The lives of second-generation Holocaust survivors

As the last of those who lived through the Holocaust move into their late 80s and 90s, their descendants are stepping into the roles of torchbearers and educators

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

"I did not witness the most important events of my life," says artist David Gev. "They happened before I was born, yet their memory persists. How does one take on the memories of another individual, let alone the collective memory of millions?"

Gev, 53, lives in Los Angeles and has finally found a way to heal from a traumatic event he experienced long ago — some might say, in a different life. After a long career in international telecommunications commodities, he now has a new profession, that of artist. His medium is glass. Covered head to toe in protective clothing he fuses the scalding hot material and combines it with acrylic, aluminum, and wood. The final products are abstract "mixed-media sculptures," as he calls them — monochromatic linear panels made with rectangles of multi-colored glass arranged in rows. Each is titled "Journey," followed by a number. At first glance you would likely not link Gev's artwork to the Holocaust, but once you read his captions, the connection suddenly becomes clear.

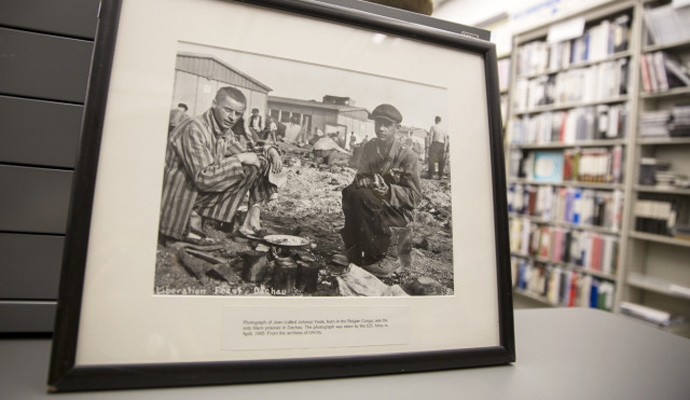

Gev was born in Be'er Sheva, Israel, in 1960. His father, Baruch Ginzberg, was a colonel in the Israeli Army, a post he took up after surviving four different concentration camps during the Holocaust. Ginzberg spoke little of his experience to David or his oldest son Israel in hopes of protecting them from the suffering he endured. In his artwork, Gev returns repeatedly to the view he imagines his father had through the slats in the cattle cars that transported him to Auschwitz-Birkenau, Sachsenhausen, Bergen-Belsen, and Dachau — each ride filled with fear, starvation, and death.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Gev did not directly experience this suffering, nor did he himself look out from the trains, or feel the pains of hunger and cold, but still he witnessed these things through pieces of stories told to him by his father. Without knowing all that occurred, he was forced to formulate images in his mind of what his father might have seen.

David Gev is what historians refer to as a second-generation Holocaust survivor. Hearing the stories and seeing their parents' anguish constitutes a traumatic experience for the children of survivors. As the last of those who lived through the Holocaust move into their late 80s and 90s, their descendants are stepping into the roles of torchbearers and educators. At the same time, the children are questioning if these are roles they can fill, wondering whether their voices can have the same impact the voices of actual survivors do.

(More from Narratively: Tobhi and Dan's imperfect proposal)

Elena Berkovits was only 16 years old when she first came face to face with Dr. Josef Mengele in the Nazi extermination camp at Auschwitz. Mengele, or the "White Angel," as inmates called him due to his white lab coat, was one of the medical personnel who would inspect people as they arrived. His motioning, left or right, would indicate if he deemed a person strong enough to work and therefore to live another day, or if they would be consigned to immediate death. In a brave act that nearly cost him his life, Elena's father broke from the men's line to tell her mother that Elena should lie and say she was 18 when questioned. He was severely beaten by soldiers for leaving his place in the queue, but his quick thinking saved Elena — she would later discover that most inmates 16 and under were sent to the gas chambers along with the elderly, as age was one of the principal criteria for selection. (After 1944, the age dropped to 14.)

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Berkovits has told her story hundreds of times to students at the Harriet and Kenneth Kupferberg Holocaust Resource Center and Archives (KHRCA), where she volunteers every Tuesday and where I serve as assistant director. Located on the campus of Queensborough Community College in Bayside, Queens, the Center is both museum and educational facility. Berkovits speaks to students all semester, but her voice cracks every time she recalls the moment her father risked his life for her. Students are enraptured by her telling, her bluntness, and the sense of humor that somehow peers through when she describes the unbelievable aspects of her survival. Berkovits enjoys speaking to them, and she cherishes the thank you letters and cards she has received over the years. On many occasions, students have lined up after class to personally thank her, and sometimes give her a hug.

But Berkovits has a new mission: She is working to document her experience during the Holocaust for another audience, her great-grandchildren. At 85, she has been able to watch her daughter and two grandsons grow into adulthood. While she visits with her great-grandchildren Avery and Foster at every opportunity, she is concerned that she won't get the chance to tell them about this time in her life when they are old enough to understand. She wants the story to be in her own words, so at the suggestion of her grandson, has begun working on a memoir for them. And not just one memoir, but two. Her first begins with the war and continues into the present; the second omits her experience of the Holocaust completely.

