INTERVIEW: Jackie Robinson's pen pal talks baseball, race, and No. 42

"We were so different. I was white, he was black. I was Jewish, he was Christian. I was a kid, he was an adult."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

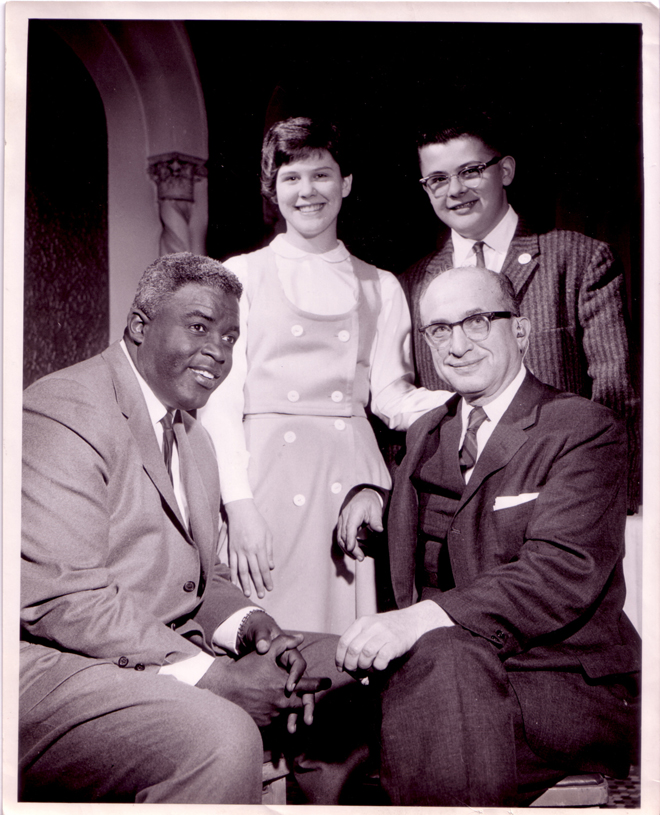

On April 15, 1947, Jackie Robinson broke Major League Baseball's color barrier when he appeared in his first pro game for the Brooklyn Dodgers. Halfway across the country, in the small city of Sheboygan, Wis., a little boy named Ronnie Rabinovitz watched Robinson's career take off and dreamed of one day meeting his hero.

When he was 7 years old, Rabinovitz got that chance, in a meeting that would spark a lifelong friendship carried on through letters, dinners, and baseball games, until Robinson's death in 1972.

With the DVD release this month of the documentary Letters From Jackie: The Private Thoughts of Jackie Robinson, I spoke with Rabinovitz, 67, who sells packaging materials in Minneapolis, Minn., and regularly travels the country speaking about Robinson and baseball. Here's a slightly edited transcript.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

How did you first get to know Jackie Robinson?

My father loved the Dodgers because they gave Jackie an opportunity to play. Well, unbeknownst to me, he wrote him a letter. Jackie wrote back with an autographed picture, and he said next time the Dodgers are in Milwaukee playing the Braves, he'd love to meet me.

Well, we went to a Dodgers-Braves game and we went down to the locker room and waited for him to come out. I went up to him and I said, "Jackie, I'm Ronnie Rabinovitz, do you remember me?" I was seven. And he says, "Sure I do." My dad is standing over my shoulder saying, "Sure, Jackie, of the thousands of letters you got?" And [Robinson] said, "No, I remember, because your dad wrote me on lawyer stationary." And from that point on we became the very dearest of friends.

How regularly did you speak with each other?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

We would correspond maybe two, three times a year. Maybe four times a year. As I got older, I'd call him — he gave me his unlisted phone number in Stamford, Connecticut. He was in Milwaukee playing the Braves about nine, ten times a year so we would spend time visiting then. He was even with me at my tenth birthday. We always got box seats on the third base side by the Dodgers' dugout. He hit a home run, and as he was rounding third he waved to me like that one was for me.

Afterwords, he had dinner with us. Just amazing to have Jackie Robinson sitting at my birthday dinner singing "Happy Birthday" to me. He also sent me a telegram when I graduated high school.

What did he say in the telegram?

"Congratulations. Sorry to have the late message. Have been out of the city. I'm always proud of your achievements. Continued good luck, Jackie Robinson."

Why you do you think he stayed in touch with you when he was getting so many fan letters from around the country?

