Practice makes perfect: Why you should rethink the way you train

If you're like most people, your performance has probably plateaued

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

You've probably been doing your job for a while. If you're like most people, your performance has plateaued. Simply put, you've stopped getting better at what you do.

Despite repetition, most people fail to become experts at what they do, no matter how many years they spend doing it. Experience does not equate to expertise, as Geoff Colvin writes in his excellent book Talent is Overrated.

In field after field, when it comes to centrally important skills — stockbrokers recommending stocks, parole officers predicting recidivism, college admissions officials judging applicants — people with lots of experience were no better at their jobs than those with less experience. [Talent Is Overrated]

Society has always recognized extraordinary individuals whose performance is truly superior in any domain. If I were to ask you why some people excel and others don't, you'd probably say talent and effort. These responses are either wrong, as is the case with talent, or misleading, as is the case with effort.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Conveniently, claiming that talent is the basis for success means we can absolve ourselves of our own performance (or, as the case may be, lack thereof). The talent argument, despite its popularity, is wrong. Yet research tells a very different story on how people become experts.

Research concludes that we need deliberate practice to improve performance. Unfortunately, deliberate practice isn't something that most of us understand, let alone engage in on a daily basis. This helps explain why we can work at something for decades without really improving our performance.

Deliberate practice is hard. It hurts. But it works. More of it equals better performance and tons of it equals great performance. [Talent Is Overrated]

Most of what we consider practice is really just playing around — we're in our comfort zone.

When you venture off to the golf range to hit a bucket of balls what you're really doing is having fun. You're not getting better. Understanding the difference between fun and deliberate practice unlocks the key to improving performance.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Deliberate practice is characterized by several elements, each worth examining. It is activity designed specifically to improve performance, often with a teacher's help; it can be repeated a lot; feedback on results is continuously available; it's highly demanding mentally, whether the activity is purely intellectual, such as chess or business-related activities, or heavily physical, such as sports; and it isn't much fun. [Talent Is Overrated]

Let's take a look at each of Colvin's claims to better understand what he means.

It's "designed specifically to improve performance"

The word designed is key. While enjoyable, practice lacking design is play and doesn't offer improvement.

In some fields, especially intellectual ones such as the arts, sciences, and business, people may eventually become skilled enough to design their own practice. But anyone who thinks they've outgrown the benefits of a teacher's help should at least question that view. There's a reason why the world's best golfers still go to teachers. [Talent Is Overrated]

But it's more than just the teachers' knowledge that helps — it's their ability to see you in ways you can't see yourself.

A chess teacher is looking at the same boards as the student but can see that the student is consistently overlooking an important threat. A business coach is looking at the same situations as a manager but can see, for example, that the manager systematically fails to communicate his intentions clearly. [Talent Is Overrated]

In theory, with the right motivations and some expertise, you can design a practice yourself. It's likely, however, that you wouldn't know where to start or how to structure activities. As Atul Gawande writes in The New Yorker:

Expertise, as the formula goes, requires going from unconscious incompetence to conscious incompetence to conscious competence and finally to unconscious competence. [The New Yorker]

Teachers, or coaches, see what you miss and make you aware of where you're falling short.

With or without a teacher, great performers deconstruct elements of what they do into chunks they can practice. They get better at that aspect and move on to the next chunk.

Noel Tichy, professor at the University of Michigan Business School and the former chief of General Electric's famous management development center at Crotonville, puts the concept of practice into three zones: The comfort zone, the learning zone, and the panic zone.

Most of the time we're practicing we're really doing activities in our comfort zone. This doesn't help us improve, because we can already do these activities easily. On the other hand, operating in the panic zone leaves us paralyzed as the activities are too difficult, and we don't know where to start. The only way to make progress is to operate in the learning zone, which includes those activities that are just out of reach.

