4 big accomplishments of the 1963 March on Washington

Fifty years ago today, Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his "I Have a Dream" speech. But there's more to remember than just that.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Today marks the 50th anniversary of the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. The event is most famous for the "I Have a Dream" speech delivered by Martin Luther King Jr. from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial to a crowd of some 250,000 people on the Washington Mall — and millions more via television.

When President Obama speaks today from the spot where King stood, he'll have some awfully big shoes to fill. Fifty years ago, on a hot afternoon following lengthy bus caravans and train rides, an actual march in Washington, then a morning of music and speeches about legislation and unemployment and racial injustice, King stepped to the lectern and "took a leap into history," says Michiko Kakutani in The New York Times:

Dr. King's speech was not only the heart and emotional cornerstone of the March on Washington, but also a testament to the transformative powers of one man and the magic of his words. Fifty years later, it is a speech that can still move people to tears. Fifty years later, its most famous lines are recited by schoolchildren and sampled by musicians. Fifty years later, the four words "I have a dream" have become shorthand for Dr. King's commitment to freedom, social justice, and nonviolence, inspiring activists from Tiananmen Square to Soweto, Eastern Europe to the West Bank. [New York Times]

Fifty years after King's speech and the other events of that remarkable day, there's a lot of talk about what has and hasn't changed in U.S. civil rights and racial equality, and how much of King's dream remains unfulfilled. Here are four concrete ways the March on Washington changed the U.S.:

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

1. The March created momentum for the Civil Rights Act

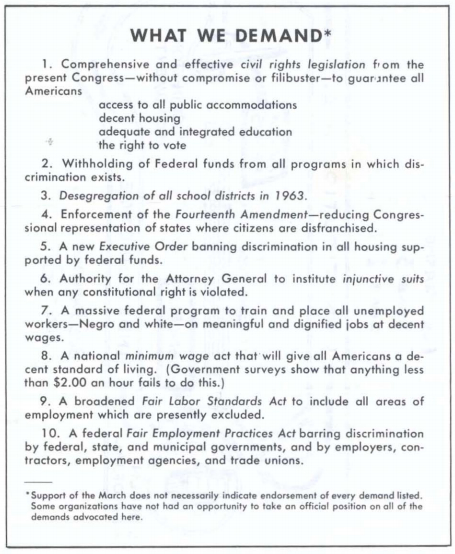

After King spoke, the event's key organizers, A. Philip Randolph and Bayard Rustin, read their demands of lawmakers to the crowd.

Looking over the demands now — among them, a $2-an-hour federal minimum wage, desegregation of all school districts, an enforcement of the 14th Amendment that reduces "congressional representation of states where citizens are disenfranchised" — some were eventually met while others weren't. But the principal demand was "comprehensive and effective civil rights legislation," and that came about within a year.

King's famous speech "was a message to the nation and the world, but its most immediate targets were the lawmakers nearby who would vote on the civil rights bill being worked on in the House," says Tom Brune at Newsday. President John F. Kennedy had just pledged to push such legislation, but he was concerned he couldn't get even a modest civil rights package through Congress.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The 1964 Civil Rights Act may not have made it through without President Lyndon B. Johnson's using Kennedy's assassination in November 1963 to build support for the law, but the March on Washington was a big factor, too, says Newsday's Brune. "Aug. 28, 1963, didn't change the minds of Southern Democrats or allied Republicans, but historians say it helped build popular support, especially among whites, for a civil rights revolution that transformed America's law and politics."

"Clearly, the march was a key factor in the enactment of the Civil Rights Act of 1964," says Michael Wenger at The Huffington Post, but that's not all. It also helped Johnson pass the the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and the Fair Housing Act of 1968. "And although it doesn't get sufficient credit for other legislation, the momentum it created was at least partially responsible for immigration reform, the war on poverty, and Medicare and Medicaid."

2. It made racism extremely uncool

It's easy to forget, but in 1963 blacks could be — and were — turned down for jobs and housing with impunity, says The Washington Post in an editorial. The March on Washington, with more than 200,000 blacks and whites gathered peacefully to demand greater equality, "was a symbolic moment, if not a turning point," the Post says.

While racial bigotry was not dead, it was no longer respectable, was not something that could be openly proclaimed by Cabinet officers, corporate leaders, even presidents of the United States. Its true shamefulness and cruelty became part of the national consciousness that day, expressed by King in forceful declarations and demands for equality, in biblical imagery and oratory, but also in simple images, none perhaps more enduring and meaningful to the great audience he sought to reach than that vision of children someday playing together with not a thought to the color of their skin. [Washington Post]

The March on Washington, and the laws it engendered, truly "changed the culture," says John McWhorter in The Wall Street Journal. To see how "personal racist sentiment rapidly became socially proscribed," you need look no further than the TV: "The Norman Lear sitcoms of the early 1970s, in which bigoted whites were regularly held up to ridicule, would have been unthinkable just 10 years before."

3. It sparked the career of the NFL's first black quarterback

Among those watching the March on Washington on their TV sets was James Harris, a high school football star in Monroe, La. When King spoke, "Harris felt jolted, as if King were speaking directly to him, to his deepest, most impossible desire," says Samuel G. Freedman in The New York Times: Being a pro football quarterback.

In 1963, when black football quarterbacks like Harris made it to the NFL, they "were routinely switched to receiver or defensive back," Freedman notes. The prevailing opinion at the time "was that a black man was not intelligent enough to play the position" of quarterback. "I had no chance, I knew that," Harris tells Freedman. "But then I started listening to that speech."

Inspired by King and the head football coach at Grambling State University, Eddie Robinson, Harris gambled on being quarterback at Grambling over playing receiver at the much more prestigious Michigan State, and it paid off, Freedman says:

Inspired by the speech, Harris became the first black player to be a regular, full-time starter at quarterback in the NFL. He was also the first to lead a team to a division title, to play in a conference championship, to be chosen for the Pro Bowl, and to lead a conference in passing efficiency. Heading into this NFL season, there is much hope resting on the shoulders of two young black quarterbacks: Robert Griffin III of the Washington Redskins and the Seattle Seahawks' Russell Wilson.... They owe their opportunity in part to Harris. [New York Times]

4. It saved the civil rights movement

Focusing on the March on Washington's "tangible accomplishments" misses "the most important consequence of the march," says Michael Wenger at The Huffington Post: It inspired and focused people "at a moment when anger and frustration threatened both the sense of hope and the courageous non-violence that had characterized the civil rights movement."

Things had been pretty ugly for the movement in 1963: Gov. George Wallace of Alabama had personally and bodily tried to stop the racial integration of the University of Alabama, King had been thrown in jail in Birmingham, and civil rights leader Medgar Evers was murdered outside his own home.

"Coming on the heels of the violent responses earlier to the sit-ins and the freedom rides, an increasing number of black people — and some white people, primarily northern college students — were being swayed by the more militant and angry rhetoric of Malcolm X," Wenger says. King's speech in particular "turned the anger and frustration with which many arrived that morning into a sense of empowerment far more powerful than anything we had felt until that day." If the march had fizzled or turned violent, it might well have been the "the death knell for the non-violent aspect of the movement," and maybe the movement itself.

Peter has worked as a news and culture writer and editor at The Week since the site's launch in 2008. He covers politics, world affairs, religion and cultural currents. His journalism career began as a copy editor at a financial newswire and has included editorial positions at The New York Times Magazine, Facts on File, and Oregon State University.