The best books we read in 2013

TheWeek.com's staff and writers discuss their favorite books of the year

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The Book of My Lives

When the inquisitive little alien on the cover of Aleksandar Hemon's The Book of My Lives caught my eye, I presumed this slim, 220-page book would be a light read. But I was badly mistaken, and perhaps my first clue should have been the fact that Hemon, a MacArthur-winning novelist, left his native Bosnia only two months before Sarajevo fell under siege in 1992.

But don't let that deter you: This isn't a misery memoir, either. Hemon, as the title implies, seems to have lived several lives, and each comes with its own mix of hardship and joy. His childhood in ethnically mixed Sarajevo was largely a happy one, filled with friends, family, and mischief. Life wasn't all peaches and cream in the former Yugoslavia, but since I suspect most Americans know little of what Bosnia was like before its descent into genocide, Hemon's loving portrait of its capital will prove eye-opening.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Throughout it all, Hemon smoothly toggles between humor and pathos. It's fun to see his wry observations about his adopted city of Chicago (where young affluent women "carry yoga mats on their backs like bazookas") develop into a full-blown urban crush. But in the final chapter, Hemon's snark completely evaporates. Small wonder: That chapter, "The Aquarium," recounts the illness and death of his nine-month-old daughter, a powerful story that alone is worth the price of admission.

The Book of My Lives is not an easy read; nor is it overbearingly mournful. Just something I'll carry with me for a long time. —Hallie Stiller, senior editor

The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay

Growing up is hard — especially when you don't have superpowers. Michael Chabon's fantastic, sprawling The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay tells the story of two cousins who break into the comic book industry during its heyday in the 1930s by combining their distinctive strengths: One's knack for writing pulp, and the other's keen artistry and fondness for depicting spandex-clad men socking Hitler in the face.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

With World War II constantly looming over the narrative arc — one of the cousins fled Nazi-occupied Prague, leaving behind his family — Chabon deftly weaves the real and the fantastical, the tragic and the comic, with superheroes serving as a backdrop for his protagonists' dreams, hardships, and triumphs. —Jon Terbush, staff writer

Blue is the Warmest Color

Though the controversial film version got most of the public's attention this year, it's Julie Maroh's original graphic novel, Blue is the Warmest Color, that really deserves the buzz. While the film adaptation framed women as a mythic construct men struggle to understand, the book revels in the opposite: A treatment of love that makes passion universal rather than particular or inexplicable.

In Maroh's story, Clementine posthumously sends her partner Emma to her family home to retrieve her journals. Facing grieving parents who don't understand Emma's place in their daughter's life, Emma reads through her late love's memories, which come alive in a room that hasn't changed since Clementine's sexual awakening as an adolescent. But sexuality isn't the subject so much as the entry point into something universal — the youthful struggle with tenuous friendships and intense feelings, and the fight to find one's place in the world. —Monika Bartyzel, "Girls on Film" columnist

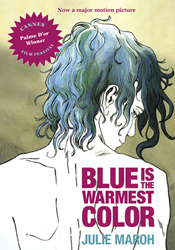

The Casual Vacancy

Responses to J.K. Rowling's The Casual Vacancy — the Harry Potter author's first foray into writing literature for adults — were mixed at best. Her second attempt, The Cuckoo's Calling, which was written under the pseudonym Robert Galbraith, went down much easier — although that was partly because initial reviewers could read it without the hype that attends every new Rowling book.

