The fifth-grade baseball phenom

The Valdez family hustles to keep up with their son's mad dash from Little League legend to Major League dreamer

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

All eyes focus on Josue Valdez's 32-inch aluminum bat. The Riverbank Youth Baseball League MVP and Player of the Year completes his practice cuts and digs in to the batter's box. He crouches slightly, cocks his hands behind his right ear and wags his bat in anticipation. Teammates on each base clap and shout his name as he stares down the pitcher 45 feet away.

The rattling of chain-link fences and the raucous Riverbank Raptors nearly drown out a man on the loudspeaker calling out "No walks!" I learn from a teammate's father that the rule prevents other teams from walking Josue, intentionally or not. It applies to a handful of hitters in the league who used to get the Barry Bonds treatment.

The slugger's parents, Jose Valdez and Yahaira Mota-Valdez, inch closer to the fence for a better view of their "baby," a stocky 10-year-old who could pass for 12. Their cheers might be the loudest of all as the nervous pitcher winds and delivers a fastball.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

(More from Narratively: The Manhattanite with the world's largest dictionary collection)

Josue (pronounced ho-sway) started playing baseball when he was five and says he fell in love with the game by age seven. He rattles off Yankees statistics, mimics Jeter and A-Rod's batting stances and makes it clear to anyone who asks that his dream is to one day play in the big leagues. It's not a pipe dream, either. Mota-Valdez says that random people watching the games often come up to her to tell her how much potential they see in her son.

"I love playing ball," Josue says. "I love catching, hitting triples, hitting home runs. I could not imagine my life without baseball. I would be playing with my Xbox and would be bored."

The Valdezes, like millions of families around the country, have to make considerable financial sacrifices to keep their son's dream alive.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Josue, whom I taught 4th grade to at Harlem Success Academy last year, plays for two traveling teams, the Raptors, based in West Harlem, and the Kingsbridge Knights, based closer to his home in the Bronx. Between the two teams, he practices five nights a week and plays every weekend. Tournament entry fees alone have cost the family more than $2,000 this year, says his father, who manages a Radio Shack in Washington Heights.

The fact that Josue plays three positions — pitcher, catcher, and first base — all of which require different gloves and (in the case of catcher) special protective gear, makes him one of the costliest players to outfit. Although he does his best to find sales, Jose Valdez has spent nearly $1,000 this year on equipment, all of which Josue will inevitably outgrow.

The costs never seem to stop, says Mota-Valdez, who recently stopped working to go back to school for a bachelor's degree in speech pathology.

"There's all these little tapes and things Josue's always asking me to buy for him," she says. "The other night I spent $27 on the internet for a thumb protector."

Last month, the family traveled to Delaware for a weekend tournament, their first outside of New York. Mota-Valdez contemplated staying behind to reduce the cost, but she didn't want to disappoint her son. Including a $250 entry fee, gas, food, and hotel accommodations, the trip's cost exceeded $1,000. On top of that, the Valdezes and other families pooled together extra money to pay the entry fee for one of Josue's teammates.

"I just can't say no to my baby," she adds, smiling.

(More from Narratively: From the bowels of a beast)

Once characterized by volunteer coaches, hand-me-down gloves, and sponsorships by local businesses, baseball has become a driving force in the $5 billion-a-year youth sports industry. Apparel and equipment manufacturers, tournament operators, and corporate sponsors have transformed the pick-up games of old into a profit-driven enterprise.

As companies like Nike and Easton make millions, many families are being priced out of America's pastime. Participation in youth baseball fell 24 percent from 2000 to 2009, according to the National Sporting Goods Association. Much of the drop has come from community-based Little Leagues, which saw their rolls drop from 2.5 million in 1996 to about 2 million last year.

The decrease is especially pronounced in inner cities, despite the efforts of youth organizations such as Harlem RBI — which stands for "Reviving Baseball in Inner Cities" — to keep the game alive. In the late 1980s, nearly 20 percent of major league players were African-American. Today, that number has fallen to about 8 percent. Earlier this year, MLB commissioner Bud Selig formed a 17-member diversity committee to investigate the falling-off.

(More from Narratively: The dangerous world of NYC street racing)

"I don't want to miss any opportunity here," Selig told The New York Times in April. "We want to find out if we're not doing well, why not, and what we need to do better."

The rising cost of the game is likely not the only cause for the drop, but the correlation is hard to ignore, especially when considering that participation in cheaper sports like basketball and soccer has remained steady.

Despite the decline in players, profits for Little League Inc. are at record highs. The nation's oldest and largest youth baseball organization just signed an eight-year, $60 million deal with ESPN to continue broadcasting the Little League World Series, which brought in $6 million in corporate sponsorships last year. Were he still alive, the current level of profiteering might appall Carl Stotz, who founded the organization in 1939 on strict principles of volunteerism and sportsmanship. He was ousted in 1955 after he fought to impede the interests of U.S. Rubber, the first corporate sponsor.

