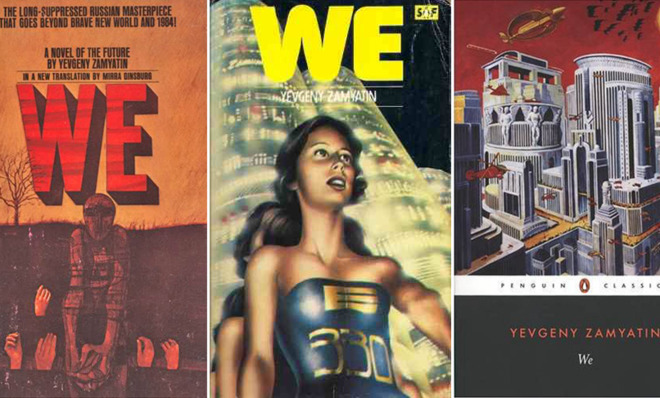

Yevgeny Zamyatin's We: A dystopian novel for the 21st century

We is a critique of a techno-socialist paradise — and it is more relevant today than ever

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The 20th century was haunted by literary visions of a future dystopia. In 1905, Robert Hugh Benson published Lord of the World, in which the Earth is governed by the Antichrist. Later dystopias would be more political: George Orwell's 1984 (1949) featured a cold, merciless, Party-dominated tyranny, while Aldous Huxley's Brave New World (1932) posited a drugged, manipulated, and productive society. The point of writing a dystopian novel is rather straightforward: for the best authors, it is a way of critiquing current trends and actors by drawing out their ideals and actions to their extreme conclusion.

I've loved all of the above, but the dystopian novel most relevant to our time is Yevgeny Zamyatin's We, which predated Orwell and Huxley, and obviously inspired the former.

Zamyatin wrote We within a few years of the Russian Revolution in 1917. The novel is set 1,000 years after a revolution that brought the One State into power. Citizens are known only by their number, and the story's protagonist is D-503, an engineer working on a spaceship that aims to bring the glorious principles of the Revolution to space. This world is ruled by the Benefactor, and presided over by the Guardians. They spy on citizens, who all live in apartments made of glass so that they can be perfectly observed. Trust in the system is absolute.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Equality is enforced, to the point of disfiguring the physically beautiful. Beauty — as well as its companion, art — are a kind of heresy in the One State, because "to be original means to distinguish yourself from others. It follows that to be original is to violate the principle of equality."

While 1984 and other dystopias featured surveillance and telescreens, We is the most analogous to the panoptical surveillance utopia being promoted by the tech gods of Silicon Valley, who seem to admire computers more than they do humans. In We, citizens see themselves as part of a glorious, infallible machine. In the One State, the Guardians and Benefactor urge men to live like machines themselves, so as to avoid even the possibility of failure. "One State Science cannot make a mistake," Zamyatin writes. He continues:

Why is the dance [of machinery] beautiful? Answer: because it is nonfree movement, because all the fundamental significance of the dance lies precisely in its aesthetic subjection, its ideal unfreedom. [We]

If men show any signs of rebellion, the part of their brain related to passion and creativity is removed through surgery.

Naturally, Zamyatin faced more harassment and punishment for his political views than any of his peers in dystopian literature, and he faced it in both pre- and post-revolutionary Russia. Born in 1884, his early forays into communism drove him into exile, though he returned to Russia during the 1905 Revolution that brought major liberal reforms to tsarist Russia. His involvement in that uprising saw him sent to Spalernaja Prison, where he endured solitary confinement.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Although he would go on to work for the regime's department of naval architecture, he wrote a fictional work, At the World's End, that was a satire of life in the military. He was acquitted in a trial over the book's seditious themes, but all copies of it were destroyed. Although he believed that war and famine could be overcome by collectivism, he soon became distressed at the Soviet Union's clampdown on the arts. He would later write in a series of samizdat essays, "True literature can only exist when it is created, not by diligent and reliable officials, but by madmen, hermits, heretics, dreamers, rebels, and skeptics."

We, a direct critique of socialist utopia, was smuggled into the United States, where it was published in 1924. After that, Zamyatin was hysterically condemned by the Union of Soviet Writers. Zamyatin resigned his membership, saying, "I find it impossible to belong to a literary organization which, even if only indirectly, takes a part in the persecution of a fellow member." Zamyatin's work was swiftly banned in the Soviet Union, and although he appealed directly to Stalin, Zamyatin was imprisoned until 1931, when Maxim Gorky intervened with the Soviet dictator and secured his release. Zamyatin moved to France, where he died six years later.

Zamyatin's exact political views are hard to define. He was horrified by the persecution he received at the hands of his fellow communists, but never settled definitively in a reactionary position either. His essays exhibit an almost mystical fascination with mathematics.

Revolution is everywhere, in everything. It is infinite. There is no final revolution, no final number. The social revolution is only one of an infinite number of numbers: the law of revolution is not a social law, but an immeasurably greater one. It is a cosmic, universal law — like the laws of the conservation of energy and of the dissipation of energy (entropy). Some day, an exact formula for the law of revolution will be established. And in this formula, nations, classes, stars — and books — will be expressed as numerical quantities.

One sees in the new maniacal hopes for "Big Data" a reflection of Zamyatin's tortured faith in the ability of mathematical investigation to reveal the mysteries of social life and history.

It is easy to see how his life as an artist — one whose work was condemned by two diametrically opposed regimes — encouraged a grim, fatalistic turn in his thinking. He wrote, "Today is doomed to die — because yesterday died, and because tomorrow will be born. Such is the wise and cruel law. Cruel, because it condemns to eternal dissatisfaction those who already today see the distant peaks of tomorrow; wise, because eternal dissatisfaction is the only pledge of eternal movement forward, eternal creation."

But Zamyatin made room in this fate for a spark of artistic revelation. He encouraged others to write "harmful literature" — literature that hurt the times in which it was published. "[H]armful literature is more useful than useful literature," he wrote, "for if is anti-entropic, it is a means of combating calcification, sclerosis, crust, moss, quiescence. It is Utopian, absurd — like Babeuf in 1797. It is right 150 years later."

We was finally published in Russia in 1988. It took only 64 years for Zamyatin to be right in his homeland — and he is right still.

Michael Brendan Dougherty is senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is the founder and editor of The Slurve, a newsletter about baseball. His work has appeared in The New York Times Magazine, ESPN Magazine, Slate and The American Conservative.

-

Switzerland could vote to cap its population

Switzerland could vote to cap its populationUnder the Radar Swiss People’s Party proposes referendum on radical anti-immigration measure to limit residents to 10 million

-

Political cartoons for February 15

Political cartoons for February 15Cartoons Sunday's political cartoons include political ventriloquism, Europe in the middle, and more

-

The broken water companies failing England and Wales

The broken water companies failing England and WalesExplainer With rising bills, deteriorating river health and a lack of investment, regulators face an uphill battle to stabilise the industry