But The Casual Vacancy? You either loved this book or hated it. I fall into the first camp, and not just because Rowling is number two on my "favorite female authors of all time" list (Anna Quindlen will forever be number one). Many Potter fans despised Rowling's effort because it focuses on the more depressing side of life, with none of the wizarding world's magic and levity. Good. Many of us grew up with Harry, but The Casual Vacancy helps us navigate the tougher realities of the muggle world. If you want a rose-colored nostalgia-fest, re-read Rowling's YA classics. If you want to see her flex some deeper literary muscle, give this one a try. —Sarah Eberspacher, assistant photo editor

The Disaster Artist

I have a soft spot for a certain subset of movies that can charitably be called "so bad they're good" — and there's no movie that's more good-bad than The Room, a deeply bizarre melodrama that Entertainment Weekly has dubbed "the Citizen Kane of bad movies." The Disaster Artist, by Greg Sestero and Tom Bissell, offers a detailed and hilarious insider's look into the film's absurd production. The heart of this story is Tommy Wiseau, the writer/director/star of The Room who refuses to confirm his age or the source of his apparently limitless income (and has claimed, among other things, to be a vampire).

The Disaster Artist's co-author Sestero — who played Mark in the film, and also served as line producer — doesn't skimp on the juicy details. As it turns out, the film's production was just as rivetingly messy as the final product; Wiseau's tyrannical, freeform improvisation on set resulted in some of The Room's most memorable scenes (though his idea for a flying car did not, alas, make the final cut). As awful as The Room truly is, there's something strangely moving about Wiseau's quixotic quest for cinematic glory. And in a bizarre way, he accomplished his dream after all; The Room has left an indelible stamp on film history, and brought joy to thousands of viewers in the process. Isn't that every filmmaker's dream? —Scott Meslow, entertainment editor

Eleanor & Park

Rainbow Rowell's Eleanor & Park is a wonderfully told story about a pair of outsider teens who fall for each other after a slow-burn friendship. It's a book you'll stay up reading until dawn, dripping with tears and reminiscing over your first love. Eleanor, a lower-class teen with big, curly red hair, is an immediate target for teen venom. She ends up sitting on the bus next to Park, a half-Korean boy, whose punk rock–listening and comic book–reading make him an outsider in his sports-obsessed middle-class family. The two grow close, bonding over Park's comic books and making each other mixtapes. Their interactions are filled with the immediate, visceral details of high school crushes — brushed hands, passed notes, first kisses — that teem with electricity. Rowell splits the perspective between both characters, giving the reader a look inside their heads, which is where themes of race, family, and class also emerge. It's sweet, sad, and funny, and it makes you want to dance around your bedroom, listening to The Smiths while daydreaming about love. —Kerensa Cadenas, writer

Helter Skelter

As someone who has never read much true crime, I decided to go straight to the top and give Vincent Bugliosi's Helter Skelter a whirl. The story of Charles Manson's reign of terror in Los Angeles during the late 1960s is one you might think you know already — but after reading Bugliosi's book, you'll be floored by what you didn't. Helter Skelter is more than the story of the lead prosecutor in the trial against Manson; it's a time capsule capturing a fascinating era in Los Angeles and American culture writ large. It's hard to overstate how deeply the Tate and LaBianca murders rattled a population happily soaking in the remaining waves of free love and peace that the '60s had ushered in. It's a grisly, uncomfortable read (and one made especially creepy given the fact that I live mere blocks from one of the murder locations).

Helter Skelter is a story of the terror and fear that can be caused by even a small group of people. The book doesn't wrap up with a bow, instead opening up more questions about how the wayward can be led to make horrific choices. —Jessica Jardine, writer

Keynes: Return of the Master

Keynes is a difficult figure in the history of economics. Probably one reason for that is that there is so much misinformation about his ideas produced by people who have never really bothered to engage with them. In Keynes: Return of the Master, Lord Skidelsky successfully gets across Keynes' theories and their relevance to today's economy. Keynes thought that capitalism was not an end in itself, but should serve the goals of society and allow as many people as possible to live a good and fulfilling life. Markets — in other words, humans acting in large groups — work well most of the time, but sometimes they produce undesirable results like mass unemployment and economic depression. When markets fail to serve the needs of society, there is a necessity to correct the market failure. Perhaps more than anything else, that insight was Keynes' great legacy. —John Aziz, economics and business correspondent

My Struggle

There are many reasons for even the hardiest readers to be discouraged by the prospect of tackling Norwegian writer Karl Ove Knausgaard's autobiographical novel My Struggle. It is 3,500 pages long, comprising six hefty volumes. There is no traditional plot to speak of, with rambling passages of unadorned prose devoted to the most quotidian affairs, from playing "Smoke on the Water" in a high school cover band to enrolling his kids in daycare as an adult. And it ominously shares a title with the most notorious book to be published in the 20th century.