When it comes to making money off of kids' dreams, however, travel ball dwarfs Little League. The one sector of the youth baseball population that has seen a surge since the 1990s is the number of kids who play more than 50 games a year — kids like Josue. Traveling teams have become popular because they offer families more games, higher quality coaches, better competition, and, in many cases, year-round training. Whereas travel ball used to complement community leagues by providing stronger players an option for continued play through the late summer months, it now pulls away the most talented players and places them in expensive tournaments that are economic gold mines for the host cities.

Read the rest of this story at Narratively.

Narratively is an online magazine devoted to original, in-depth and untold stories. Each week, Narratively explores a different theme and publishes just one story a day. It was one of TIME's 50 Best Websites of 2013.

-

Democrats seek calm and counterprogramming ahead of SOTU

Democrats seek calm and counterprogramming ahead of SOTUIN THE SPOTLIGHT How does the party out of power plan to mark the president’s first State of the Union speech of his second term? It’s still figuring that out.

-

Climate change is creating more dangerous avalanches

Climate change is creating more dangerous avalanchesThe Explainer Several major ones have recently occurred

-

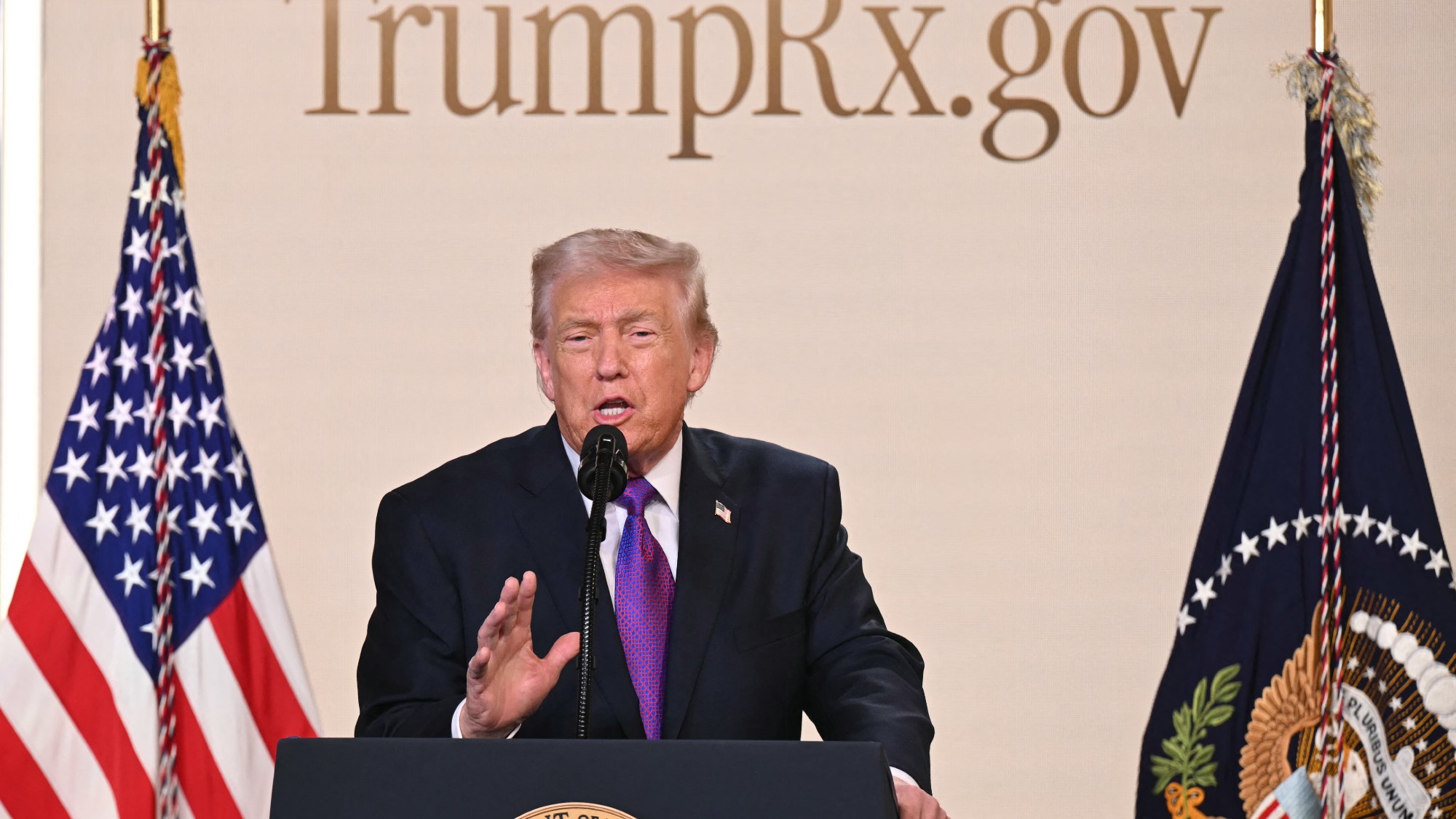

What’s TrumpRx and who is it for?

What’s TrumpRx and who is it for?The Explainer The new drug-pricing site is designed to help uninsured Americans