Blood, honor, and partition: A survivor's tale

"What I saw held me spellbound. Each by turn, one by one, all the women were lining up to get beheaded. They wanted to die!"

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In 1947, as the old British Indian Empire was breaking up, violence between Muslims, Hindus, and Sikhs erupted in parts of what would become Pakistan and India. In the small town of Thao Kalsa, Sikh landlords, surrounded and outnumbered, made a grim decision. A young boy witnessed the result.

***

Last winter, after lecturing at a nearby university, I traveled to Delhi to interview an eyewitness to the gory events of 1947 in the old British Indian Empire. He is an old man now, eighty-two. He sat in the spacious and well-lit lobby of his house, remembering what he saw when he was 16 years old in Thao Khalsa, a peaceful village in the northern part of what would become Pakistan.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

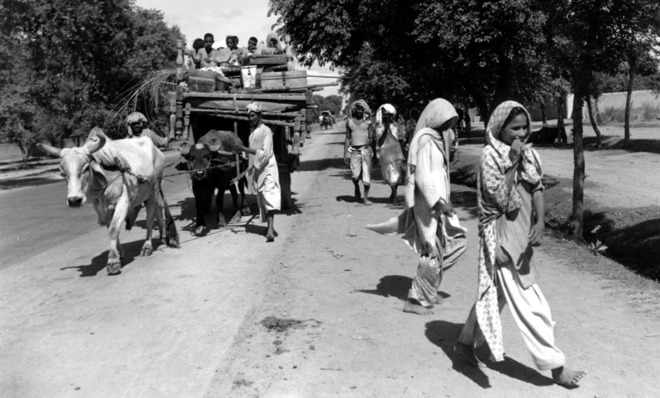

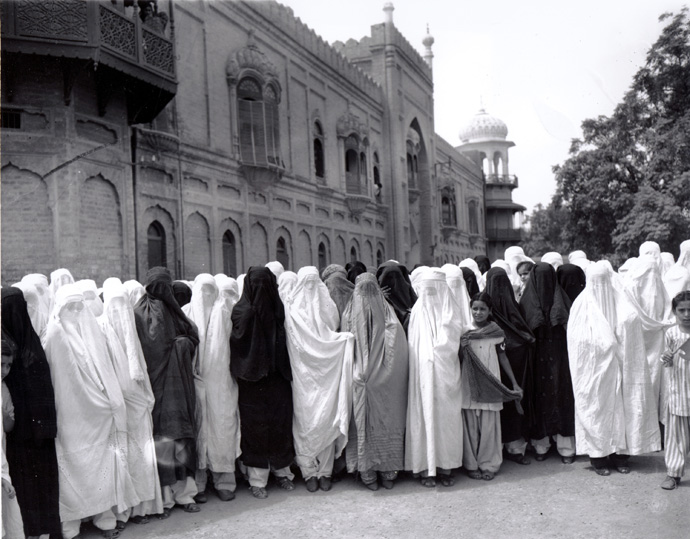

In those years the Indian independence movement was at its peak, as was tension between Hindus, Muslims, and other groups, each fearing domination. Such conditions eventually led to the Partition, which essentially divided the empire into two nations, India and Pakistan. It was a blood-soaked period: around half a million people were killed and some 14 million were displaced, crossing borders in search of a safer place on grounds of religion.

At the time, Thao Khalsa was inhabited by Hindus and Sikhs. They owned the land and made a living by farming. Muslims from adjoining areas worked as their laborers. On March 6, 1947, seemingly out of the blue, Muslims attacked the Sikhs. Our eyewitness, who wishes to keep his name unpublished, endured a terrible ordeal. His emotions ran high as he spoke about it, and I did not interrupt. This is his story.

***

They came to our village by the hundreds and thousands, all equipped with swords, knives, and sticks. In minutes, Thao Khalsa was surrounded. It was a harsh night: March 6, 1947.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Ours was a little village of a few hundred families, mostly zamindars (landlords), both Hindus and Sikhs. The attackers were mostly the laborers in our own farms. I still don't remember — What was the cause? Why did they attack us? Sixty-six years makes it hard to recount.

