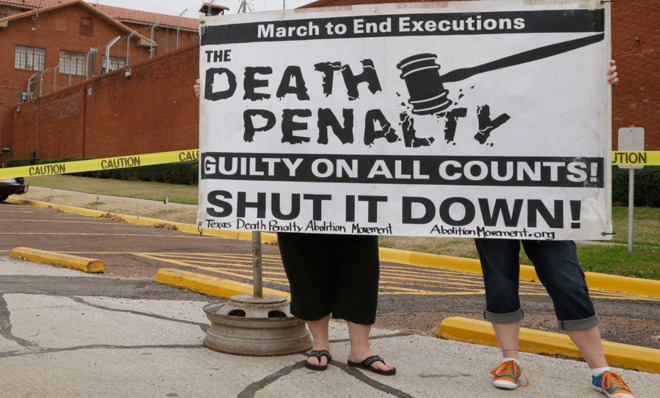

The slow death of capital punishment in America

Public support for the death penalty is plummeting, and executions are down by more than half from a decade ago

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

On Tuesday, Washington Gov. Jay Inslee (D) announced a moratorium on capital punishment in the state, saying that after months of deliberation, he had concluded the punishment was too fraught with legal and ethical qualms to be meted out any longer.

"There are too many flaws in this system today," he said. "There is too much at stake to accept an imperfect system."

Taken in isolation, the decision may seem relatively minor. Washington isn't ending the practice outright, nor is it commuting the sentences of prisoners already on death row.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Yet the moratorium is part of a much broader shift, both in policy and public opinion, away from capital punishment in the past two decades.

Last October, a Gallup survey found that 60 percent of Americans supported capital punishment. Though the raw number indicated strong support for the policy, it belied a sharp downward trend: it was the lowest level of support in four decades, and a marked drop from a record-high of 80 percent just two decades prior.

That shift coincided neatly with a downturn in public concern with crime. In 1992, nine in 10 Americans said there was more crime than the year before. In 2013, only two thirds said the same.

States have been slower to sour on the death penalty, but they, too, are now moving away from it. Eighteen states, including six in the last six years, have banned capital punishment. Several others, including California, have de facto moratoriums, meaning they haven't executed anyone in years even though there is no legal ban preventing them from doing so.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

As a result, states executed just 39 prisoners last year, a 60 percent drop from the record-high 98 executions in 1999, and only the second time in two decades the total number of executions has fallen below 40. Meanwhile, the number of death sentences nationwide has fallen by more than two thirds since the late 90s.

"The recurrent problems of the death penalty have made its application rare, isolated, and often delayed for decades," Richard Dieter, executive director of the Death Penalty Information Center, said last year. "More states will likely reconsider the wisdom of retaining this expensive and ineffectual practice."

A number of high-profile cases in recent years have shed more negative light on the practice.

In 2011, Georgia executed Troy Davis for the 1989 murder of a police officer, despite considerable doubt about Davis' guilt. Witnesses fingered a different shooter, others later recanted their testimony against Davis, and a closer examination of some evidence suggested it wasn't as strong as prosecutors originally claimed.

More recently, Ohio put to death a man, Dennis B. McGuire, in January using an untested drug cocktail. The procedure went awry. It took 25 minutes for McGuire to die, his last moments "accompanied by movement and gasping, snorting and choking sounds," according to The New York Times. The ordeal seemed patently torturous, and drew a rebuke from the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe, which deemed it "cruel and inhuman."

McGuire's execution underscored another problem holding back executions: a scarcity of lethal injection drugs. In 2011, Hospira Inc., the sole U.S. manufacturer of the execution drug sodium thiopental, announced it was ending production of the drug, citing pressure from anti–death penalty advocates. Subsequent attempts by states to import alternative drugs have gone nowhere, hamstrung by European regulations designed to stem overseas executions.

Some states, like Ohio, sought to skirt the shortfall by using other drugs. Wyoming considered a bill to reinstate firing squads, though the state Senate nixed the bill Tuesday.

Still, the very quest for alternative execution methods "only accentuates the absurdity of allowing the death penalty in a civilized society," wrote The New Yorker's Jeffrey Toobin. With the rate of executions plummeting, and with more squeamish states looking to ban the practice outright, the death penalty "now exists in a kind of twilight, a fading but still significant presence in American life," Toobin added.

Jon Terbush is an associate editor at TheWeek.com covering politics, sports, and other things he finds interesting. He has previously written for Talking Points Memo, Raw Story, and Business Insider.

-

How to Get to Heaven from Belfast: a ‘highly entertaining ride’

How to Get to Heaven from Belfast: a ‘highly entertaining ride’The Week Recommends Mystery-comedy from the creator of Derry Girls should be ‘your new binge-watch’

-

The 8 best TV shows of the 1960s

The 8 best TV shows of the 1960sThe standout shows of this decade take viewers from outer space to the Wild West

-

Microdramas are booming

Microdramas are boomingUnder the radar Scroll to watch a whole movie