Strategize smarter

A primer on strategy

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

There are many good reasons to read Good Strategy Bad Strategy by Richard Rumelt.

You may be frustrated by the state of your organization's strategy. You may be interested in identifying the characteristics of good strategy. Or you may want to learn how to identify the elements of a bad strategy.

A leader's most important responsibility is identifying the biggest challenges to forward progress and devising a coherent approach to overcoming them. In contexts ranging from corporate direction to national security, strategy matters. Yet we have become so accustomed to strategy as exhortation that we hardly blink an eye when a leader spouts slogans and announces high-sounding goals, calling the mixture a "strategy."

Complexity

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

"A hallmark of mediocrity and bad strategy," Rumelt writes, "is unnecessary complexity — a flurry of fluff masking an absence of substance." Most bad strategies are nothing more than statements of desire. And if you read them closely, the goals often contradict one another.

This book should be required reading for managers and executives alike.

The strategy retreat

I'm sure this excerpt sounds familiar to many of you:

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The event was a "strategy retreat." The CEO had modeled it on a similar event at British Airways he had attended several years before. About two hundred upper-level managers from around the world gathered in a hotel ballroom where top management presented a vision for the future: to be the most respected and successful company in their field. There was a specially produced motion picture featuring the firm's products and services being used in colorful settings around the world. There was an address by the CEO accompanied by dramatic music to highlight the company's "strategic" goals: global leadership, growth, and high shareholder return. There were breakouts into smaller groups to allow discussion and buy-in. There was a colorful release of balloons. There was everything but strategy. [Good Strategy Bad Strategy]

Good strategy is the exception not the rule. Rumelt argues that the bad strategy problem is only growing. Even worse, more and more leaders think they have a strategy when they do not — they have a bad strategy. Bad strategy, "ignores the power of choice and focus, trying instead to accommodate a multitude of conflicting demands and interests." Sounds familiar?

What is a bad strategy?

Bad strategy is long on goals and short on policy or action. It assumes that goals are all you need. It puts forward strategic objectives that are incoherent and, sometimes, totally impracticable. It uses high-sounding words and phrases to hide these failings. [Good Strategy Bad Strategy]

Underperformance is a result

When a leader characterizes the challenge as underperformance, it sets the stage for bad strategy. Underperformance is a result. The true challenges are the reasons for the underperformance. [Good Strategy Bad Strategy]

Good strategy

Good strategy is not just "what" you are trying to do. It is also "why" and "how" you are doing it. … Good strategy requires leaders who are willing and able to say no to a wide variety of actions and interests. Strategy is at least as much about what an organization does not do as it is about what it does. [Good Strategy Bad Strategy]

Strategy is not vision or ambition

Despite the roar of voices wanting to equate strategy with ambition, leadership, "vision," planning, or the economic logic of competition, strategy is none of these. The core of strategy work is always the same: discovering the critical factors in a situation and designing a way of coordinating and focusing actions to deal with those factors. A leader's most important responsibility is identifying the biggest challenges to forward progress and devising a coherent approach to overcoming them. In contexts ranging from corporate direction to national security, strategy matters. [Good Strategy Bad Strategy]

The core of strategy has three elements

The kernel of a strategy contains three elements: a diagnosis, a guiding policy, and coherent action. The guiding policy specifies the approach to dealing with the obstacles called out in the diagnosis. It is like a signpost, marking the direction forward but not defining the details of the trip. Coherent actions are feasible coordinated policies, resource commitments, and actions designed to carry out the guiding policy. [Good Strategy Bad Strategy]

Coherence of design

A good strategy doesn't just draw on existing strength; it creates strength through the coherence of its design. Most organizations of any size don't do this. Rather, they pursue multiple objectives that are unconnected with one another or, worse, that conflict with one another. [Good Strategy Bad Strategy]

