The secret of the Ouija board

Spiritualists created the device, but businessmen made it a sensation

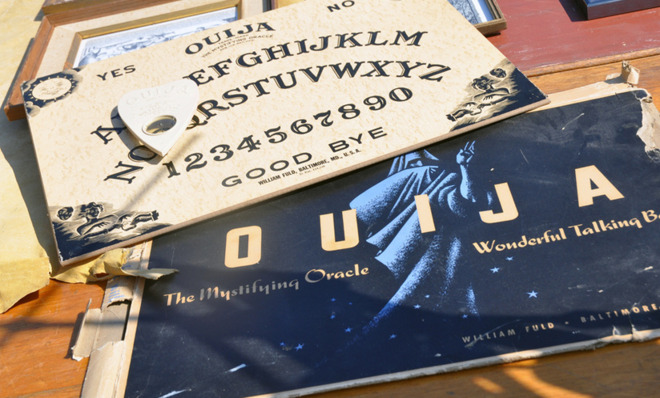

IN 1891, THE first ads started appearing in papers: "Ouija, the Wonderful Talking Board," boomed a Pittsburgh toy and novelty shop, describing a magical device that answered questions "about the past, present, and future with marvelous accuracy" and promised "never-failing amusement and recreation for all the classes," a link "between the known and unknown, the material and immaterial." Another ad declared it "interesting and mysterious" and testified, "as Proven at Patent Office before it was allowed. Price, $1.50."

This talking board was basically what's sold today: a flat board with the letters of the alphabet arrayed in two semicircles above the numbers 0 through 9; the words "yes" and "no" in the uppermost corners, "good bye" at the bottom; accompanied by a planchette, a teardrop-shaped device, usually with a small window in the body, used to maneuver about the board. The idea was that two or more people would sit around the board, place their finger tips on the planchette, pose a question, and watch, dumbfounded, as the planchette moved from letter to letter, spelling out the answers seemingly of its own accord.

Truth in advertising is hard to come by, but the Ouija board was "interesting and mysterious"; it actually had been "proven" to work at the Patent Office before its patent was allowed to proceed; and today, even psychologists believe that it may offer a link between the known and the unknown.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Ouija historian Robert Murch has been researching the story of the board since 1992; when he started his research, he says, no one really knew anything about its origins, which struck him as odd: "For such an iconic thing that strikes both fear and wonder in American culture, how can no one know where it came from?"

THE OUIJA BOARD, in fact, came straight out of the American 19th-century obsession with spiritualism, the belief that the dead are able to communicate with the living. Spiritualism, which had been around for years in Europe, hit America hard in 1848 with the sudden prominence of the Fox sisters of upstate New York; the Foxes claimed to receive messages from spirits who rapped on the walls in answer to questions, re-creating this feat of channeling in parlors across the state. Aided by the stories about the celebrity sisters and other spiritualists, spiritualism reached millions of adherents at its peak in the second half of the 19th century. Spiritualism worked for Americans: It was compatible with Christian dogma, meaning one could hold a séance on Saturday night and have no qualms about going to church the next day. It was an acceptable, even wholesome activity to contact spirits at séances, through automatic writing, or table-turning parties, in which participants would place their hands on a small table and watch it begin shake and rattle, while they all declared that they weren't moving it.

"Communicating with the dead was common, it wasn't seen as bizarre or weird," explains Murch. "It's hard to imagine that now, we look at that and think, 'Why are you opening the gates of hell?'"

But opening the gates of hell wasn't on anyone's mind when they started the Kennard Novelty Co., the first producers of the Ouija board; in fact, they were mostly looking to open Americans' wallets.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

As spiritualism had grown in American culture, so too did frustration with how long it took to get any meaningful message out of the spirits. Calling out the alphabet and waiting for a knock at the right letter, for example, was deeply boring. After all, rapid communication with breathing humans at far distances was a possibility — the telegraph had been around for decades — why shouldn't spirits be as easy to reach? People were desperate for methods of communication that would be quicker — and while several entrepreneurs realized that, it was the Kennard Novelty Co. that really nailed it.

In 1886, the fledgling Associated Press reported on a new phenomenon taking over the spiritualists' camps in Ohio, the talking board; it was, for all intents and purposes, a Ouija board, with letters, numbers, and a planchette-like device to point to them. The article went far and wide, but it was Charles Kennard of Baltimore who acted on it. In 1890, he pulled together a group of investors — including Elijah Bond, a local attorney, and Col. Washington Bowie, a surveyor — to start the Kennard Novelty Co. to exclusively make and market these new talking boards. None of the men were spiritualists, but they were all of them keen businessmen and they'd identified a niche.

BUT THEY DIDN'T have the Ouija board yet — the Kennard talking board lacked a name. Contrary to popular belief, "Ouija" is not a combination of the French for "yes," oui, and the German ja. Murch says, based on his research, it was Bond's sister-in-law, Helen Peters (who was, Bond said, a "strong medium"), who supplied the now instantly recognizable handle. Sitting around the table, they asked the board what they should call it; the name "Ouija" came through and, when they asked what that meant, the board replied, "Good luck." Eerie and cryptic — but for the fact that Peters acknowledged that she was wearing a locket bearing the picture of a woman, the name "Ouija" above her head. That's the story that emerged from the Ouija founders' letters; it's very possible that the woman in the locket was famous author and popular women's rights activist Ouida, whom Peters admired, and that "Ouija" was just a misreading of that.

