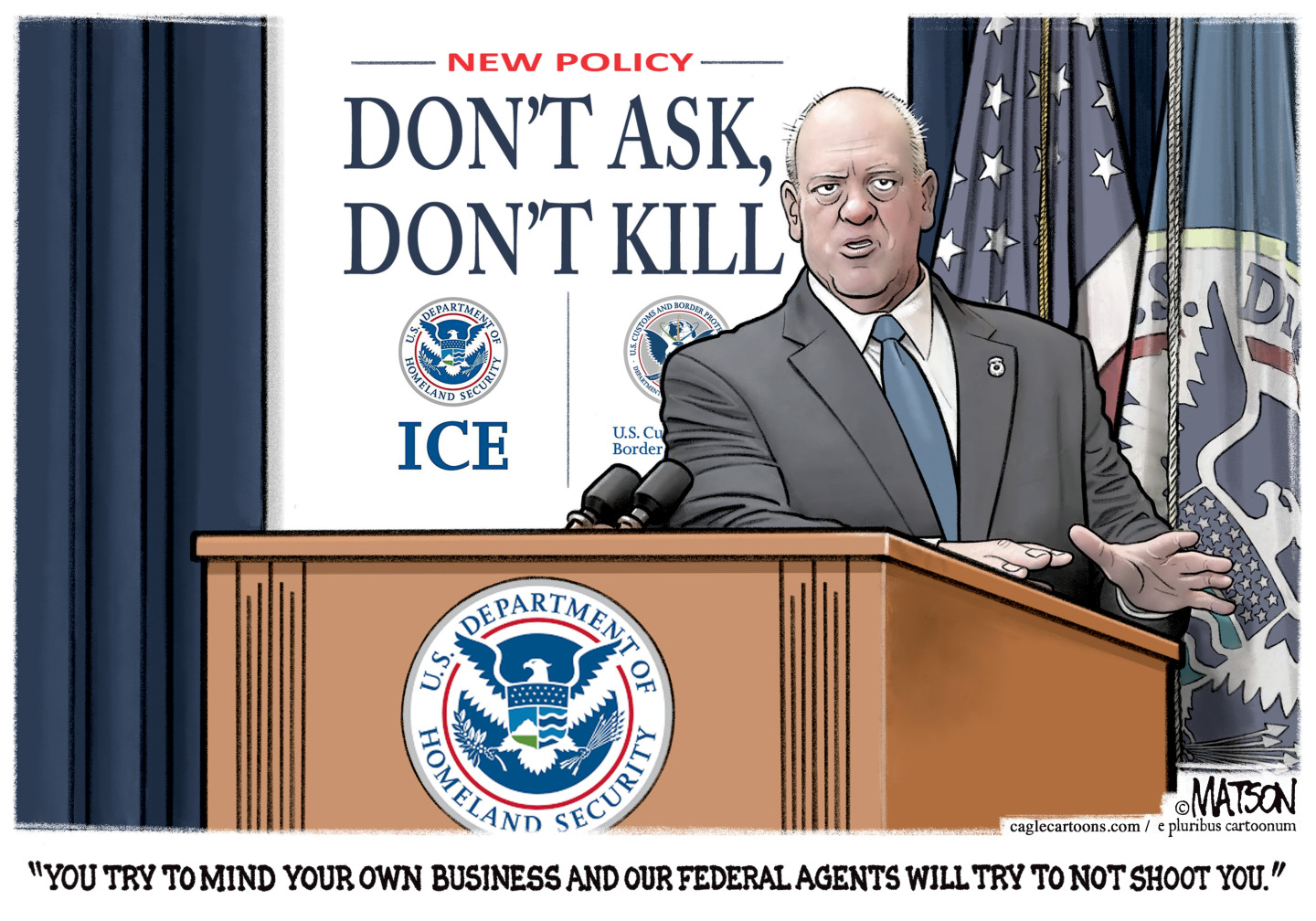

Political cartoons for February 1

Political cartoons for February 1Cartoons Sunday's political cartoons include Tom Homan's offer, the Fox News filter, and more