This would seemingly make Knausgaard an odd fit for the most exciting and talked-about writer to emerge on the global stage since W.G. Sebald. But spending even a few minutes with the first volume, available in translation from Archipelago Books, is to become absorbed to the point of distraction — prepare for missed stops on the subway and loved ones waving their hands to get your attention. Once you have made it through the second volume, it seems as if no book will quite suffice until Archipelago releases the third volume in 2014, leaving you with the choice of mentally drumming your fingers for another year or devouring previous books, interviews, and YouTube videos. I can't quite explain why this man's very ordinary life is so compelling, or more precisely how he makes the ordinary extraordinary; the birth of his first child, for example, reads like the first-ever recorded childbirth in human history. But in a way I suppose that makes perfect sense: Knausgaard, like all great writers, is some kind of magician. —Ryu Spaeth, deputy editor

Neverwhere

Neil Gaiman's Neverwhere is a master class in modern fantasy storytelling. The page-turner follows Scottish everyman Richard Mayhew as he accidentally — or perhaps fatefully — gets swept up in a hero's quest that takes him through a secret world beneath the streets of London called "London Below," which is filled with untold dangers and adventures. Richard is the unlikely companion to a young lady named "Door," whose family all have the special ability to open any door. (It's cooler than it sounds.) As he helps her on a mission to discover who murdered her family, Gaiman takes you through a terrifying, unfamiliar version of London, where Blackfriars tube stop is a monastery, a real angel resides at the Angel station, and the shepherds of Shepherds Bush are so dangerous that you should pray you never, ever meet them. It helps if you have some basic geographical knowledge of the city, but even without it, the fantastical tale is like the urban, adult version of The Wizard of Oz — and just as magical. —Jillian Rayfield, writer

Nineteen Eighty-Four

Although it's on hundreds of high school reading lists, I had never read George Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four until this year. Now I know what I was missing. Far beyond the cliches that have entered pop culture, Nineteen Eighty-Four delivers a potent punch in its presentation of a dystopian future in which people are constantly monitored, and the government attempts to control both its citizens and language itself.

Nineteen Eighty-Four is often referenced in contemporary political debate, and with good reason. Orwell's classic presents a haunting portrait of an all-powerful government. It is truly a book that came before its time and will remain in our collective consciousness in the years to come as surveillance (both public and private) continues to become more widespread. —John Hanlon, writer

Ready Player One

Ernest Cline's Ready Player One is nothing short of a 384-page geekasm: An unadulterated stream of pop culture references that includes everything from 80s sitcoms and old Atari games, to Dungeons & Dragons and DeLoreans — as well as the odd prog-rock allusion. The story, which is set in a future where a World of Warcraft-style virtual reality game has taken over society, follows a series of gamers as they embark on an epic scavenger hunt in a bid to unlock a world-changing secret that's worth billions of dollars. Engrossing, witty, and wildly inventive, it's a must-read for card-carrying geeks whose halcyon-tinged memories will be jogged with every turn of the page. A movie will inevitably follow (doesn't it always?). But it's worth tracking down the novel — or the Wil Wheaton-narrated audiobook — before Ready Player One is watered down for the big screen. —Daniel Bettridge, writer