According to Murch's interviews with the descendants of the Ouija founders and the original Ouija patent file itself, the story of the board's patent request was true: Knowing that if they couldn't prove that the board worked, they wouldn't get their patent, Bond brought the indispensable Peters to the patent office in Washington with him when he filed his application. There, the chief patent officer demanded a demonstration — if the board could accurately spell out his name, which was supposed to be unknown to Bond and Peters, he'd allow the patent application to proceed. They all sat down, communed with the spirits, and the planchette faithfully spelled out the patent officer's name. Whether it was mystical spirits or the fact that Bond, as a patent attorney, may have just known the man's name, well, that's unclear, Murch says. But on Feb. 10, 1891, a white-faced and visibly shaken patent officer awarded Bond a patent for his new "toy or game."

The first patent offers no explanation as to how the device works, just asserts that it does. That was part of a more or less conscious marketing effort. "These were very shrewd businessmen," notes Murch; the less they said about how the board worked, the more mysterious it seemed — and the more people wanted to buy it. "Ultimately, it was a moneymaker. They didn't care why people thought it worked."

And it was a moneymaker. By 1892, the Kennard Novelty Co. went from one factory in Baltimore to two in Baltimore, two in New York, two in Chicago, and one in London. And by 1893, William Fuld, who'd gotten in on the ground floor of the fledgling company as an employee and stockholder, was running the company. In 1898, with the blessing of Col. Bowie, one of only two remaining original investors, he licensed the exclusive rights to make the board. What followed were boom years for Fuld and frustration for some of the men who'd been in on the Ouija board from the beginning — public squabbling over who'd really invented it played out in the pages of The Baltimore Sun.

The board's prolonged success showed that it had tapped into a weird place in American culture. It was marketed as both mystical oracle and family entertainment, fun with an element of otherworldly excitement. This meant that it wasn't only spiritualists who bought the board; in fact, the people who disliked the Ouija board the most tended to be spirit mediums, as they'd just found their job as spiritual middleman cut out. The Ouija board appealed to people from across a wide spectrum of ages, professions, and education — mostly, Murch claims, because the Ouija board offered a fun way for people to believe in something. "People want to believe. The need to believe that something else is out there is powerful," he says. "This thing is one of those things that allows them to express that belief."

But the real question, the one everyone asks, is how do Ouija boards work?

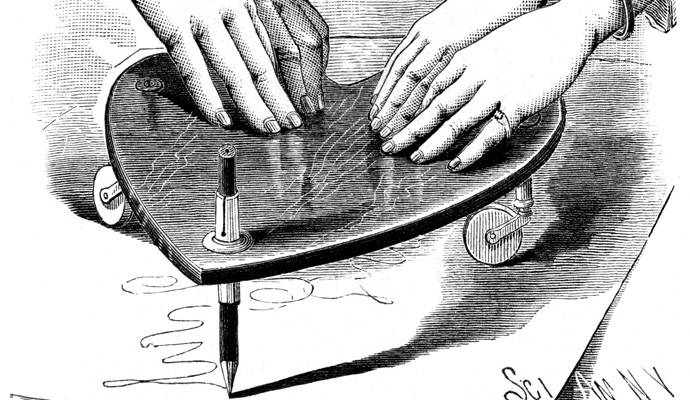

OUIJA BOARDS ARE not, scientists say, powered by spirits or even demons. Disappointing but also potentially useful — because they're powered by us, even when we protest that we're not doing it, we swear. Ouija boards work on a principle known to those studying the mind for more than 160 years: the ideomotor effect. In 1852, physician and physiologist William Benjamin Carpenter published a report on automatic muscular movements that take place without the conscious will or volition of the individual (think crying in reaction to a sad film, for example). Almost immediately, other researchers saw applications of the ideomotor effect in the popular spiritualist pastimes. In 1853, chemist and physicist Michael Faraday, intrigued by table-turning, conducted a series of experiments that proved to him (though not to most spiritualists) that the table's motion was due to the ideomotor actions of the participants.

The effect is very convincing. As Chris French, professor of psychology and anomalistic psychology, explains, "It can generate a very strong impression that the movement is being caused by some outside agency, but it's not." Other devices, such as dowsing rods, or more recently, the fake bomb-detection kits that deceived scores of international governments and armed services, work on the same principle of nonconscious movement. "The thing about all these mechanisms we're talking about, dowsing rods, Ouija boards, pendulums, these small tables, they're all devices whereby a quite a small muscular movement can cause quite a large effect," he says. Planchettes, in particular, are well-suited for their task — many used to be constructed of a lightweight wooden board and fitted with small casters to help them move more smoothly and freely; now, they're usually plastic and have felt feet, which also help them slide over the board easily.

"And with Ouija boards you've got the whole social context. It's usually a group of people, and everyone has a slight influence," French notes. With Ouija, not only does the individual give up some conscious control to participate — so it can't be me, people think — but also, in a group, no one person can take credit for the planchette's movements, making it seem like the answers must be coming from an otherworldly source. Moreover, in most situations, there is an expectation or suggestion that the board is somehow mystical or magical. "Once the idea has been implanted there, there's almost a readiness to happen."

©2013 Smithsonian Institution. Reprinted with permission from Smithsonian Enterprises. All rights reserved. Reproduction in any medium is strictly prohibited without permission from Smithsonian Institution.

-

Gabbard faces questions on vote raid, secret complaint

Gabbard faces questions on vote raid, secret complaintSpeed Read This comes as Trump has pushed Republicans to ‘take over’ voting

-

Which way will Trump go on Iran?

Which way will Trump go on Iran?Today’s Big Question Diplomatic talks set to be held in Turkey on Friday, but failure to reach an agreement could have ‘terrible’ global ramifications

-

High Court action over Cape Verde tourist deaths

High Court action over Cape Verde tourist deathsThe Explainer Holidaymakers sue TUI after gastric illness outbreaks linked to six British deaths