Obama's stimulus succeeded — even if it was too small

Five years later, Republicans are still determined to portray the stimulus as a failure. Enough!

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

On February 17, 2009 — five years and a day ago — President Obama signed the American Reinvestment and Recovery Act, better known as the stimulus. The U.S. was going through the worst economic and financial crisis since the Great Depression. In the year leading up to the passage of the stimulus, private employers laid off 4.6 million workers. Trillions of dollars of household wealth had been wiped out due to the cratering stock market and plummeting real estate prices. The economy’s total output was in its most severe downturn in the post-war era. Clearly, something had to give.

The basic idea of economic stimulus spending is that if the private economy tumbles into recession — with falling economic activity and falling employment — then extra government spending on things like roads, bridges, schools, and energy can break the cycle of decline, and get the economy back to growth and robust employment. At the very least, the initial stimulus spending can replace activity lost due to cutbacks in private spending that occur in a recession. But by putting money in the pockets of previously unemployed workers and businesses, a stimulus can multiply up, boosting activity by far more than the initial investment.

One common (and foolish) objection to the idea of stimulus spending in a recession is that it will crowd out private spending. The British Chancellor of the Exchequer claimed during the Great Depression: "Any increase in government spending necessarily crowds out an equal amount of private spending or investment, and thus has no net impact on economic activity."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

In a downturn like the 2008 recession — with high unemployment and low and falling interest rates — this caution is clearly incorrect. When unemployment is high, it means there is slack in the labor market; workers who could be working are instead sitting idle. And when interest rates are low, it means there is slack in capital markets; investable capital is sitting idle. If the government was borrowing to stimulate the economy when unemployment wass low, and interest rates were high, then that could certainly crowd out private investment. But essentially, government stimulus spending in a depressed economy takes idle resources unemployed due to the market-panicking effects of the recession, and puts them back to work. This is a temporary measure, to tide the economy over until the animal spirits of the market make a comeback. And yes, sometimes government investment will channel money toward companies that fail (most famously, Solyndra); but occasional failure is the nature of investment.

Now: A new report from the White House's Council of Economic Advisers describes the stimulus as a pretty resounding success. The report claims that the stimulus saved or created about 1.6 million jobs a year for four years, through the end of 2012. The Recovery Act raised the level of real economic activity by between 2 and 3 percent from late 2009 through mid-2011. The cumulative boost to GDP from 2009 through 2012 is equivalent to 9.5 percent of fourth quarter 2008 GDP. And the report claims that the debt added by the stimulus may have been entirely offset by new economic activity.

These claims square pretty well with the estimates of other organizations, including the Congressional Budget Office. The stimulus did successfully put idle people and idle capital back to work. The real question, though, is whether it did enough of that. The unemployment rate only recently fell back below 7 percent. After the stimulus, the U.S. still had a rocky few years with very elevated unemployment and relatively weak growth.

This is something that opponents of the stimulus have seized upon. "Five years and hundreds of billions of dollars later, millions of families are still asking, 'Where are the jobs?' " House Speaker John Boehner said in a statement yesterday. He added that "a new normal of slow growth has set in.”

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Of course, we know that without the stimulus, unemployment would have risen by at least the amount of jobs created by the stimulus, and growth would have fallen by at least the amount of activity that the stimulus created. But the real world never experienced those effects. So opponents of stimulus can — with some superficial plausibility — claim that the stimulus "didn't work”, as the economy was still in the dumps for a long time.

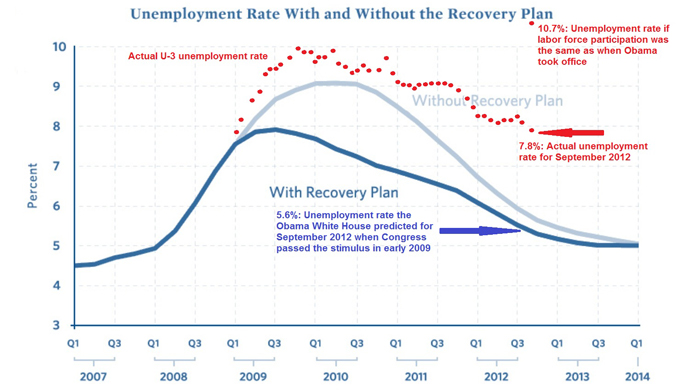

Furthermore, a prediction released by the Obama administration at the time of the stimulus estimated that unemployment with the stimulus would stay far lower than it actually did:

Clearly, the Obama administration underestimated the size of the slump, and by extension, sized the stimulus too low, certainly lower than many Keynesian economists wished.

In January 2009, Paul Krugman argued that the Obama stimulus was trying to plug a $2 trillion gap in the economy with a $775 billion stimulus. With such a small stimulus compared to the size of the recession, it is pretty unsurprising that unemployment has remained elevated while interest rates for government borrowing have remained extremely low (they’re at a similar level now to when the stimulus was passed). In other words, the stimulus just didn't eat up enough of the idle capital and labor to bring the economy back to full strength.

This problem could probably have been avoided if Congress and the Obama administration had taken a more open-ended approach to stimulus spending in the first place. For example: allocating an additional $300 billion per year of stimulus spending until either unemployment fell below 5.5 percent or interest rates on government borrowing rose above 5 percent.

But that approach has the advantage of hindsight. The key fact remains that at least the United States had substantial stimulus programs, unlike the Eurozone, which has tried to liquidate its way out of the slump with massive austerity programs, pushing unemployment in some countries such as Spain and Greece above 25 percent. This has allowed the United States much lower unemployment and much stronger growth than Europe.

Could the stimulus have done even more if it was bigger? Yes. Was there enough idle capital and labor to warrant a bigger stimulus? Yes. Were prominent economists warning the administration that the stimulus was too small before it went into effect? Yes. But in the context of the disaster that is the Eurozone, I think the U.S. government has earned the right to feel like it has done very well indeed.

John Aziz is the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also an associate editor at Pieria.co.uk. Previously his work has appeared on Business Insider, Zero Hedge, and Noahpinion.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day