We fought for three days. No, not me — I was just 16. I was locked upstairs in my haveli [mansion] with my sister and with my mom and several other women of our house. Some other children were also with us. A small window on the left wall was the only way to observe what was happening outside.

(More from The Big Roundtable: The man that wasn't)

The clashes were turning bloody — a few hundred people against an uncountable armed mob. The possibility of getting out alive looked thin. My father was fighting, blazing red in anger, and the bloodstains on his dress made him look even more furious. His khanda (adouble-sided sword) was piercing the bodies of those Muslims. Blood was pouring in all directions. There were several other leaders fighting shoulder to shoulder by his side.

The attackers had the benefit of number: One would fall and another would take his place. The number of villagers fighting was gradually dwindling over time. After three days of furious battle, the leaders of the village decided to negotiate a truce with the attackers. They were concerned for the lives of the villagers. In return for sparing the village, the the attackers had a demand: They wanted custody of one of its girls.

That girl, a Hindu, was very beautiful, with a proportionate body and long hair that reached down her back. She had a relationship of sorts with one of the Muslim boys. The village was well aware of it. Her parents also knew about the relationship. The village leaders, at first, contemplated agreeing to this demand.

But the thought was later dismissed. My father refused it. We were Sikhs and couldn't let that happen. Trading a girl for life with Muslims was worse than death for a Sardar [a term of nobility]. Protecting the womenfolk was a virtue that had been established by our Gurus, who sacrificed a lot of blood fighting rulers of the like of Aurangzeb [a Mughal ruler of the seventeenth century].

My father devised a way to put the voices of dissent to rest, and to set a precedent.

***

I had been hungry for three days. It was not only me, but all the others locked up with me in that little room: hungry and frustrated. Every face had a weird expression, having witnessed the bloodshed from our only window and having thought all sorts of things. Questions crowded our minds: How many are dead? Is the battle over? When will we get out of this room? Will we live?

***

On March 9, we were finally allowed to walk down the stairs and into the common hall. There were some other women there. My father and his brother, along with several other villagers, were also present. His cloak was red with blood. He was also bleeding — not profusely, but I thought that if it was allowed to continue he would die of blood loss.

What my father did next was most unexpected. He and his brother, my uncle, rounded up 26 women of the house in the common hall of the haveli. I was again asked to go upstairs along with my mom and all the little children. The young women, from age 15 to 45, were kept in the hall. My curiosity made me go downstairs again. All the women were now sitting in the middle of the room. I tried to hide behind the staircase, but my father looked at me. He told me to come and sit along with the other people.

My uncle said, "He is too tender for this."

"He is a Sikh," my father replied.

I stayed.

It was not clear what was going on. Some of the women looked horrified; some looked proud. I didn't know what was going on in their minds.

My father walked to the middle of the room. His khanda was stained with blood.

He called out in a loud voice to my sister, "ither aa" (come here). My sister stood up. She walked down to him and bowed her head. Her duppata (scarf) was on her neck. Her long hair was tied in a guth. They lifted her duppata off her bare neck. It was in my father's way. He put his hand on her head. She stood up and then shifted her hair to the front.

I was still confused about why she had bared her head in front of all the people — for Sikhs, uncovering the head is considered disrespectful. She again bowed. My father lifted his khanda and cried Waheguru! (Almighty Lord!).

What I saw the next moment was most horrifying. My sister's head fell. Her body fell on one side and her head on other. Fountains of blood colored the floor. My father's face was all blood. So were his clothes.

(More from The Big Roundtable: The girl who wouldn't die)

I fainted. I was in shock. How can a father behead his daughter? How can all those people be spectators? How can a girl come to get slaughtered? How can her face portray pride in death? How? How? Tears were rolling down from my eyes. All these questions flashed in my mind. I was lying down, nearly comatose. The moment I woke up, I saw that I was soaked in blood. My sister's blood had reached me.

***

My uncle came to my side and said, 'You are a Sikh: Look there.' I was still dizzy. I managed to look at that side of the room again.

What I saw held me spellbound. Each by turn, one by one, all the women were lining up to get beheaded. They wanted to die! The blood that had reached my feet was now not only the blood of my sister, but of three more bodies that were lying on the floor. All beheaded! There were 26 women in total. This continued till the last one.