Coordination is costly and hard

Coordination is costly, because it fights against the gains to specialization, the most basic economies in organized activity. To specialize in something is, roughly speaking, to be left alone to do just that thing and not be bothered with other tasks, interruptions, and other agents' agendas. As is clear to anyone who has belonged to a coordinating committee, coordination interrupts and de-specializes people. [Good Strategy Bad Strategy]

Good strategy is actually surprising

Most complex organizations spread rather than concentrate resources, acting to placate and pay off internal and external interests. Thus, we are surprised when a complex organization, such as Apple or the U.S. Army, actually focuses its actions. Not because of secrecy, but because good strategy itself is unexpected. [Good Strategy Bad Strategy]

Focus, however, is hard. It means saying no to individuals, groups, and even entire lines of business.

The inside view describes the fact that people tend to see themselves, their group, their project, their company, or their nation as special and different. [Good Strategy Bad Strategy]

Increasing value…

In particular, increasing value requires a strategy for progress on at least one of four different fronts: deepening advantages, broadening the extent of advantages, creating higher demand for advantaged products or services, or strengthening the isolating mechanisms that block easy replication and imitation by competitors. [Good Strategy Bad Strategy]

Unfinished thought

As I was reading this book I kept wondering why organizations were so reluctant to employ a strategy. All of this thinking reminded me of another book I had read a few years back on strategy called The Strategy Paradox.

What is the paradox?

The most profitable strategies are "extreme" strategies that commit companies to positions of either product differentiation or cost leadership. These extreme positions expose firms to a greater likelihood of bankruptcy by increasing the strategic risk they face. Consequently, the strategies likeliest to succeed are also likeliest to fail. That is the strategy paradox. [The Strategy Paradox]

At first I thought that maybe organizations avoided good strategy simply because it was complicated and involved hard choices. The more I thought about it, however, the more I settled on the fact that people avoid good strategies because they don't want to be wrong.

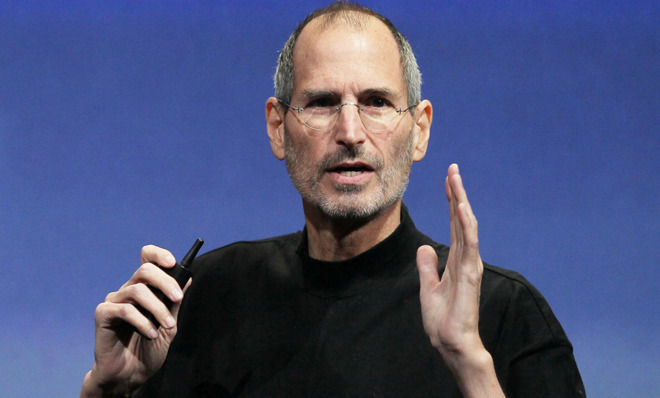

When Steve Jobs took over Apple, he did the unexpected.

What he did was both obvious and, at the same time, unexpected. He shrunk Apple to a scale and scope suitable to the reality of its being a niche producer in the highly competitive personal computer business. He cut Apple back to a core that could survive.Steve Jobs talked Microsoft into investing $150 million in Apple, exploiting Bill Gates's concerns about what a failed Apple would mean to Microsoft's struggle with the Department of Justice. Jobs cut all of the desktop models — there were fifteen — back to one. He cut all portable and handheld models back to one laptop. He completely cut out all the printers and other peripherals. He cut development engineers. He cut software development. He cut distributors and cut out five of the company's six national retailers. He cut out virtually all manufacturing, moving it offshore to Taiwan. With a simpler product line manufactured in Asia, he cut inventory by more than 80 percent. A new Web store sold Apple's products directly to consumers, cutting out distributors and dealers.What is remarkable about Jobs's turnaround strategy for Apple was how much it was "Business 101" and yet how much of it was unanticipated. [Good Strategy Bad Strategy]

In May 1998, shortly after taking over Apple, Jobs explained the substance and coherence of his actions:

