The lingering mystery of the 1964 World's Fair

A subterranean mystery has baffled history buffs from Flushing to Florida

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

A mid-afternoon rainfall has saturated the dirt just enough that Dr. Lori Walters easily unearths some with the tip of her black loafer. A few yards away, groups of Latino men in bright t-shirts and blue jeans are playing a casual game of volleyball, bumping but never spiking, on a lazy Sunday in Flushing Meadows-Corona Park, the largest park in Queens.

Dr. Walters is tired. She has been on her feet for much of the past two days, running an exhibit at a science fair teeming with children and parents. Her fingers brush back strands of brown hair that a gentle wind has blown out of place, and she tucks her hands into the large pockets of a maroon jacket. Her slender body is weary, her voice cracking, and she still has a long trek home to Florida, where she is a history professor.

A wayward volleyball — actually an old soccer ball, which serves the same purpose — hits the hard ground with a thud. Greenery envelops most of Flushing Meadows-Corona Park, but not here, where patches of brown grass sprout between large swaths of exposed dirt. Saplings never seem to stand a chance.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

(More from Narratively: The food fluffers)

Surely, trampling takes a toll on the turf. But can that be enough to stop the growth of trees? Might something be down there, obstructing their existence?

Dr. Walters perks up.

"It's a mystery," she says, beaming. "Is it there? What does it look like?"

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

She grows eager and smiles, wondering if something, anything, remains at this spot from nearly half a century ago, when it was transformed into Block 50, Lot 5, at the 1964 World's Fair.

"We could probably figure out something at this moment if we wanted to just dig."

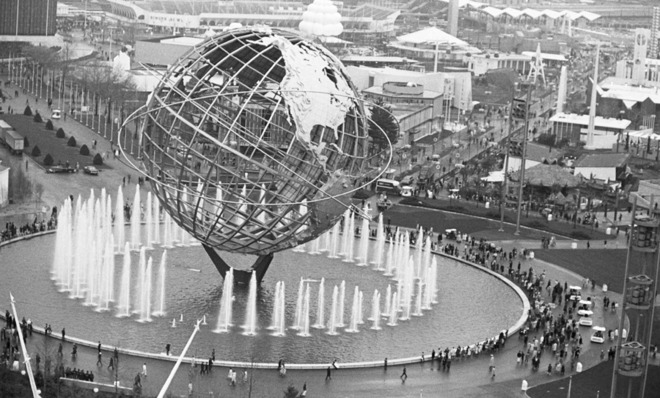

Size mattered at the World's Fair — especially height. Spread across nearly a square mile of Queens were hundreds of exhibits from states, countries and corporations that equated altitude with esteem. The Unisphere, a stainless steel globe that came to symbolize the fair, towered twelve stories tall. Elevators dubbed Sky Streaks whisked passengers 226 feet to the observation deck of the hulking New York State Pavilion. Other attractions had spires or high-pitched roofs.

But not at Block 50, Lot 5.

"Most of the architectural highlights of the World's Fair spiral skyward," the New York World-Telegram & Sun reported on November 18, 1963. "And then there's the Underground World Home."

* * *

Coinciding with the 300th anniversary of New York City, the 1964 World's Fair offered an awe-inspiring array of whimsical rides, displays of state-of-the-art technology, and glimpses of exotic cultures. Many of the 140 pavilions looked to the future, imagining radical, wondrous changes in the life of the average American. Organizers slated the fair to run for two six-month seasons, from April to October in 1964 and '65.

In the lead-up to the fair, the New York press marveled at the newly constructed subterranean dwelling that most knew simply as the Underground Home. The Wall Street Journal welcomed "a new frontier for family living." The Herald Tribune extolled the virtues of living with "good old earth on all sides." By the time the fair opened on April 22, 1964, the Underground Home had already generated headlines in all the major dailies.

(More from Narratively: How Wall Street traders are impacting global hunger)

Jay Swayze was delighted. A lumber dealer and home builder from Plainview, Texas, Swayze designed the Underground Home in the aftermath of the Cuban Missile Crisis, when many Americans feared an impending nuclear attack. Families hurried to build fallout shelters, but many of them were bland and cramped. Swayze began tinkering with spacious underground homes suitable for year-round living.

Protection from radioactive fallout, as well as everyday noise and pollution, lured a bold-faced name to Swayze's work. In 1964, Girard Henderson, who sat on the board of directors of Avon Products, the beauty manufacturer, had an underground residence built for him in Colorado. He was so enthralled that he financed Swayze's Underground Home at the World's Fair, convinced that the masses would buy into subsurface living, too.

Swayze's team scored a plot on the fairgrounds between the Hall of Science and the Port Authority Heliport, and they began to dig fifteen feet into the Flushing Meadows marsh. Within a few months they had created a concrete shell of about 12,000 square feet and installed the home's gypsum board ceilings. Candelabras sat on the Steinway & Sons piano in the living room. A simulated garden featured a bed of plastic flowers, artificial wisteria, and an organ.