Taipei

Tao Lin's Taipei is a weird, frustrating novel by a weird, frustrating writer — and I men that in the best possible way. At heart, the book is an unconventional romance centered on the characters Paul and Erin. Tao Lin has flirted with the literary establishment for years, but Taipei, his third novel, may be the first to bring Lin some semblance of mainstream acceptance and acclaim. There's a real wisdom that Lin brings to the table. It's a quick read at fewer than 250 pages, but Taipei also feels like a long book, with prose that is rigorously bereft of any liveliness. Instead the book is shrouded in a muted tone as Lin follows a small cast of twenty-somethings, who are washed out and adrift in New York and other East Coast cities. The aesthetic choice, while not always pleasant to read, has its own odd resonance that will stay with the reader long after the book is done. —John Hendel, writer

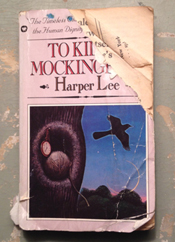

To Kill a Mockingbird

I picked up this mangled copy (at right) of Harper Lee's To Kill a Mockingbird while at my parents' house. I'm sure I was assigned this book as a student. Everyone was, right? And yet I could only vaguely remember the details — reclusive neighbor, a cumbersome ham costume — and I'm pretty sure that imagery comes from the film version. So I got to reading. And let me tell you: This Harper Lee is going places!

To Kill a Mockingbird is funny and sweet, a touch scary, and quite sad. It feels brave, considering the time in which it was written. And it's still, after more than 50 years, completely original — almost intimidatingly so. As someone who writes for a living and devours books in her spare time, I was taken aback by how well Lee drew these characters: The depth of Atticus' patience, Scout's endearingly insatiable curiosity, and Jem's heartbreaking realization that the world is a hypocritical place. When I mentioned to people that I was reading To Kill a Mockingbird, several reminded me that Lee never wrote another book after this one. My initial surprise at that somber fact faded with each turn of the page. How could anyone follow that up? Book publishing isn't struggling under the weight of new technology. It's that the industry peaked in 1960. —Lauren Hansen, multimedia editor

We Learn Nothing

After spending the greater part of the year slogging through George R.R. Martin's snoozefest A Feast For Crows, I started reading Tim Kreider's collection of essays, We Learn Nothing, not knowing what to expect. (One of them, "The 'Busy' Trap," was excerpted in The Times.) Kreider has made a career as a liberal political cartoonist, and he proves here to be a hilarious and deft essayist who possesses a deep appreciation for other people and all their awful complexity. It's a fun, thoughtful read, and the most memorable book I picked up this year. His chapter on attending a Tea Party rally will inject rainbows and sunbeams into even the iciest of hearts. —Chris Gayomali, science and technology editor

Wonder

There are certain books that make you a better person simply by having read them, and R.J. Palacio's debut novel, Wonder, is one of them. Though it's been touted as a children's novel, in many ways adults have far more to gain from the poignant tale of Auggie Pullman, a 10-year-old boy who suffers from a rare facial anomaly that has caused adults and children to recoil in horror at the sight of him since birth.

Wonder begins with Auggie transitioning from homeschooling to a public education for the first time, using our protagonist's perspective alongside five other young narrators to weave a tale at turns both gut-wrenching and uplifting. As many of us have encountered bullying at one time or another, Wonder has much to teach us about grace, courage, and the ripple effect that can result from a simple act of kindness. —Laura Prudom, writer

You Don't Know Me But You Don't Like Me

I picked up Nathan Rabin's You Don't Know Me But You Don't Like Me expecting a skewering of two of music's most hated groups: Rap group Insane Clown Posse and the jam band Phish. Instead, I got a memoir of several of Rabin's love affairs — with his wife in the time before their marriage, with the twisted but inviting mythology of Insane Clown Posse, and with the collective ecstasy of the lot outside a Phish show.

In the course of his investigation, Rabin beautifully communicates the sense of belonging and community that draws societal outsiders — but also poets, bankers, over-educated junkies, and everyone in between — to Phish and ICP. It's truly impressive that You Don't Know Me renders two of American culture's broadest targets for ridicule as eminently sympathetic and even inviting. I'm not sure I'm ready to head to the Gathering Of The Juggalos, but I'll definitely be seeing Phish the next time they're in town — with my copy of the book in tow. —Eric Thurm, writer