The product lineup was too complicated and the company was bleeding cash. A friend of the family asked me which Apple computer she should buy. She couldn't figure out the differences among them and I couldn't give her clear guidance, either. I was appalled that there was no Apple consumer computer priced under $2,000. We are replacing all of those desktop computers with one, the Power Mac G3. We are dropping five of six national retailers — meeting their demand has meant too many models at too many price points and too much markup. [Good Strategy Bad Strategy]

Jobs' actions were both focused and decisive and, in hindsight, correct. Everyone at the time was surprised because they expected the fluffy goals and vacuous promises typical of most executives. But Jobs back-to-business 101 approach was correct. Jobs had a sick business and he needed to fix it.

While Jobs' turnaround at Apple was impressive it wouldn't enable Apple to become more than a niche player in an industry dominated by network effects. In 1998 Rumelt had a chance to ask Jobs, "What is the strategy? (going forward)" Jobs responded simply "I am going to wait for the next big thing."

This encounter struck Rumelt as different. Everywhere he went and everyone he talked to just spewed the same cliche's about their strategy — network relationships, adopting best practices, etc.

Rumelt writes:

Jobs did not enunciate some simple-minded growth or market share goal. He did not pretend that pushing on various levers would somehow magically restore Apple to market leadership in personal computers. Instead, he was actually focused on the sources of and barriers to success in his industry — recognizing the next window of opportunity, the next set of forces he could harness to his advantage, and then having the quickness and cleverness to pounce on it quickly like a perfect predator. There was no pretense that such windows opened every year or that one could force them open with incentives or management tricks. He knew how it worked. He had done it before with the Apple II and the Macintosh and then with Pixar. He had tried to force it with NeXT, and that had not gone well. It would be two years before he would make that leap again with the iPod and then online music. And, after that, with the iPhone.Steve Jobs's answer that day — "to wait for the next big thing" — is not a general formula for success. But it was a wise approach to Apple's situation at that moment, in that industry, with so many new technologies seemingly just around the corner. [Good Strategy Bad Strategy]

In hindsight we know Jobs' strategy worked but it could have just as easily backfired. The turnaround might have failed and landed Apple, now the world's largest company, in bankruptcy. Apple's strategy at the time wasn't easy to like — in fact, many people thought he was wrong. I imagine that Jobs would have been okay with being wrong — he was more worried about being mediocre.

We equate strategy with success but they are different things.

Real strategies — good strategies — can be wrong. And we don't want to be wrong. We're playing not to lose rather than playing to win. We all know how it feels to make a mistake — we'd rather watch other people make mistakes than make them ourselves. So we seek consensus because it's safe.

Yet consensus, when you think about it, is almost assured to fail. It's making everyone happy and alienating no one.

Consensus is the opposite of marshaling your resources towards a coordinated approach. And consensus, by definition, almost certainly assures a bad strategy because it doesn't make any choices. It's a sprinkle of this and a dash of that — it's something for everyone. Rather than risk being wrong, we hide behind puff that makes everyone happy. That's bad strategy.

The beauty of Good Strategy Bad Strategy is that it calls out the vast majority of public and private organizations that have horrible strategies. The bad news is that things are unlikely to change. After all, no one ever got fired for having a strategy to "increase the percentage of high school graduates." It's hard to argue with that as a goal but let's stop calling it a strategy.

If you're interested in learning more, watch this video of Richard Rumelt presenting at the London School of Economics:

There are plenty of good strategies out there. Lou Gestner developed one when he took over IBM in 1993 (for details see Gestner's book — Who Says Elephants Can't Dance?: Leading a Great Enterprise through Dramatic Change). He understood the problem and devised an approach that marshaled the organization towards dealing with the problem.

If you're still curious, read the entire book.

Shane Parrish is a Canadian writer, blogger, and coffee lover living in Ottawa, Ontario. He is known for his blog, Farnam Street, which features writing on decision making, culture, and other subjects.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day