How birth control became everybody's business

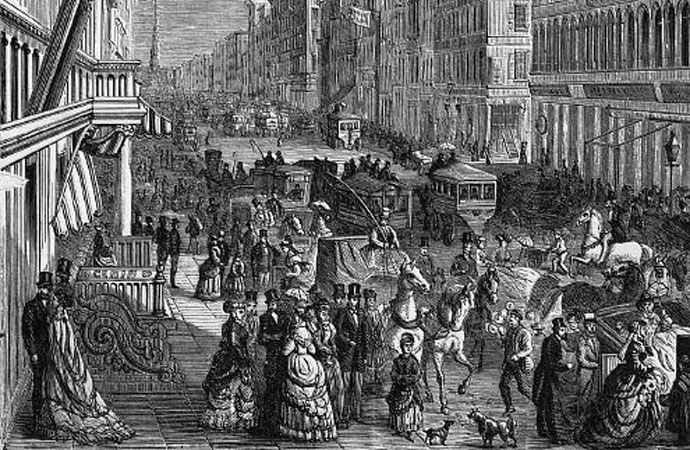

In the 1800s, what was once a personal choice became an issue of public decency

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

This October marks the 97th anniversary of the opening of the first Birth Control Clinic, in Brooklyn. It was opened by Margaret Sanger, who founded the American Birth Control League (which would later become Planned Parenthood). The clinic remained open for nine days before police shut it down and arrested Sanger for distributing obscene materials.

Before the mid-19th century, birth control was the unspoken, private concern of women and their sexual partners. But in the 1800s, American society changed, and what was once a personal choice became an issue of public decency. The run-up to the opening of Sanger's birth control clinic is a fascinating — and troubling — story of tumultuous change and social engineering.

Vaginal plugs and sea sponges

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Birth control: The ability of a woman to control whether or not she conceives. Except the definition has never been as simple as that. The meanings change over time, but it's never just simple physiology. Today, those words have political baggage as the nation argues over what sort of medical coverage should be applied to birth control. A hundred years ago, when the term was brand new, it didn't simply describe a health choice. It represented all that was immoral, classicist, unhealthy, unwomanly, and illegal. It also represented salvation.

Before the mid-1800s, birth control was a private matter women attended to themselves. The medical community didn't care about it, and governments had no interest in regulating it. Peter C. Engelman is the author of A History of the Birth Control Movement in America and the associate editor of the Margaret Sanger Papers Project. According to Engelman, birth control has been utilized (to varying degrees of effectiveness) by women for all of history. The main methods were likely rhythm (abstaining during fertile periods) and withdrawal. But women, desperate to control how many times they got pregnant, were always willing to try more-creative options.

Says Engelman:

Most contraceptive methods date back to ancient times: Suppositories, vaginal plugs, sponges, pastes — made of locally available materials such as grass, seaweed, gum, lemons, honey, olive oil, paper, wool, cotton, and sea sponges. Almost anything that could be occlusive — creating a barrier — and/or acidic and spermicidal has been used.

It wasn't until the 19th century that a woman's private business became a public concern.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Cities, sin, and sex

The American Medical Association, which formed in 1847, wanted to instill respect for the emerging profession of "real" doctors. They wanted to distinguish themselves from quacks, patent medicine-men, midwives, and folk healers. A movement began within the medical community to discredit these practitioners and the medical processes most aligned with them. Birth control and abortion were at the top of the list.

At the same time, attitudes toward sexual morality began to change after the Civil War. Cities grew larger, attracting single men and the vices they brought with them. Says Engelman, "Essentially a new morality movement blossomed in the postwar period — a reaction in large part to an increase in prostitution, venereal disease, and pornography, especially in urban centers. Urbanization and industrialization drew more single men and new immigrants into cities and more women into the workplace, creating more opportunities for non-marital sexual unions. A purity movement brought together temperance advocates and moral reformers who associated contraception with obscenity, prostitution, promiscuity."

Loud voices began to proclaim from pulpit and pamphlet that to block God and Nature from their desired course was an abomination. Preventing conception was indistinguishable from abortion to many and was seen as the violent interference of an intended life. (Ironic, as one of the intentions of birth control pioneers was to prevent unnecessary abortions). Not to mention, limiting the number of children you conceived was poor long-term planning before the 20th century. Only a percentage of those children were expected to survive to adulthood, and those that did would need to help you survive in turn.

Still, women continued to privately practice their imperfect birth control, whatever way they could. It's not like it was illegal.

The nation's chastity belt

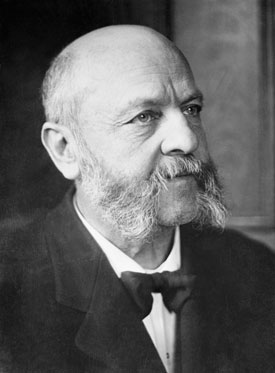

Until the Comstock Act. Anthony Comstock (pictured, left) can lightly be considered one of the biggest wet blankets in American history, or darkly considered a great stumbling stone to human rights. In the mid-19th century, Comstock worked in New York as a salesman. There, he became a self-appointed crusader for decency, working as a volunteer police informant to stop prostitution and other indecencies. He became so deeply devoted to the cause of decency that he drafted his own anti-obscenity bill, which was not only reviewed by Congress, but passed into law in 1873.