"I guess my grandson will read them the [abridged] story, and then when they are older they can read the full story themselves," says Berkovits.

(More from Narratively: Confessions of a suicide survivor)

After the liberation, Berkovits returned to Romania with her mother to look for family and friends who may have survived, and found very few. She was eager to restart her life in Romania, so she married in 1946, and three years later had a daughter. Berkovits came to the United States with her husband Izsak and daughter Vera in 1967. Vera was the only one of them who could speak English when they immigrated. She was 18 and immediately enrolled at Hunter College to study chemistry. Like her mother, she wanted to begin a new life in a new country and leave the past behind her.

Vera knew her mother lived through the Holocaust, but not of the details. "I never directly spoke about it until she was older," says Berkovits. "But she overheard things in the house when we were talking with our friends." In fact, Vera didn't learn the full story until she was a mother herself, and it wasn't by choice. Berkovits participated in filmmaker Steven Spielberg's interviews of over 52,000 survivors in the mid-1990s, which would develop into the Survivors of the Shoah Visual History Foundation. She was interviewed in her home; Vera and her two teenage sons were present.

"It was hard, I had to stop," Berkovits says. However, the Shoah Foundation interview was a turning point for her — it made her more comfortable sharing her experience.

Now that she is preparing her personal history for her great-grandchildren, what about the rest of the world? Will her daughter be able to testify to these events in her place? Berkovits thinks about it for a moment, her kind eyes looking into the distance. "Yes… No, probably not," she says. "It's hard for her to hear the story. When I am telling someone about it in front of her she says, 'Stop it mom.' She's very sensitive."

Not everyone will have access to Berkovits's memoirs, so if her daughter doesn't actively share her story, what will become of it?

The KHRCA holds bi-weekly meetings for Holocaust survivors called "Bagels and Talk." The executive director of the Center, Dr. Arthur Flug, explains: "I bring the bagels, they bring the talk." During the hour-long meetings, the group discusses everything from their lives in Europe before the war to the achievements of their grandchildren. David Widawsky, 65, a recently retired urban planner from Queens, brings his survivor father Sam to every meeting and sits in the back eating bagels and listening. One day he stopped in Dr. Flug's office and said that he wanted to volunteer. When Flug asked him what he wanted to do, he had no answer. A few weeks later he came to see Flug again and declared that he wanted to create a group like "Bagels and Talk," but for the second generation — the children of Holocaust survivors.

Widawsky describes the ensuing scene with a laugh: "Arthur jumped out of his chair and hugged me." Dr. Flug had always wanted to create a "2G" group but didn't have the time or resources to do so. They were easily able to compile a list of locals who were 2G. Widawsky gathered friends, Flug called survivors and put a notice in the KHRCA membership bulletin. Twenty names soon became 40.

When Widawsky began the group, he was thinking of the time when survivors will no longer be around to tell their own stories. "We have a responsibility to carry on the legacy, to be a transmitter of these stories," he says. The group's aim is two-fold: to train members to be tour guides at the KHRCA and integrate their personal experiences into the Center, and to prepare them to be speakers.

(More from Narratively: The shaman of Passaic)

Widwaswky recognizes that having the child of a survivor speak is not the same as having an actual Holocaust survivor speak. "People still want survivors, but later they will look to us," he says, describing the 2G as being "eyewitnesses to eyewitnesses." Widawsky feels that we can't rely solely on institutions and scholars to keep these experiences alive because they lack the personal connection.

Widawsky didn't learn his father's full story until he was in his twenties, although he knew he was a survivor. "I was always aware of it, I could feel it under my skin," he recalls. He says the Holocaust was barely mentioned in high school and college. It was as an adult that he went to a lecture at the CUNY Graduate Center and first grew interested in learning more about the Holocaust. It was then that he finally asked his father about his experience.

"He was waiting for the opportunity to talk about it," says Widawsky. "He started talking and he hasn't stopped."

Widawsky understands why his father didn't bring it up until he was asked. Talking with his peers in the 2G group, he has found that it is common for survivors to be reluctant to share these details with their children.

"No one knew when the right time to talk about it with their children was," says Widawsky. "It was like giving the sex talk — you know when they are definitely too young, but when?" There are many 2G who have never heard their parents' full stories and so will not have the opportunity to communicate them even if they would have liked to.

Read the rest of this story at Narratively.

Narratively is an online magazine devoted to original, in-depth and untold stories. Each week, Narratively explores a different theme and publishes just one story a day. It was one of TIME's 50 Best Websites of 2013.

-

Health insurance: Premiums soar as ACA subsidies end

Health insurance: Premiums soar as ACA subsidies endFeature 1.4 million people have dropped coverage

-

Anthropic: AI triggers the ‘SaaSpocalypse’

Anthropic: AI triggers the ‘SaaSpocalypse’Feature A grim reaper for software services?

-

NIH director Bhattacharya tapped as acting CDC head

NIH director Bhattacharya tapped as acting CDC headSpeed Read Jay Bhattacharya, a critic of the CDC’s Covid-19 response, will now lead the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention