The intern who stripped on the side

Sure, I didn't like doing it, but what was the alternative? Working at Starbucks?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

They called it the "new" Times Square. I dodged tourists to get to work. There was always a man standing at the corner of 50th Street and Broadway in a yellow vest that read "Flashdancers," passing out little cards to all the men who walked by. One day, I asked him for one. He looked at me. "I work there," I said. He handed me a card.

On the card was a picture of a topless woman who did not work at Flash. Come visit me, it read. It was a free pass to get in.

I was attending Antioch College at the time, and they had a program called "co-op," wherein students alternated semesters on campus with terms of work or volunteer experience anywhere in the world. That fall, I had arranged to "co-op" in New York City, working at a nonprofit afterschool program for economically disadvantaged girls. But more importantly, when I'd made the arrangements I'd also set my sights on stripping in New York City, becoming part of an industry more glamorous and lucrative than any I'd come into contact with. Stripping was something I'd been doing since my sophomore year, when I found myself out of money while on co-op in Mexico. After that, I'd worked at two domestic violence shelters in Ohio, as a rape crisis counselor and at a Somali women's health organization in London. To afford to live during the unpaid internships so often taken for granted as part of the undergraduate experience, I stripped.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Through two years working off and on in the industry, I'd become more and more dependent on it. I relied on the income, but it was more than that. Outside of work, I kept mostly to myself. Few people knew the true details of my life. Ordinary human engagement ran risks and involved such censure that it hardly felt worth it. Without many friends or hobbies, and with few outside interests, sex work had become necessary not just for my economic survival, but for my social needs and emotional sustenance as well.

At the clubs back in Ohio, I had stood out as exceptional — more educated and, in my opinion, prettier than my coworkers. In New York City, I quickly learned this wouldn't be the case. My first week in the city, I grabbed a Village Voice, flipped to the back page, made a list of clubs and set out on foot. More than one manager looked me up and down before handing me a paper application without asking for so much as an audition. Most never called back.

New York Dolls was a sports bar up front and a cabaret in the back. It wasn't as nice as some of the other places I'd auditioned, but business was steady and the money was good.

I'd been working at Dolls for just over a week when the events of September 11 turned downtown Manhattan into "Ground Zero" and we were out of jobs. I showed up at Flashdancers — Dolls' sister club in Times Square — pretending my manager at Dolls had sent me. This was how I came to work at Flash.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

(More from Narratively: Sex, love, and loss in gay cyberspace)

Welcome to the world-famous Flashdancers. The house fee is $150 a night. Each dancer pays her house fee when she walks through the door. Arrive 20 minutes before the start of your shift. Get there a minute late and risk being fined. More than five minutes late and you might be sent home. At Flash, the rules were strict and we girls were expected to follow them. I tried to follow the rules. I wanted to fit in.

Whereas other clubs I'd worked in would hire girls of all sizes and descriptions, the girls who worked as Flashdancers had a certain look. Everyone was tan with long hair, long nails, and drag-queen makeup. Most girls were tall, with big tits and small waists. No imperfections — no scars, no stretch marks, no body fat. With a little work, I fit the bill. Without it, I was a normal-looking girl with a normal woman's body. Good enough, I remember thinking often, but not good enough for Flash.

The girls who worked at Flash were professionals. I was competing with women five inches taller than I was. Ten pounds lighter. Girls with advanced degrees. Girls from places where people only dreamt of making the kind of money a girl could make at Flash. At Flash, a girl could make as much as $1,000 a night. After our house fee and the requisite tipping — D.J., floor staff and house moms (the women in the dressing room who watched our stuff and did our makeup) — we kept whatever we made: $20 per lap dance, plus whatever tips we were given while onstage.

When I arrived, the dressing room was packed. It was house policy that dancers not have tattoos, so we girls who had them — nearly all of us — had to cover them with makeup. I had five by then, all butterflies, zigzagging up my left side. I got my tattoos covered, tipped the house mom a twenty, and got in line.

(More from Narratively: The hair down there)

The D.J. called Flashdancers "The United Nations of Strip Clubs." At the beginning of the shift, we'd do the parade. Nearly 100 girls from all over the world walked across the stage in a line as the D.J. rattled off our names in alphabetical order: Alex, Alexandria, Alexis, Amanda, Anna, Anita — the list went on and on.

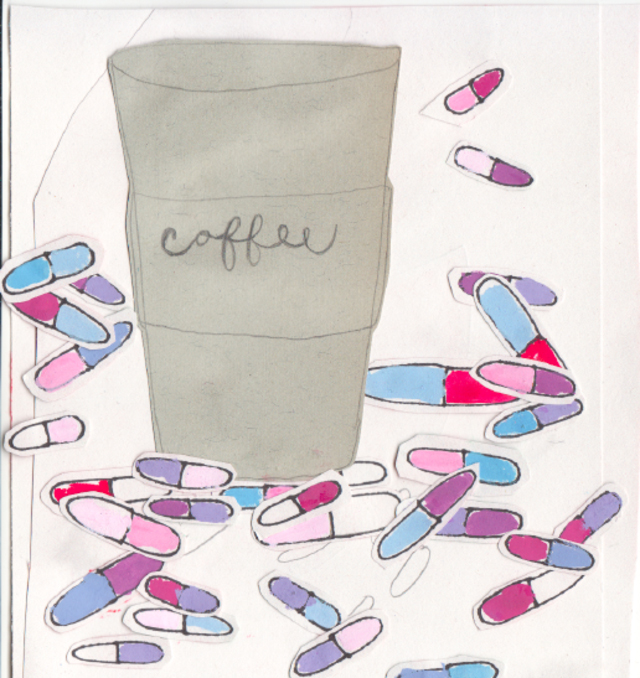

After the parade, we congregated to the right side of the stage. Most nights, I sat down at a table with two Russian girls and a black girl named Snow. I started each shift with a cup of black coffee and a handful of Xenadrine. A month after I'd started taking them, I was up to four pills at a time — double the recommended dose. The effect was something like the revving of an engine or the booting up of a computer. When a group of guys walked in, Snow and I wasted no time.

"Who's ready for a dance?" Snow asked.

Two guys volunteered themselves. I took my customer by the hand and led him to the vinyl benches where the private dances took place.

"I really like this song," I said.

"Oh yeah?"

"Yeah. I'm going to make this dance extra special."

As I positioned myself between his legs, he put his hands on my thighs. I took his hands, as though it were part of my act, and put them back on his lap. He let out a dramatic sigh. Look, I thought, they're not my rules. I might not have cared, but Flash was strict. They told you what to wear, how to dance, how to conduct yourself when sitting with a client. The money at Flashdancers was better than anywhere I'd worked before, and some might say I did a lot less to earn it. Still, with all their rules, there was little room for personality. I sometimes missed the trashier places in Ohio, where I could be more like myself.

When the song came to an end, he reached for his wallet. On cue, I started getting dressed. I looked back to the table to see that Snow had already moved on. That table's burnt, I thought. I scanned the room for my next twenty bucks.

(More from Narratively: The life of female cabbies in New York)

Tonight, I tell myself at the start of each night, I'm going to make a lot of money. Find a table celebrating some guy's birthday. Give the birthday boy a dance. Lead him by the hand to the corner of the room. Become one of 100 girls, bodies aslant, naked in tangerine skin. Vacant face, like a magazine ad. Part your lips, smile coy. Turn, bend over. Rinse and repeat. Change your costume every hour. Sequins to feathers to spandex to lace. Have a drink or two to loosen up. Have another when you're on a roll. Try something on for one customer; discard it for the next.

Tell me about your job.

That is so interesting.

You sound so important.

I am really starting to like you.

I really like you, honest I do.

I think I'm starting to fall for you.

You smile like you love it, you laugh like it's funny. You act as if you're having fun. The truth was that it wasn't fun, not anymore. Had I been able to be honest with myself, I would have had to admit that it had stopped being "fun." Sure, some nights, something interesting might happen. Most nights, though, were all the same. It was an easy, comfortable, familiar feeling, but I would not have described it as "fun." I told myself it was work — a job like any other. But what other job, I'd argue with myself, would pay me like this one? How else could I both work and go to school? Sure, I didn't like doing it, but what was the alternative? Working at Starbucks? No way, I told myself. I was worth more than that.

Read the rest of the story at Narratively.

Narratively is an online magazine devoted to original, in-depth and untold stories. Each week, Narratively explores a different theme and publishes just one story a day. It was one of TIME's 50 Best Websites of 2013.

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day