The law now prevented the printing, sale, or distribution of sexually obscene literature or devices through the mail. This included birth control and information about birth control. In effect, Comstock made it a federal offense to educate people about safely preventing conception. Individual states quickly adopted more detailed versions of the law. In Connecticut, it was illegal for a married couple to use any form of contraception within the privacy of their own bedroom, with prison terms up to one year if convicted. Thankfully, the police usually didn't make this sort of investigating a top priority. As late as 1960, 30 states still had laws based on Comstock's birth control laws on their books.

So when the occasional 19th century text did touch on the subject, it was often vague to the point of confusing. Dr. Munro devoted just a single paragraph to the subject of "excessive pregnancies" in his 1888 book The Ladies' Guide to Health in 1888. To the prevention of pregnancies, he gave two sentences.

[Excessive pregnancies] are an outrage on humanity, and husbands are principally to blame. Let those whom it may concern "defraud" each other "with consent for a time."

This, Google tells me, is a Biblical reference to occasional sexual abstinence between married couples, and is all the advice this doctor had to give. It was opaque silence like this and the fatalities it caused that would eventually galvanize one of the greatest proponents of birth control: Margaret Sanger.

"Unrestrained indulgence is their motto"

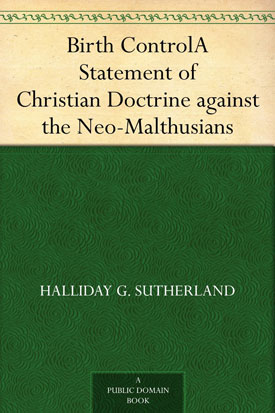

If you wished to condemn birth control, you could print and circulate literature for as long as the ink and paper held out. A great example is Halliday Sutherland, in his 1922 text Birth Control: A Statement of Christian Doctrine Against the Neo-Malthusians (a derogatory term for people who agreed with the Reverend Thomas Robert Malthus and his theories about the danger of population growth).

Sutherland really wanted you to understand how devastating any kind of birth control could be. It would leave you insane, sterile, and bound for hell.

Sutherland quoted studies that showed a woman's maternal passion would eventually outweigh her sexual passion (which she'd selfishly chosen to gratify), but the foolish use of contraception would have caused her ovaries to atrophy anyway. Her longing for motherhood would eventually result in incurable neuroses.

Sutherland also wanted it to be known that a man who "uses" his wife only for sexual pleasure is basically utilizing her as a prostitute. He decried the animalistic nature of birth control, saying of its proponents "Unrestrained indulgence, without the risk of consequences, is their motto."

"A Dragged Out Shadow of the Woman You Once Were."

It may take as little as two sentences to indicate why Margaret Sanger became obsessed with birth control. Margaret's mother, Anne Higgins, endured 18 pregnancies in 22 years, 11 of which resulted in live births. She died at the age of 50, from cervical cancer and tuberculosis.

So Sanger knew of what she spoke when she said:

We see hordes of children whose parents cannot feed, clothe, or educate even one half of the number born to them. We see sick, harassed, broken mothers whose health and nerves cannot bear the strain of further child-bearing. We see fathers growing despondent and desperate, because their labor cannot bring the necessary wage to keep their growing families.

Sanger also worked as a nurse, attending to women seriously injured from self-inflicted abortions. She would later recall women begging the attending doctor for information on how to prevent this from happening again. All he would tell them would be to stop having sex, something that, for many married women of the day, wasn't a legitimate option. A husband had his rights. The story goes that it was immediately after the death of one such patient, who had pleaded for birth control education and received none, that Sanger began her crusade.

She empathized with the unseemliness of birth control — how unromantic and sordid douching, pessaries, and suppositories are before lovemaking — but, she added, "it is far more sordid to find yourself several years later burdened down with half a dozen unwanted children, helpless, starved, shoddily clothed, dragging at your skirt, yourself a dragged out shadow of the woman you once were."

Shortly after her birth control clinic was shut down, Sanger wrote and began (illegally) distributing the pamphlet entitled "Family Limitation," in which Sanger detailed, with an unmistakable voice of urgency, all the conventional ways a woman of that day could prevent conception. She described the devices available (pessaries, sponges, condoms, douches, suppositories) and precisely how to use them. She included recipes for the home manufacture of spermicides. It was precisely the kind of obscenity Comstock had been trying to prevent, and it fueled a war of morality and human rights every bit as bitter as the ones we have about abortion and gun control today.

Therese O'Neill lives in Oregon and writes for The Atlantic, Mental Floss, Jezebel, and more. She is the author of New York Times bestseller Unmentionable: The Victorian Ladies Guide to Sex, Marriage and Manners. Meet her at writerthereseoneill.com.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day