I don't know the answer to that. We were so different. I was white, he was black. I was Jewish, he was Christian. I was a kid, he was an adult. I was from a small town in the Midwest, he was from out East. And yet there was this bond of friendship and love. Maybe Jackie's letters were like a baton toss, a black man of dignity was reaching out to touch a single boy who cared, and that boy passed that baton of brotherhood on to other children in the world. He once said, "A life is not important except for the impact it has on other lives." I don't know if he ever truly realized what a tremendous impact he had on mine.

Jackie broke the color barrier in baseball before the Civil Rights movement had fully gained steam, before Martin Luther King Jr. What role did he play in allowing that movement to take shape?

When you think about it, Jackie was alone. He was a true pioneer. Martin Luther King was a teenager. The Civil Rights movement hadn't started yet. So it was Jackie alone, and he took some tremendous, tremendous abuse. I think that's what contributed to his death so young at 53. He couldn't sleep with his team, he couldn't eat with his team. It was real tough. What he did for our culture is more powerful than just changing the face of sports and breaking down the color barrier. He changed all our lives. Martin Luther King once said, "Without Jackie, I couldn't have done what I did." He made it possible.

With all that hatred directed at Robinson, how did people respond to your interactions with him?

I had one particular friend I met in second grade. We were playing on the playground one day and he came up to me and said, "I can't play with you anymore." I said "Why?" and he said, "Because you're Jewish." I went home that night and thought about that. I cried, I was so devastated. I thought, "This is what Jackie's going through too."

That night my father went to [the kid's] home and talked to his parents. I don't know what was said, but the next day we were able to play together again. It was just ignorance. They had never met an African American, they had never met a Jewish person. And I took him to meet Jackie Robinson, and he became his hero too.

Did you realize at that young age the significance of him being the first black player in baseball?

At first, no. I loved him because he was helping my Dodgers win pennants. But as I grew up, as I got older, I realized how much more than just baseball he was, how much he did for this country. They say Babe Ruth changed baseball. Jackie Robinson changed America — and he did it alone.

This year, only 8.5 percent of all players on opening day rosters defined themselves as African American. The league is looking into the decline of African American players in the game and trying to address that issue. Is that something you're familiar with?

It's very disturbing to me to see this. It's almost like, well what did he do this for? I used to drive around neighborhoods, you saw kids playing ball on every corner. You don't see that as much anymore. They're inside on the computer, on television, playing basketball. It's such a great game and it's very sad to me that there aren't more African Americans. I think Major League Baseball is doing a good job trying to change that, but there's a lot of work to do.

Robinson told you before almost anyone else that he knew he was going to retire, correct?

He used to play second base or third base.This particular day he was playing left field, and a ball went by him and rolled all the way to the fence and he missed it. We had dinner that night and he said, "You know Ronnie, if I had to do it all over again I probably wouldn't have played all the sports I did." And he said "I'm going to tell you a secret that no one else knows except my own family: I think next year is going to be my last in baseball."

When was the last time you spoke with Robinson?

I was with him about six months before he passed away. His health had been failing pretty badly. He had a heart attack, he had diabetes, he was blind in one eye and going blind in the other eye. I remember going into this restaurant in New York and we had to take two steps down into the restaurant. I had to take him by the arm and help him down those two steps. I felt so sad because I envisioned him dancing up and down the base paths and driving those pitchers crazy, and now I was helping him.

Afterwords, I hailed him a cab and I got him settled, and I leaned in and kissed him on the cheek and I told him how much I loved him. That was the last time I saw him. I remember as the cab pulled away, I just stood there. I realized that probably that would be the last time I would see him. I had tears running down my cheeks.

Jon Terbush is an associate editor at TheWeek.com covering politics, sports, and other things he finds interesting. He has previously written for Talking Points Memo, Raw Story, and Business Insider.

-

Moltbook: The AI-only social network

Moltbook: The AI-only social networkFeature Bots interact on Moltbook like humans use Reddit

-

Judge orders Washington slavery exhibit restored

Judge orders Washington slavery exhibit restoredSpeed Read The Trump administration took down displays about slavery at the President’s House Site in Philadelphia

-

Kurt Olsen: Trump’s ‘Stop the Steal’ lawyer playing a major White House role

Kurt Olsen: Trump’s ‘Stop the Steal’ lawyer playing a major White House roleIn the Spotlight Olsen reportedly has access to significant U.S. intelligence