The man with the killer pitch

In 1916, Tom "Shotgun" Rogers earned himself a piece of baseball immortality — by killing a former teammate with a fastball

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

They called him "Shotgun" Rogers. In 1916, Nashville Vols pitcher Tom Rogers earned that nickname with a fastball that called a cannon to mind, and what, in the sports-writing parlance of the day, might have been called "sterling displays of boxwork." He won 24 games for the minor league club that year, and led the team to the Southern Association championship. In an era before television, before radio, when small towns saw big leaguers only during rare off-season barnstorming trips, these independent clubs were the only game in town. In Davidson County, Rogers was a hero, a country boy made good in the big city. But on June 18, 1916, Shotgun Rogers, aka the Gallatin Gunner, earned his deadly nickname a second time around.

Pitching in Mobile against the Sea Gulls, Rogers launched one of his famous fastballs at Johnny Dodge, a smooth-handed third baseman who had played in Nashville the year before. A happy-go-lucky type sometimes criticized for a lack of commitment to the game, Dodge had — according to the Tennessean's Blinkey Horn — "recently coupled his latent faculties with self mastery."

"When that juncture was reached," wrote Horn, "his success was assured."

Article continues belowThe Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

But Dodge also had a nasty habit of "running out into the diamond to meet a curve before it broke" — an unorthodox bit of the gamesmanship that has long since disappeared from the sport. That day in Mobile, Dodge ran to meet Rogers' pitch, but the ball did not curve. At "cannon-speed," it sailed into Dodge's face and "knocked him to the ground like a log." A "hasty examination" suggested he would recover. He didn't, dying of a brain hemorrhage after passing out in the clubhouse showers.

Contemporary accounts tell us nothing about Rogers's reaction. In those days, ballplayers' private lives were private, in victory and in tragedy. Rogers is not quoted in the newspaper accounts of Dodge's death, and there is no way to really know how the on-field catastrophe affected him. But the newspapers do record that, three weeks after his fastball killed Johnny Dodge, Shotgun Rogers threw a perfect game.

(More from Narratively: Art of the underground)

It's a fine example of a historical footnote. Just a few sentences in an obscure baseball history book — "Man kills former teammate; man throws perfect game" — that make one desperate to learn more. But there's not much more to learn. Newspaper accounts of the perfect game, though lavish in their praise of Rogers, neglect to mention Johnny Dodge. The dark side of the narrative is left out completely, making this footnote a reminder that in sports — as in plenty of other areas — narrative is malleable. When the facts are thin enough, the narrative can be whatever we want it to be.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

In those days, Nashville baseball was played at Sulphur Dell, which the New York Times once called "the world's most improbable ballpark." The playing area was mitten-shaped: long to left field and center, but just 262 feet to right, where the wall was topped by a screen 10 feet taller than the Green Monster. Outfielders were known as "mountain goats" because of the outfield "dump," a steep hill that, in right field, rose as high as 22.5 feet and earned the park the nickname "Suffer Hell."

Low-lying, swampy and cramped, the Dell was a stopover for Major League teams coming up from spring training, and on April 7, 1927, the state legislature adjourned early to watch the Yankees play the Cardinals.

"I'd read that Babe Ruth took one look at the park when he came through the dugout," says Skip Nipper, author of Baseball In Nashville, "and said, 'I'm not playing right field, because I wouldn't play on anything a cow wouldn't graze on.'"

(More from Narratively: An NYC crime photographer tells all)

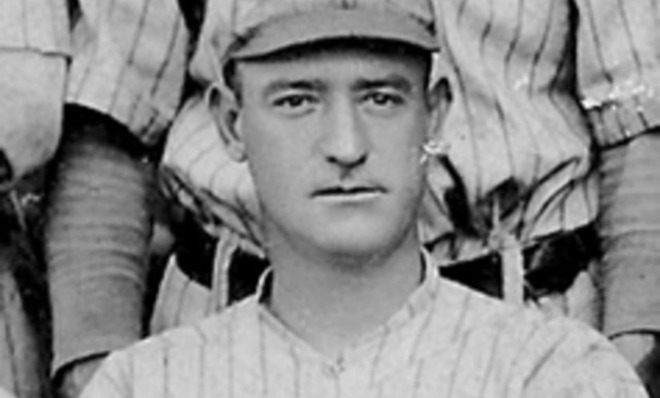

It took two days for the news of Dodge's death to filter back to Nashville. In the Tennessean of July 19, it's simply mentioned that the game was "weird," that Rogers's fielding was "miserable," and that Dodge took one to the forehead in the seventh. The next day, under a photo of Dodge in action, Horn gives his eulogy, leading with the news that "The Great Umpire has called Johnny Dodge out."

The on-field death, Horn tells us, was "without a parallel in Dixie," and it was the last in the minor leagues until 2007, when a line drive claimed the life of Mike Coolbaugh, first base coach for the Tulsa Drillers. After Coolbaugh's death, the Houston Chronicle interviewed Jane Thomson — Rogers' 85-year-old niece — to ask about the man her uncle killed. According to her, Rogers and Dodge had been close friends, rooming together for several years before the third baseman was traded to Mobile, and the accident destroyed the pitcher.

"When you kill your best friend, it just hurt him so much," Thomson told the Chronicle. "He just never could hold up anymore after that. He was his friend. I don't know that it was guilt, but it was just such a tragedy."

(More from Narratively: Grandchildren of Holocaust survivors)

The incident haunted Rogers, she said, who drifted away from his fastball and, after an undistinguished major league career, died an alcoholic at 44. His widow, Edna Rogers, said that on certain nights Rogers would stand by the roadside and pass envelopes into a car window — financial support for Johnny Dodge's family. Shotgun was not a happy killer.

It's natural for the Rogers family to believe their uncle heartbroken, and it may well be true. But it's not possible to know what Tom Rogers was thinking on July 11, 1916, when he achieved what in baseball passes for immaculate: a perfect game, which Blinkey Horn described with his trademark twisted prose as "one unmarred by either a run, a hit or a hostile son of swat reaching the initial corner."

Read the rest of the story at Narratively.

Narratively is an online magazine devoted to original, in-depth and untold stories. Each week, Narratively explores a different theme and publishes just one story a day. It was one of TIME's 50 Best Websites of 2013.