Consider a chess tournament. As researchers in the journal Applied Cognitive Psychology write:

Skill improvement is likely to be minimized when facing substantially inferior opponents, because such opponents will not challenge one to exert maximal or even near-maximal effort when making tactical decisions, and problems or weaknesses in one's play are unlikely to be exploited. At the same time, the opportunity for learning is also attenuated during matches against much strong opponents, because no amount of effort or concentration is likely to result in a positive outcome. [Applied Cognitive Psychology]

"It can be repeated a lot"

Repetition inside the comfort zone does not equal practice. Deliberate practice requires that you should be operating in the learning zone and you should be repeating the activity a lot with feedback. Researchers in the journal Psychological Review explain:

Let us briefly illustrate the difference between work and deliberate practice. During a three hour baseball game, a batter may only get 5-15 pitches (perhaps one or two relevant to a particular weakness), whereas during optimal practice of the same duration, a batter working with a dedicated pitcher has several hundred batting opportunities, where this weakness can be systematically exploited. [Psychological Review]

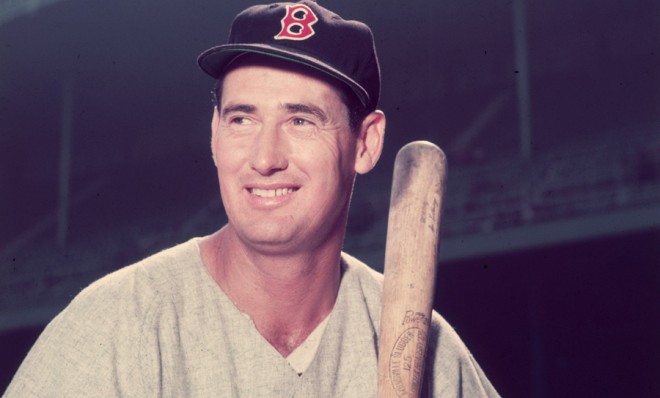

It's no coincidence that Ted Williams, baseball's greatest hitter, would literally practice hitting until his hands bled.

"Feedback on results is continuously available"

Practicing something without knowing whether you are getting better is pointless. Yet that is what most of us do everyday without thinking.

You can work on technique all you like, but if you can't see the effects, two things will happen: You won't get any better, and you'll stop caring. [Talent Is Overrated]

Feedback gets a little tricky when someone must subjectively interpret the results. While you don't need a coach, this can be an area they add value.

These are [the] situations in which a teacher, coach, or mentor is vital for providing crucial feedback. [Talent Is Overrated]

"It's highly demanding mentally"

Doing things we know how to do is fun and does not require a lot of effort. Deliberate practice, however, is not fun. Breaking down a task you wish to master into its constituent parts and then working on those areas systematically requires a lot of effort.

The work is so great that it seems no one can sustain it for very long. A finding that is remarkably consistent across disciplines is that four or five hours a day seems to be the upper limit of deliberate practice, and this is frequently accomplished in sessions lasting no more than an hour to ninety minutes. [Talent Is Overrated]

Still curious? Learn more about deliberate practice in Talent Is Overrated and this New Yorker article by Dr. Atul Gawande.

More from Farnam Street...

Shane Parrish is a Canadian writer, blogger, and coffee lover living in Ottawa, Ontario. He is known for his blog, Farnam Street, which features writing on decision making, culture, and other subjects.

-

Why is the Trump administration talking about ‘Western civilization’?

Why is the Trump administration talking about ‘Western civilization’?Talking Points Rubio says Europe, US bonded by religion and ancestry

-

Quentin Deranque: a student’s death energizes the French far right

Quentin Deranque: a student’s death energizes the French far rightIN THE SPOTLIGHT Reactions to the violent killing of an ultraconservative activist offer a glimpse at the culture wars roiling France ahead of next year’s elections

-

Secured vs. unsecured loans: how do they differ and which is better?

Secured vs. unsecured loans: how do they differ and which is better?the explainer They are distinguished by the level of risk and the inclusion of collateral