The evolutionary roots of Mean Girls

Cattiness, bitchiness, and gossiping may serve an evolutionary purpose among women. But does it have to be the norm?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

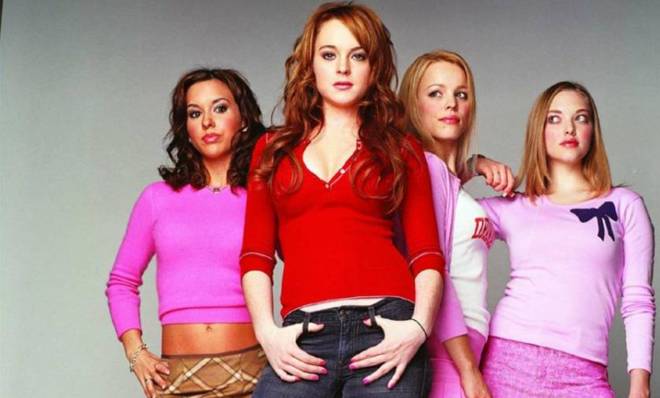

It turns out the cunning, gossiping, and slut-shaming ways of Regina George may be rooted in thousands of years of evolution.

Some scientists are claiming that adolescent women who express the intra-female competition so keenly documented in Rosalind Wiseman’s Queen Bees and Wannabees and Mean Girls come by it honestly. Or at least evolutionarily.

Tracy Vaillancourt argues in the journal Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B that women have evolved to express indirect aggression — as opposed to outright violence — to ward off female competitors.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Working with researcher Aanchal Sharma, the two studied how women display greater indirect aggression towards attractive women in revealing clothes than women dressed conservatively (because we haven’t noticed this all in a high school cafeteria). They secretly videotaped college women having an ostensible conversation about friendship, who were then interrupted by a woman who met all the traditional standards of beauty from a modern and evolutionary perspective: Low waist-to-hip ratio, clear complexion, and, of course, large breasts.

When the woman was dressed in pants and a t-shirt, she was barely noticed. When she interrupted in a short skirt and revealing top, the responses were catty, to say the least.

Vaillancourt and Sharma used a scale of “bitchiness” to measure the reactions, which included eye-rolling, staring the potential competitor up and down, and mocking her once she left the room, notes Olga Khazan at The Atlantic.

Women were also significantly less likely to say they would introduce the scantily dressed vixen to their boyfriends than the conservatively dressed one. One girl went so far as to say the less modestly dressed confederate was probably trying to sleep with a professor.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

These reactions are neither happenstance nor (at least solely) a response to modern pressures to sexually and physically conform to a certain standard. And while men perpetuate these pressures, they are not the main drive behind them, according to Vallaincourt. Instead, she tells the New York Times, “The research shows that suppression of female sexuality is by women, not necessarily by men.”

“Sex is coveted by men,” Vallaincourt explains, and therefore is a source of female power in relationships. “Women who make sex too readily available compromise the power-holding position of the group, which is why many women are particularly intolerant of women who are, or seem to be, promiscuous.”

Attacks on physical appearance, especially weight, could also fall under Vallaincourt’s thesis, since such attacks could leave victims “too sad and anxious to compete in the sexual market,” says Tia Ghose at LiveScience.

But is it fair to chalk up all the catty behavior to evolution, and give mean girls a free pass? Obviously not, and there is plenty to question about how enduring a role evolution plays in this internecine female warfare.

Kim Wallen of Emory University tells LiveScience that none of the studies citied in Vallaincourt’s report, including her own, “contain data showing indirect aggression is successful in devaluing a competitor.” If a tactic hasn’t been successful in knocking out competition, then there’s no clear reason why it would be a behavior passed down as an adaptive skill.

Moreover, while this study and other similar ones are quick to place the blame for “bitchiness” primarily on women, they glaze over the role that men and the media play.

For example, Christopher J. Ferguson of Stetson University tells the New York Times of a study showing women who watched a TV show with skinny female characters felt no worse about themselves than those who watched a show with heavier female characters. But both groups of women felt worse when they were in real-life social situations with thinner women, thus proving, says Ferguson, that it was other women, not the television shows, that made them feel bad. “To a large degree the media reflects trends that are going on in society, not creates them,” he says.

But maybe these women feel worse in real life around skinnier women because they see in television shows, movies, and advertisements that thinner women have greater success with men or are generally more valued. Media images may still be responsible for the catty behavior, and they certainly deserve blame for reinforcing it.

And because men keep valuing the traits that women compete over, namely attractiveness and sexual fidelity, they, too, reinforce behavior. In fact, the ball may be in their court. University of Texas psychologist David Buss tells The Atlantic, “The only way it [intra-female competitive behavior] might change is if men stopped valuing sexual fidelity and physical attractiveness in long-term mates.”

Since that’s probably not happening anytime soon, maybe the best thing to do is to make a new generation of female adolescents watch Mean Girls on repeat, so they know how that whole Regina George routine works out. It might improve the situation faster than waiting on evolution.

Emily Shire is chief researcher for The Week magazine. She has written about pop culture, religion, and women and gender issues at publications including Slate, The Forward, and Jewcy.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day