Now the room was flooded with blood. At last he again cried 'Waheguru!' and then shouted the victory cry, 'Bole So Nihal, Sat Sri Akal.' Every single person in the room replied to it. The room echoed.

Only then could I fully take in the surrounding. A mob in a trance; the bodies piling on each other, their heads oozing blood; the red floor, ankle-deep in gore; and a man in the middle with a khanda in his hand and satisfaction on his face. Everything was in a single frame. I could see it all — still, majestic, spellbinding. I adjusted my head to take in more of the scene.

There was an unfamiliar silence in the hall. Everyone was looking at my father, including me. I was still unable to understand why he had gone on this rampage, killing all the women. Was it a rampage? He looked calm and proud. Why did he kill them? Why didn't any one object? Why was no one crying? Why this unusual expression of satisfaction on everyone's face? What wrong had the women done? Why had they all gone forward, smiling, to get beheaded?

I didn't have any answers. Nor could I ask my father. Disgust was engulfing me.

(More from The Big Roundtable: My rehab: Coming of age in purgatory)

The older women and the children were locked upstairs. Were they unaware of what had happened down here? Their aunts, moms, sisters killed? The noise of blades clashing against each other again came from outside the hall. A few villagers rushed to my father and said something to him, though I was not in any state to hear it. I was a silent spectator to this event.

I was suffocating from the smell of blood. I ran upstairs. My father and the other people went outside, to battle again.

It comes back to me every night. It makes me feel proud now — brave and courageous. But this is now. And that was then.

***

I ran. I opened the room and embraced my mother. I was crying. Tears were pouring out. I told her the whole story, crying and hugging her. It gave me solace to tell her everything. I told her what I had seen. I told her how my father had beheaded 26 women of his own clan, I told her how every one of those women came forward to get slain. I told her everything.

I was still crying. She closed her eyes. A tear rolled down her cheek and assembled at her chin. She sighed, 'waheguru.'

Her calmness and silence again pushed me into trauma. She didn't weep. She also seemed satisfied, as if everything had been planned, directed, and temporary. As if everything was going to be all right. As if those women would come back to life. As if.

I remember that it was 3:30 in the afternoon; the sun was in his full grace. The blue sky and the red ground provided a vivid contrast. The sky was kissing the earth. We again went to the window to witness the battle of life and honor, and also of stupidity and numbers.

The attackers were getting an upper hand. The villagers were already reduced to roughy a fifth of the force with which they had begun. Just a handful of brave people were still fighting. Several were bleeding; several had fallen; several were soon to fall.

The swords were clashing — sparks came out when the blades hit each other. Blood fountained. One of the attackers was a large man; he was slaying our villagers as if they were nothing. His every blow was lethal. He was cutting through the people. One of the villagers, with a long sword in his right hand and a shield in his left, ran towards him and jumped on him, a swift movement, his sword coming down on the attacker on the way down, slicing his ribs and exposing his bones. Now he was to the attacker's left, down and crouched after the jump. He traced the motion in reverse: this time he stood up in a rapid thrust and his sword cut just below the chin of the attacker, rupturing his neck. The big man fell to his knees and kissed the ground. He had not been ready for all this. It had come too fast.

My father was fighting at one corner of the courtyard, an area surrounded by houses on four sides. He was being attacked by three people. He was dodging and then attacking back. One of them got behind his back and swiftly cut through his right leg. He was in pain — I could see that from where I was. But my father was still was trying to fight. He jumped back and turned to his side. But one of the other two attackers shoved a blade through his back — it entered him from behind, pierced him, and then came out from his belly. It was a killing stroke. The attacker did not drew his sword out. He left it there. My father fell to his knees and then collapsed.

I was still a silent spectator. My father was killed. My mother again spoke, 'waheguru.' And I was still unaware of the cause of all that had happened over the last three days.

READ THE REST OF THE STORY AT THE BIG ROUNDTABLE.

This story originally appeared at The Big Roundtable. Writers at The Big Roundtable depend on your generosity. All donations, minus a 10 percent commission to The Big Roundtable and PayPal's nominal fee, go to the author. Please donate.