Like other exhibits at the fair, the Underground Home incorporated many novel accoutrements. A snorkel-like system pumped air into the ten-room house. The lighting allowed residents to pick the time of day and the season they wanted with just the turn of a knob — like "midnight at noon" and "summer in winter," as Swayze bragged. He also installed "dial-a-view," which let occupants pick the murals they would see through the windows. One of the choices was a knight riding a horse to a castle.

The Underground Home was billed as "sub-urban," in keeping with the clever marketing that permeated the fair. But it was not like other exhibits. A glance at a bookshelf inside the home underscored the chief motivation for buying such a dwelling. One book was titled "Our New Life with the Atom." Another was "Foreign Policy Without Fear."

The Miami News ran a telling caption with its profile of the home's interior designer, Marilynn Motto: "Her designs are enough to calm a subterranean dweller during an H-bombing."

These reminders of a nuclear age seemed out of place at a fair with so many bright visions of "the world of tomorrow today." The fair embraced a theme of "peace through understanding," while the Underground Home was most appealing to visitors who didn't think peace would last very long.

"The idea of an underground home in '61 or '62 was to protect you from the Soviets — the evil, nasty Soviets," Dr. Walters says. "Along comes the Cuban Missile Crisis, and you realize we can blow ourselves off the planet."

Swayze deemed his exhibit a success. Fifteen years after the fair ended, he published a book on underground living that described a parade of visitors roaming the Underground Home, all of them declaring, "This is a dream world." He boasted that more than 1.6 million people had visited the home, a stunning total.

By most other accounts, the Underground Home was a flop. At a fair where many popular exhibits were free, it had an admission price of a dollar for adults and fifty cents for children. Some doubt that the home enjoyed so many visitors when other, more thrilling, attractions charged nothing at all. General Motors had set up a free ride called Futurama, where passengers witnessed scenes of a jungle, the moon, and a futuristic city that had moving sidewalks and midtown airports. Walt Disney designed the equally impressive, and equally gratis, Magic Skyway ride at the Ford Pavilion.

Swayze's bottom line may have also been hurt by the lack of souvenirs he sold. Only two were available at the Underground Home: an eight-page brochure on underground living, few of which survive today because few were probably bought, and an LP record by Grammy Award-winning singer Johnny Mann, a friend of Henderson, the underground home aficionado and Avon board member.

(More from Narratively: Tense times in graffiti town)

Also sold, of course, were the homes themselves, at the hefty price of $80,000 each, more than half a million dollars by today's standards. But visitors, it turned out, were unwilling to radically alter their lifestyles and plunk down so much money on what amounted to an experiment. Near the end of the fair's first season, The New York Times reported that not a single underground home had been sold.

After the fair ended in the fall of '65, most of its attractions were demolished so the city could transform the sprawling space into what would become the 1,250-acre Flushing Meadows-Corona Park. Only a few structures evaded the wrecking ball, and most of them remain today, including the Unisphere, the New York State Pavilion, the Hall of Science (later re-branded as the New York Hall of Science), and the Port Authority Heliport (now a catering hall dubbed Terrace on the Park). The rest had to be torn down by the exhibitors, as mandated by their contracts.

Some, however, believe that Swayze, wanting to avoid high demolition costs, removed furnishings from the Underground Home but left its shell intact, hidden beneath several feet of dirt.

"I doubt that Mr. Swayze did more than he had to," says Bill Cotter, who has written several books on world's fairs.

Cotter visited the Underground Home on one of many adolescent treks from Long Island to the fair, as part of a personal pledge to see every exhibit at least once. Now 60, he helps run a message board known as the World's Fair Community, where Baby Boomers who attended the fair have united to reminisce. Many of them had never before been exposed to such culture and technology, so they rank their visits to the expo among the most memorable experiences of their lives. They recall eye-opening demonstrations of computers and picture phones. They remember waiting in long lines at the Vatican Pavilion to glimpse Michelangelo's Pietà, walking through the Sinclair Oil exhibit to check out the moving dinosaur figures, and visiting the Belgium Village for a taste of a delicacy that would become known as a Belgian waffle.

One of the most popular topics on the message board is what became of the Underground Home. Lively discussions on the site have revealed two prevailing views: Some think that parts of the Underground Home may still exist, while others doubt Swayze left anything behind.

It's clear where Cotter stands: "If you had a chance to just cover it with dirt and run like hell, or spend money to rip things out, which of the two options would you take?"

Read the rest of this story at Narratively.

Narratively is an online magazine devoted to original, in-depth and untold stories. Each week, Narratively explores a different theme and publishes just one story a day. It was one of TIME's 50 Best Websites of 2013.

-

5 cinematic cartoons about Bezos betting big on 'Melania'

5 cinematic cartoons about Bezos betting big on 'Melania'Cartoons Artists take on a girlboss, a fetching newspaper, and more

-

The fall of the generals: China’s military purge

The fall of the generals: China’s military purgeIn the Spotlight Xi Jinping’s extraordinary removal of senior general proves that no-one is safe from anti-corruption drive that has investigated millions

-

Why the Gorton and Denton by-election is a ‘Frankenstein’s monster’

Why the Gorton and Denton by-election is a ‘Frankenstein’s monster’Talking Point Reform and the Greens have the Labour seat in their sights, but the constituency’s complex demographics make messaging tricky